Beyond FitzRandolph Gate, the hustle and bustle of Nassau Street — full of trendy restaurants, University apparel shops, and retail chains — serve as the facade of the town, the first image that tourists, visitors, and University students encounter upon leaving campus grounds. But unbeknownst to many non-residents, past Nassau lies a history of segregation and an ongoing struggle to preserve the culture of the town’s historically African-American Witherspoon-Jackson neighborhood, whose first inhabitants settled in the 1680s.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median Princeton property value in 2017 was $809,200, representing an increase of over 25 percent since 2010 and standing in stark contrast to the overall 11 percent decrease in median property values in the state of New Jersey. But this increasing prosperity of the town has come at an unsustainable cost to many lower-income residents, some whose families have lived in Witherspoon-Jackson — the houses and apartments spanning from Paul Robeson Place to Birch Avenue — for generations.

“We’ve had a lot of challenges recently dealing with affordability,” said councilman Dwaine Williamson, who has lived in Princeton for over two decades. “In a sense, it’s almost like we’re victims of our own success.”

Williamson pointed out that many Witherspoon-Jackson residents who are “multi-generational families, mainly African-American,” are suffering from the “ever-increasing demand to move in.”

Documented reports of black displacement from Witherspoon-Jackson go back almost half a century ago. In 1981, a New York Times article voiced concerns made by then-Princeton residents that the deaths of elderly black homeowners, increasing University influence, and high bids on properties made by wealthy — and primarily white — outsiders were, in large part, to blame for the “decline of [black residents by] 32 percent in Witherspoon-Jackson.”

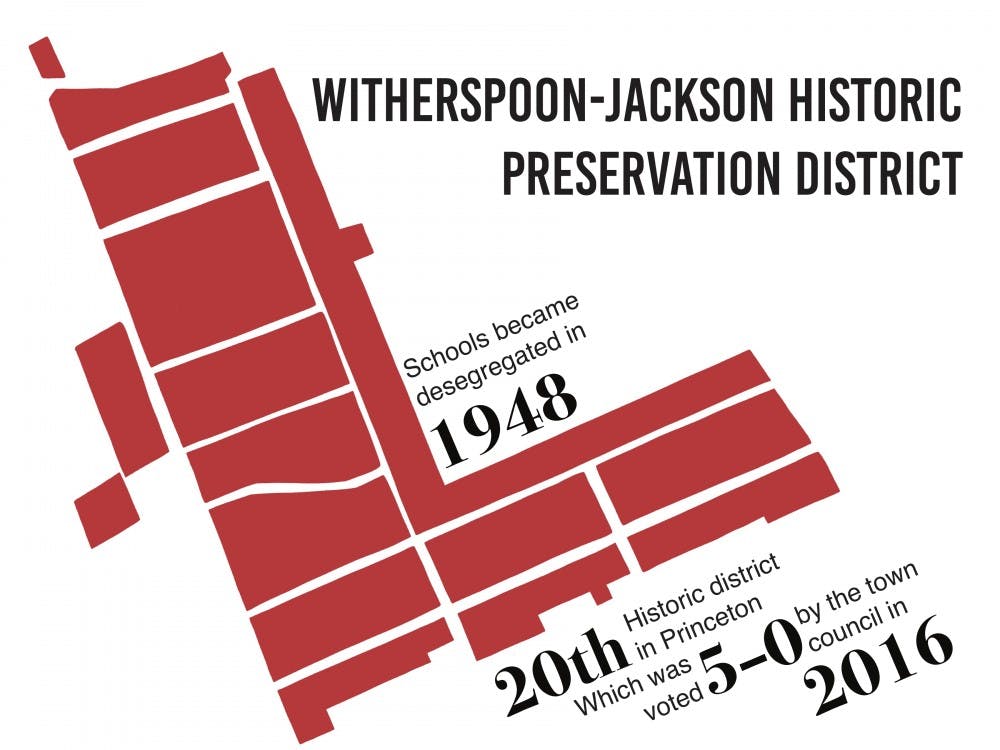

In an effort to preserve the historic aspect of the neighborhood, Witherspoon-Jackson was named the 20th historic district in Princeton in 2016. This decision came after nearly a year of debate among town residents and community leaders, including Williamson, who is a former municipal Planning Board member.

“It deserved to become a historic district to preserve the status quo, the neighborhood’s character,” Williamson said. “It also had the ancillary benefit of limiting what outsiders may want to do in order to change the neighborhood, especially because we are simultaneously having the scourge of tear-downs in Princeton.”

Councilwoman Leticia Fraga, councilman Tim Quinn, and former councilman Lance Liverman did not respond to request for comment by the time of publication.

Preserving the neighborhood’s architecture, history

But simply naming Witherspoon-Jackson a historic district did not end the neighborhood’s problems. As the town’s population continues to increase, questions have been raised about how to both sustain Witherspoon-Jackson’s history and culture and simultaneously provide enough housing for all of the town’s inhabitants.

In 2016, Studio Hillier, an architectural design firm located in the heart of Witherspoon-Jackson, released a report on the neighborhood and the firm’s future plans for it, noting the necessity of creating more housing units as well as designating more of them as affordable housing.

“As the price of the Princeton housing stock continues to increase, it is becoming harder and harder for the middle and working class populations to live within the community,” the report reads. “New innovative solutions for the provision of housing are necessary … like converting old buildings to housing developments, repurposing unused backyards, [and] allowing for micro-apartments.”

Studio Hillier co-principal and lifelong Princeton resident Bob Hillier ’59 GS ’61 explained the firm’s goal of renovating and restoring buildings in the neighborhood without excessively modifying their original appearances.

“Our intention is to restore these houses so that the historic aspect is a prettier picture than it is today,” Hillier said, emphasizing the need for stronger foundations, fixed plumbing, and increased energy efficiency in the houses.

