Three days after the 2016 presidential election, I watched a protest against President Donald Trump outside of Nassau Hall. People railed against the president-elect’s racism, misogyny, and conservatism. His heated rhetoric of Mexicans “bringing crime” and being “rapists” rocketed immigration to the forefront of national dialogue. After that day, there were rallies, op-eds, petitions, and clubs created to oppose his policies.

Since then, for the past two years, I’ve been cynically watching campus activism at the University and other schools. Students have become so reliant on blaming politicians for causing societal problems that they fail to see how their own communities can contribute to those same problems.

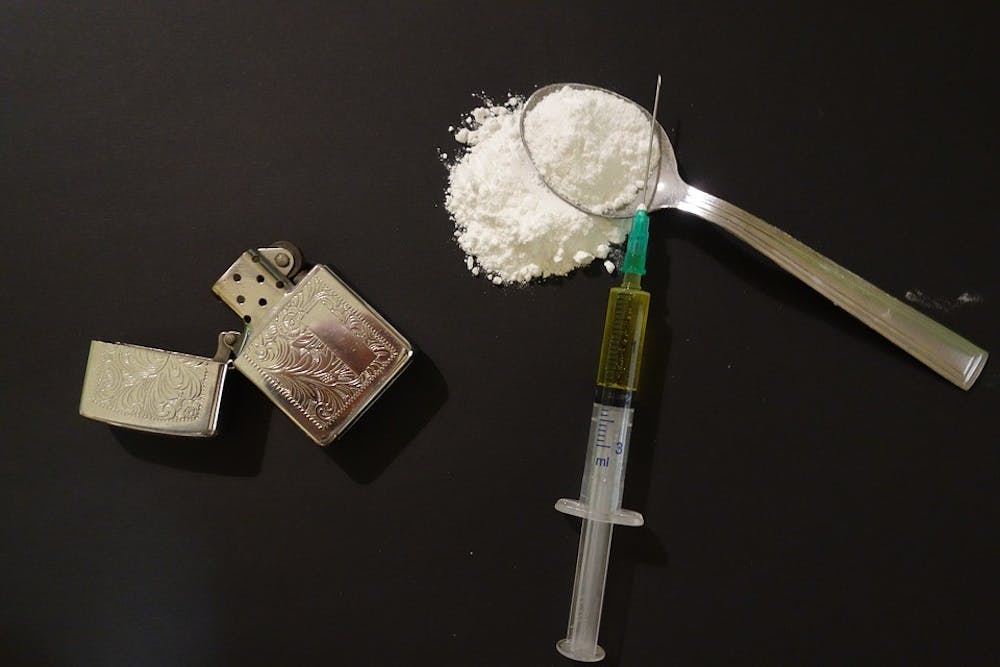

Drugs play a large role in worldwide oppression, but I’ve yet to hear this issue discussed on campus. Even more paradoxically, there are many students who call themselves “woke” (or consider themselves politically aware) and simultaneously use drugs.

Protests against Trump’s policies ignore what forces immigrants out of their home countries. A headline from a 2017 article in The New York Times aptly describes the problem: “U.S. Appetite for Mexico’s Drugs Fuels Illegal Immigration.”

Forty-two percent of people apprehended at the southern U.S. border in 2016 came from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador — three countries with some of the highest homicide rates in the world. Drug cartels don’t cause all of the violence in Latin America, but they do play a significant role in it.

White House Chief of Staff John Kelly told a Mexican official last year, “I acknowledged to my counterpart that America’s insatiable appetite for drugs is the cause of much of the turmoil on their side of the border.”

Over 200,000 people have died in Mexico’s drug wars since December 2006, and Colombia only recently emerged from the shambles of its own cocaine-funded conflict. Drug-related gun violence has claimed countless lives in U.S. cities. Abroad, powerful cartels bribe law enforcement and public officials with millions of dollars to ignore their crimes. Indeed, such violence helps spur immigration. But meanwhile, Americans continue to annually spend $100 billion on illicit drugs.

College students are at least partly to blame for these problems. They have popularized drug use since the 1960s and still largely drive the culture surrounding them. The National Institute on Drug Abuse found that drug use is most common in adults of ages 18–25, and cocaine use is highest among college students. A survey by LendEDU said that a quarter of college students spend most of their money on alcohol and drugs.

The University’s 2013 National College Health Assessment reported that 19 percent of students have used marijuana, and 17 percent have used other drugs. Although these numbers seem low, they mean that up to 900–1,000 University students have allegedly given money to criminal organizations. Ten states permit recreational marijuana, but they are sufficiently far from New Jersey that the vast majority of the weed used on campus probably doesn’t come from legal businesses.

These statistics fail to capture the quantity of drugs consumed and the money spent on them. University students primarily come from the upper middle class, and they likely have more disposable income to buy drugs than the average college student. A report by the United Kingdom’s Social Metrics Commission found that the middle class consumes more drugs than the lower class.

It’s incomprehensible that students turn a blind eye to this. Purchasing illegal drugs shouldn’t be socially acceptable.

There was outrage when the Trump administration separated families that illegally crossed the border. There was outrage when the men’s hockey team wore sombreros at a Cinco de Mayo party. But there’s no outrage when a prep school graduate buys Colombian cocaine.

While University students comfortably use drugs in their ivory castles and lavish mansions, someone in a different part of the world is suffering for their selfish decisions. Each additional drug transaction gives violent gangs money to corrupt public officials, to enlist youth in their work, and to buy bullets that kill innocent people.

If the University’s social justice activists want to maximize their work’s impact, they should protest in the eating clubs or wherever else students use illicit drugs.

Legalization is an often-cited solution to decreasing drug crime. Regardless of whether it would actually work, it’s not politically viable. A 2017 Huffington Post poll showed that Americans overwhelmingly don’t want to legalize any other drug beyond marijuana. Changing this mentality could take decades.

In the short term, the best way to lower violence south of the border — and to fight real oppression — is to simply stop buying the drugs that sustain it.

Liam O’Connor is a junior geosciences major from Wyoming, Del. He can be reached at lpo@princeton.edu.