Malcolm X once said, “The most unprotected person in America is the black woman.”

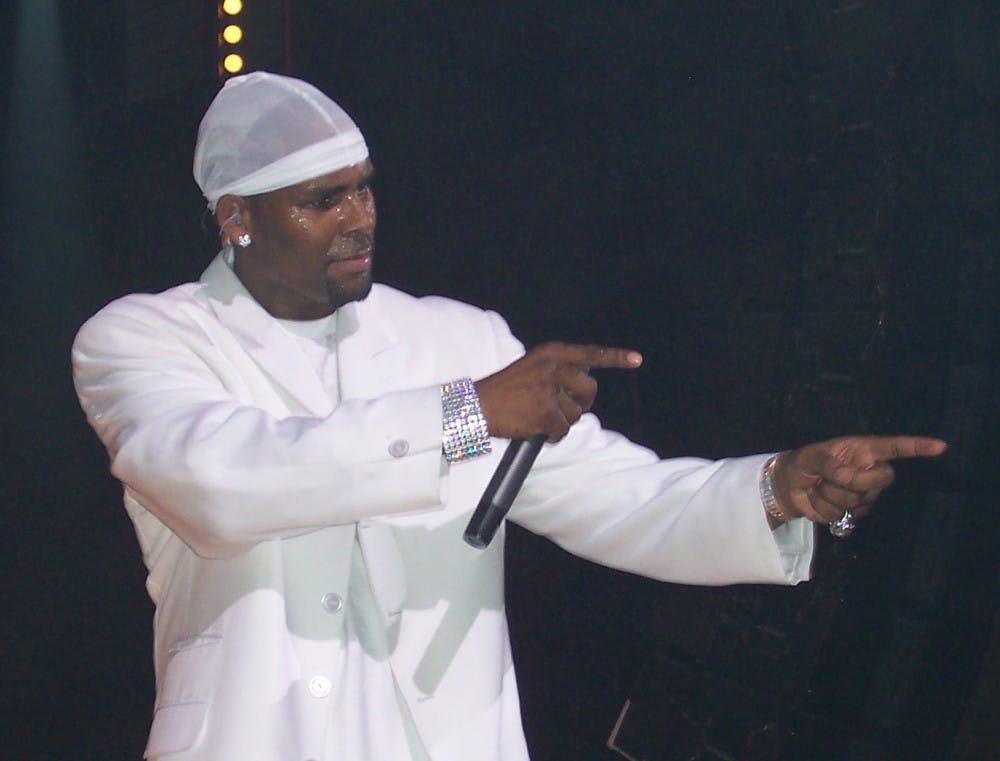

With Lifetime’s recent airing of “Surviving R. Kelly,” a docuseries that examines the cornucopia of sexual-violence accusations against the prominent R&B singer, America keeps proving Malcolm X right.

Kelly (who has, for the most part, denied any wrongdoing) is an alleged serial rapist and abuser; it seems most, if not all, of Kelly’s victims are black women and girls. If the accusations are true, Kelly appears to be a sexual predator at the level of Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, Ariel Castro, Larry Nassar, and Jerry Sandusky.

The allegations against Kelly, outlined recently by The New York Times, range from pedophilic rape to quasi-sexual slavery.

What makes these blood-curdling accusations even more sickening is the long-term complicity of the music industry in helping Kelly avoid accountability. The industry, as well as its fans (basically all of us), have looked the other way upon reports of Kelly’s abuse of young, sometimes underage, black women.

Interestingly, amid the ongoing #MuteRKelly movement led by black women looking to bring the musician to justice, Kelly has tried to complicate the racial narrative of the allegations: his camp has claimed that #MuteRKelly is an “attempted public lynching of a black man who has made extraordinary contributions to our culture.”

Of course, Kelly is not, in any way, experiencing the type of systemic white-supremacist terrorism that took the lives of Emmett Till, Martin Luther King Jr., Trayvon Martin, and countless other black men. If anything, Kelly’s self-victimization is just an attempt to confound the fact that black women have credibly accused him of sexual violence for decades.

Kelly’s disingenuous self-victimization not only reinforces American society’s disregard of black women’s trauma and suffering but also trivializes actual structural violence against black men.

Throughout American history, and to this very day, black men have been collectively and falsely painted as sexual predators — and themselves victimized by white-supremacist sexual assault. (In fact, R. Kelly himself has said he was sexually abused as a child.)

In the postbellum South, for example, many white women coerced black men into sex, threatening, ironically, to falsely accuse them of rape — which was culturally punishable by lynching — if they resisted the women’s advances.

And this atrocity correlated with the broader crisis of black men — throughout American history — being falsely accused of sexual predation, which thereby enabled a racist criminal justice system to sanction their incarceration or execution — sometimes extralegally, by a lynch mob — for crimes they didn’t commit.

Tragically, it seems that black men continue to be wrongfully convicted of rape and other violent crimes at disproportionately higher rates than their white counterparts.

Given the very real, unjust sexual criminalization of many black men in America, it’s a shame that someone like Kelly would exploit and distort this fact to serve his own interests and delegitimize, intimidate, and silence the black women he has harmed.

Unlike countless other black men, Kelly is not being publicly scorned because of his black-male sexuality but rather because he has used his fame and fortune to allegedly abuse black women for decades.

What’s more, the way in which Princeton students — and the University — address sexual misconduct seems to ignore the type of nuanced, often disregarded considerations embodied by the Kelly allegations.

Outside of Sexual Harassment/Assault Advising, Resources and Education (SHARE) events and educational programming, which are increasingly taking a more intersectional approach, discussions of sexual abuse at Princeton tend to be decontextualized from the racial realities of American life. (Full disclosure: I serve as a SHARE peer.)

The fact that women of color are more likely to be sexually assaulted goes nearly undiscussed in most social and intellectual spaces at Princeton.

Of course, all survivors of sexual assault, no matter their identity, deserve equal access to emotional, social, institutional, mental health, and legal resources, as well as empathy from fellow community members, to heal and find peace.

But it’s also important to address why women of color are overwhelmingly more likely to be violated than any other demographic — and to create more visible, accessible resources and social spaces on campus specifically for survivors from marginalized backgrounds.

Likewise, we should not be afraid to address the bigoted sexual hypercriminalization of black men in American culture, a culture that, of course, extends to college campuses.

Such discussions would provide spaces for men who feel dually marginalized by white supremacy as well as a white-centric feminism — which tends to disregard the experiences of sexually alienated men — to share their experiences. (Importantly, compared to white-centric feminism, intersectional black feminism does a much better job at addressing the complex relationship between race, gender, and sexuality.)

Adjacently, the Kelly accusations — and the broader erasure of the experiences of people of color, especially black women, who have been sexually harmed — reveal yet another ugly truth about white America’s hypocritical, amoral treatment of black people.

Needless to say, the white power structure in this country has often been profoundly eager to criminalize and incarcerate black men — except, curiously, when black men have been credibly accused of harming black women. Such white moral indifference is partly why Kelly has escaped scrutiny for his misconduct for so long.

Nonetheless, black women, despite enduring a wicked synthesis of racism, misogyny, and dehumanization from all corners of American life, continue to stand against a broad-based culture of sexual cruelty.

We should all, finally, stand with them.

Samuel Aftel is a junior from East Northport, N.Y. He can be reached at saftel@princeton.edu.