They crossed the border in search of refuge, and were welcomed and guided by the hands of the free and the brave. This is a reality someone might anticipate, based on the impression of our nation’s ideals. But for 28 undocumented single mothers and their children, who came from Central America, this was a fantasy. Upon entering Texas in 2015, these women and children were immediately deported without going before a judge. Although they petitioned for a proper hearing, a federal appeals court denied them this on the grounds that they were seized near the border.

Stories like the one above reveal that the talk on immigration policies is a much-needed conversation. With so many facets within this overarching topic, let us zoom into a specific point that will directly affect many undocumented immigrants currently in the United States. A law was passed that permitted the government to expediently deport undocumented immigrants. This deportation is done without the person going before a judge, on the grounds that they were not in the country for very long.

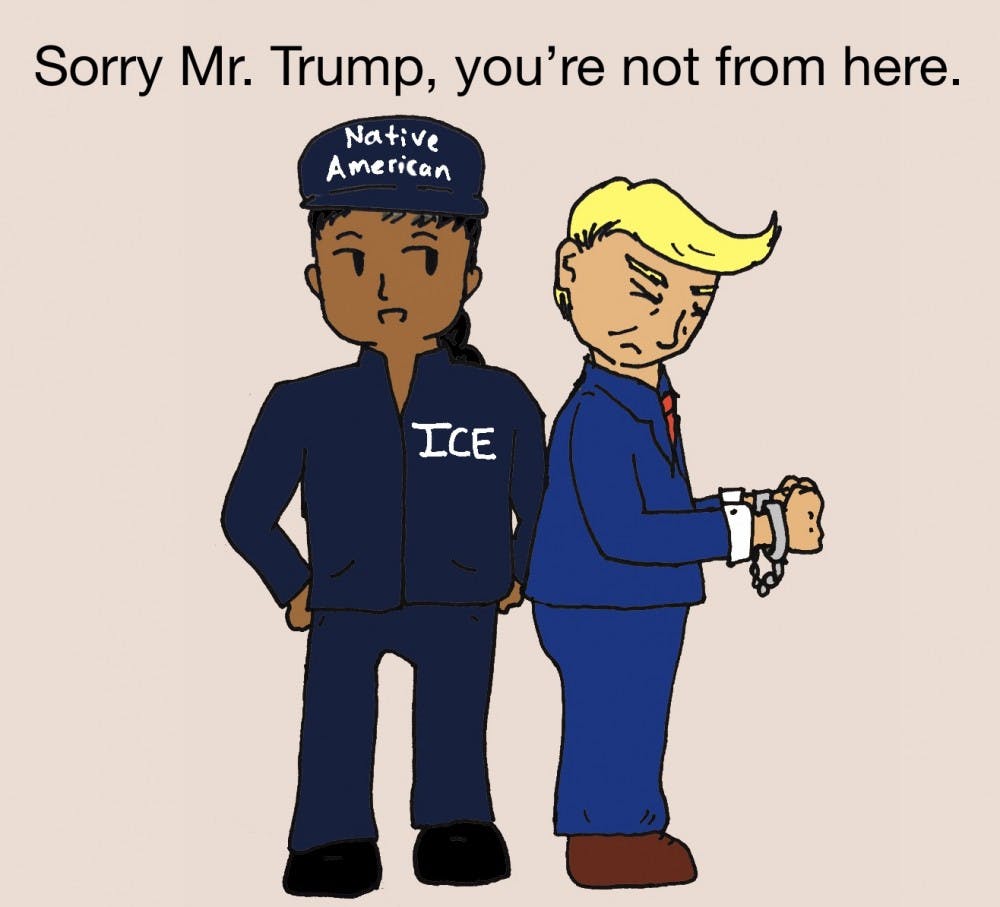

The “expedited removal” process applies to undocumented immigrants that are found to have been in the country for less than two years. Though it has previously only been used for people who were here for under two weeks and who were found close to the border, the Trump administration intends to utilize this process as a prime means of deportation, given that its procedure is time-effective and its impact pervasive. The Trump administration hopes to utilize the full potential of the law, specifically the two-year cut-off, lamenting the fact that the previous neglect or leniency in circumstance led to the accumulation of over 500,000 cases in immigration courts. In past years, the expedited removal process was not used extensively due to debates on its constitutionality under the due process clause. In accordance with this sentiment, the expedited removal process should be removed from law for its anti-humanitarian implications and unconstitutionality.

Lee Gelernt, deputy director of the American Civil Liberty Union Immigrants’ Rights Project, pointedly notes that a person who has been living for nearly two years amongst us in American society, in the northeast or otherwise, may be “swept off the street by an ICE [U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement] agent,” and not granted the decency of and right to a judge’s hearing.

This is incredibly inhumane. During two years of residency, people have already settled into their lifestyles, established friends, and forged ties within their communities. Then, all of sudden, they are stripped of a home and, worse yet, stripped of their rights.

While some may argue that an undocumented immigrant should not be granted the privilege of a judge’s hearing, the U.S. Constitution says otherwise. The 14th Amendment expressly states that “any person” may not be barred from “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” not just “any citizen,” thus including undocumented immigrants.

Moreover, the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution maintains that “no person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury,” confirming that a court’s hearing is necessary. Some may argue that cases of immigration are related to administrative law rather than criminal law, and therefore the courts need not get involved in order to carry out deportation. However, if a person is here on illegal terms, this is considered a criminal offense, and therefore they should be guaranteed a hearing.

Those who initially enter the United States legally, such as through a work or travel visa, and remain in the country past their restricted stay time are committing a civil rather than criminal violation. These cases rightfully earn immigration court proceedings. Such proceedings should be extended to those who enter the nation on undocumented terms.

It is unfair to put a timeline on someone’s life. The two-year term limit appears quite extensive, an umbrella over a great deal of people living in the United States. What makes a person living in the United States just one month short of two years any less credible and fit for U.S. residency than one who has lived here for a month beyond this threshold? The very fact that this law places time boundaries on one’s value in residency, yielding indecent treatment of the affected persons, reveals a fault line in legislation.

A law that questions a person’s deservingness of due process is a law that defies our nation’s ideals. Not only is it unconstitutional, but the expedited removal process is one that does not reflect a decent, humanitarian approach to immigration, and should be removed in an effort to attain a more comprehensive immigration reform policy.

Sabrina Sequeira is a first-year from Springfield, N.J. She can be reached at sgs4@princeton.edu.