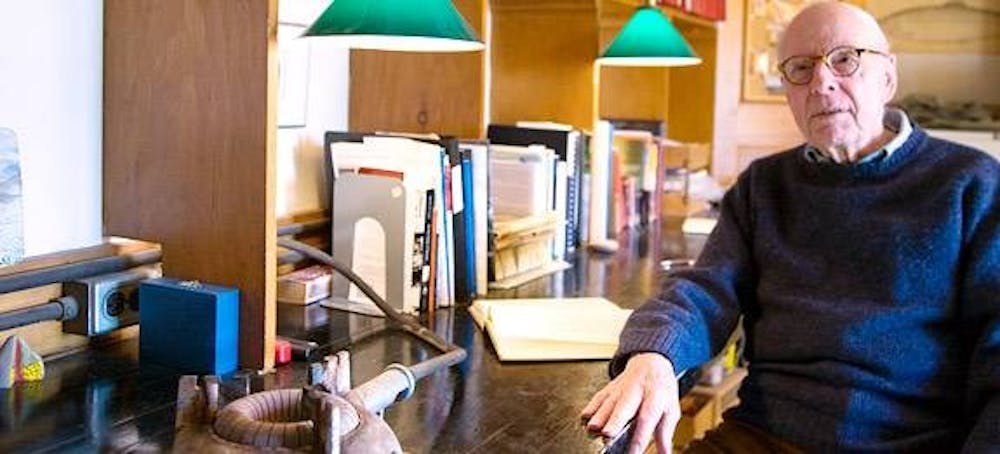

John Bonner, Professor Emeritus and pioneering expert on cellular slime molds, passed away on Feb. 7 at the age of 98 in Portland, Oregon.

Bonner was a member of the University faculty for 42 years and served three terms as chair of the Department of Biology.

He was known in the field for his work on slime molds, a class of soil-dwelling organisms that can exhibit unique collective behaviors. Bonner’s research on these protists, which he described as “no more than a bag of amoebae encased in a thin slime sheath,” was revolutionary at a time when few researchers were interested in the creatures.

Throughout his career, Bonner remained at the cutting edge of research on both molecular mechanisms and the evolutionary balance between the group and the individual.

“He touched on problems in both molecular biology and evolution that are right at the forefront today,” Henry Horn, Professor Emeritus said.

Bonner established the use of slime molds as a model system to test assumptions about evolution. One of his most important findings showed that even simple organisms like Dictyostelium discoideumum can be altruistic — able to benefit other organisms at a cost to themselves.

As a group, these cells travel in a “slug” formation. At some point, they form a fruiting body, with some cells forming the stalk and others releasing reproductive spores. The stalk cells, however, do not reproduce, sacrificing themselves for the sake of the live spores.

This finding shed new insight into how evolutionary cooperation takes place, said Professor in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Simon Levin.

“He was a pioneer. He did this work before anybody was thinking about these things,” Levin said.

Other colleagues agree that Bonner’s work continues to shape their research today.

“His early work on cooperation and self-sacrifice between different cell types provided insights that helped shape my work on balancing cooperation and competition,” Professor of Zoology and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Daniel Rubenstein wrote in an email to The Daily Princetonian.

Bonner was born on May 12, 1920. A native of New York City, he attended Phillips Exeter Academy and then earned a B.A., M.A., and a Ph.D. from Harvard University, completing his studies in 1947. Prior to earning his final degree, he served in the U.S. Army Air Force for four years.

Bonner began working on slime molds as an undergraduate in 1940 and continued this research when he joined the University as an assistant professor in 1947. He became the Moffett Professor of Biology in 1966 and transferred to emeritus status in 1990. In the decades after, however, Bonner would continue teaching, researching, and writing.

Slime molds fascinated Bonner for over 70 years. He studied their ability for chemotaxis, or movement in response to chemicals. He also studied how they moved together as a group and how they oriented towards gases.

Bonner authored 20 books and more than 160 papers on slime molds and beyond — one of which was accepted for publication in the last few months of his life and has yet to come out. Besides its impact on the field of evolutionary biology, his work has applications to issues ranging from environmentalism to biofilms.

His colleagues remember Bonner as not only a phenomenal researcher but an excellent friend.

“He was one of those rare individuals who combines being a great scientist and being a great human being,” Levin said.

David Wilcove met Bonner as a graduate student in the biology department in the early 1980s. Wilcove, now Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Public Affairs, remembers Bonner for his trenchant observations and insightfulness at faculty meetings.

“He exemplified the phrase ‘a scholar and a gentleman,’” Wilcove said. “He was unfailingly a light.”

Horn, who met Bonner when he joined the faculty as an assistant professor in 1966, went to Bonner for advice on lectures, research, and personal life.

“It was that wonderful accessibility he had,” Horn said, that made everyone from undergraduates to fellow professors comfortable around him.

Rubenstein also remembers turning to Bonner as a source of insightful advice on dealing with the constraints of working within organizations.

“His wise council helped me understand and cope with these challenging dynamics,” Rubenstein wrote in an email to the ‘Prince.’

Horn said that he will dearly miss Bonner’s way of connecting across disciplines, and his ability “to talk constructively with someone when you disagree entirely.”

“His willingness to discuss those bigger problems critically and constructively” with a combination of “rigor and charity” is what Horn said he will miss most.

Edward Cox, Professor of Biology, Emeritus, met Bonner when he began as an assistant professor in 1967.

Cox remembers Bonner as a champion of new faculty members and students just getting on their feet.

“He stood out as a supporter of young people, not just his undergraduate and graduate students, but especially his faith in young faculty,” Cox wrote in an email. “John’s ability to help and steady beginners was extraordinary.”