In a lecture Wednesday discussing gender and sexual harassment, University of Oregon psychologist Jennifer J. Freyd noted that suppression or loss of memories from childhood is often a “survival skill” of abused dependents.

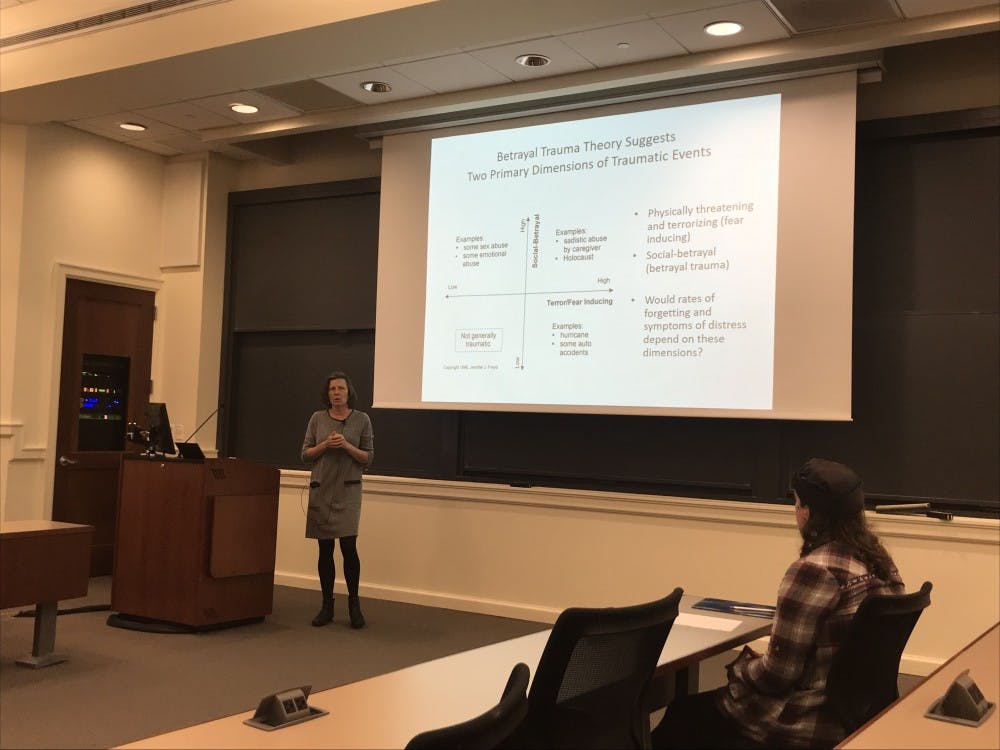

Freyd spoke to University students about her development of Betrayal Trauma Theory (BTT) and her research concerning how institutions, specifically university campuses, can reduce the trauma level of sexual abuse victims.

Freyd said she was inspired to understand how and why some individuals remain unaware of or forget traumatic memories after finding many of the existing answers unsatisfactory. For example, she argued that the theory that humans forget memories on account of extreme pain fails from an evolutionary standpoint, as retaining the memory could lead to a safer future.

According to Freyd, two concepts of human nature helped her to develop BTT.

First, humans are “highly sensitive to betrayal, because we are social creatures, and betrayal is costly to us,” Freyd noted. Subsequently, abuse, a type of betrayal, is very impactful in any level of relationship and provokes either a confront or withdraw reaction, she explained.

Second, Freyd said that humans are “extremely dependent on one another” and babies are the most dependent humans. As a result, people and babies have evolved to become attached to each other.

In the case that the parent takes on the role of betrayer, “the two systems collide with each other,” Freyd said.

The core idea of BTT is that if a child acknowledges and displays awareness of abuse by their caregiver, they are risking further mistreatment and endangering the entire attachment relationship — and thus their well-being.

“When a betrayal happens in a dependent relationship, there is now a survival advantage to not seeing the betrayal,” explained Freyd.

Freyd described how she was able to apply the idea of BTT to institutions. She posited that since humans refer to institutions with the same attachment terms they use with other humans, they would also be vulnerable to betrayal from institutions in the same way they are with humans.

An “institutional betrayal” could be either an egregious violation of trust or “the failure to do what [institutions] can reasonably be expected to do.”

In her research on campus sexual assault, Freyd found that, of individuals who had experienced sexual assault, those who also experienced institutional betrayal from universities — such as denial, lack of action, or lack of punishment — showed signs of higher trauma. “Institutional betrayal exacerbates anxiety, dissociation, sexual problems, and sexual-abuse related symptoms,” Freyd said.

Regarding the impact of gender on traumatic experiences, Freyd found that women were more susceptible to high-level trauma from interpersonal violence. Men tended to be more vulnerable to low-level trauma from relatively distant sources, such as accidents or strangers. She noted that gender does not affect an individual’s response to the an incident, but that women are more likely to experience high-level trauma.

Freyd ended by sharing her reports on sexual harassment on campus and recommendations for institutions to increase the likelihood that victims report incidents to authorities. For example, she recommended rewarding and cherishing whistleblowers for raising awareness of institutional issues and educating leaders on sexual violence and the consequences of institutional betrayal.

The lecture took place in Aaron Burr Hall at 6:30 p.m. on Wednesday, Nov. 7.