In 2004, Hillier also took on the ambitious project of restoring the Witherspoon Street School for Colored Children, which had been one of the only schools in Princeton made available for African-American children from its creation in 1858 to its desegregation in 1948. Upon restoration, Hillier converted the building into the Waxwood, an apartment complex named in honor of Howard B. Waxwood, Jr., the school's African-American principal during desegregation.

According to Hillier, of the Waxwood’s 34 total apartments, eight are reserved as affordable housing units specifically for Witherspoon-Jackson residents of more than 10 years, or their direct descendants.

“People who have lived in the neighborhood and work here should be able to live here,” Hillier said.

Shirley Satterfield, who lives on Quarry Street and whose family has lived in the town for six generations, worked with Hillier to commemorate the racial history of the town, launching the Heritage Tour early in 2018.

The Heritage Tour focuses on 26 sites in Princeton that have been significant in its African-American history. Each site will eventually feature a plaque donated by community members to provide an explanation for the location’s importance in the town.

“The reason why I’m doing all this is to preserve and share and respect the heritage and history of the African-American community in Princeton,” Satterfield said. “Eventually, some of these places are not going to be here, but the plaques will be, so people will remember.”

Satterfield experienced the desegregation of schools in Princeton while growing up, but noted that the process to racial equality in the town has been long and ever-ongoing.

“Our community was basically neglected by people in Princeton, but our people took care of it,” Satterfield said. “I want people to know that this is where African Americans lived, and this is what African Americans did, and this is how they sustained the community, and not only the community, but the town of Princeton.”

From “Colored YMCA” to Paul Robeson Center for the Arts

While conversations about Witherspoon-Jackson often concern housing, the Arts Council of Princeton, housed in the Paul Robeson Center for the Arts, has stood by its mission of “building community through the arts” to “contribute significantly to economic development [and] promote cross-cultural understanding and appreciation” since its founding in 1967.

The arts center stands at the neighborhood’s southeast corner of Paul Robeson Place and Witherspoon Street. It occupies the building that was formerly the neighborhood’s “Colored YMCA,” described on the town’s website as the former “focal point of the Black community.”

In the last five years that she has worked at the arts center, Outreach Program Manager Barbara DiLorenzo has observed the steady replacement of older buildings in Princeton with significantly larger, more modern ones.

“Some of the old, run-down houses are getting knocked down, and the structures that go up look like they cost millions,” DiLorenzo said. “They look like whoever afforded the house that got knocked down in the first place could not have afforded [the new one].”

In spite of the landscape rapidly changing around the center, DiLorenzo noted that the continued diversity of Witherspoon-Jackson allows children “from all different backgrounds” and “families from all around the world” to take part in the center’s goals.

“I get to see kids grow up and embrace art in a way that, if you go to other places, other schools, other pockets of different cultures, art may not be as welcomed, or people may not have the idea that art is open to everyone,” DiLorenzo said. “One of my missions is to spread that word that we are all entitled to a creative life.”

Artistic Director Maria Evans, who has worked at the arts center for 20 years and lived on Leigh Avenue for the past 25, has witnessed drastic, long-term changes in the neighborhood over the decades.

“When I first moved there, probably all of my surrounding neighbors were African-American,” Evans said. “Now, I think there’s only two or three families on my block left.”

But despite this drastic change in the neighborhood’s demographics, Evans noted that the children who come to the arts center are still quite diverse.

“We still get kids from the neighborhood,” Evans said. “We get kids from all over.”

Evans also pointed out that the arts center has evolved with the times, just as the neighborhood has, but still attempts to preserve some of the original building’s integrity.

“While we were renovating, the very first design had a much bigger facade, but the architects went back to the drawing board and incorporated many elements of the old building to keep some of the original elements,” Evans said. “It’s a merging of new and old in this neighborhood.”

Growing up in Princeton

While all Princeton residents grapple with the lingering effects of segregation and the new consequences of gentrification, the town’s complex racial history has a very different effect on those who have spent their entire lives here.

Christine Jordan, who moved to Princeton in 1970 with her husband, University history professor William Jordan, noted the “varied experiences” that her four children had while attending Princeton schools.

“My husband is black, so my children are mixed,” Jordan said. “I think it was difficult for them in some ways growing up, and figuring out their identities was part of it.”

Jordan also noted that the racial demographics of the town, which is 73.2 percent white, played a role in her children’s relationships growing up.

“They did run into prejudice from time to time,” Jordan recalled. “In some cases, it kind of set them in a direction that has held for their lives, depending on how they handled it.”

Justin Hinson ’21 recalled his family moving to Witherspoon-Jackson seven years ago for “a more stable, financially comfortable situation,” forcing him to confront his “preconceptions and understandings that [he] had about the neighborhood.”

“It was understood by people in the general Princeton community to be a neighborhood of lower income, relative to the higher property prices in the rest of Princeton,” Hinson said. “It was certainly a diverse neighborhood, and it did carry a higher percentage of minorities, specifically African-American and Latinx people.”

Although the racial questions that Hinson encountered throughout his life in Princeton motivated him to become deeply involved with conversations about race at the University — such as through being a board member for the Order of Black Male Excellence and “connecting with [and] learning more about people with different backgrounds” — Hinson said that he continues to grapple with his own personal relationship with the town itself.

“Growing up here, being born here, I know that there are certain qualities about the town that have been shaped into my own personal identity,” Hinson noted. “I don’t want to deny those things or reject them just because of how I feel about the racial demographics in this town.”

Hinson hopes that, after graduation, he can continue to play a role in fostering conversation and dialogue in the town about its cultural diversity and rich history.

“It’ll always be a part of me, in a way, no matter how my future goes,” Hinson said.