When I first walked into the Class of 1970 Theater in Whitman, I was 15 minutes too early, and I thought I had stumbled onto a cult. The theater was tiny, less than 50 seats, and everyone was speaking Chinese. As I commented to a friend of mine, “I feel like I’ve been transported back to China.”

I felt like I’d been displaced, closed off from the real world. All that existed was the dark intimate space of this small theater. The night began with a trailer for the show, shown from a small screen in the corner. Scenes of death flashed by in fragments. A countdown announced both the elapsed time and the number of survivors left in the guest house. After 225 seconds, I was aware of a few things: The characters had gotten off a boat, they’d found their way into an empty mansion, they were being murdered one by one, and the murderer was someone among them. As someone who had never read “And Then There Were None” by Agatha Christie, I was paralyzed in my seat.

The program promised even those who had read the novel were promised that the play would end differently than the book, so all of us followed the plot like detectives, trying to figure out who U.N. Owen — the pseudonym of the “unknown” murderer — was and who would survive to the end (hint: no one).

The play, adapted and directed by Jianing Zhao ’20, found its niche in the treasure trove of student theater productions at Princeton that are of professional quality. “And Then There Were None” or “无人生还” gives attention to the smallest details to heighten the realism of the murder. Eerie music plays during silences and between acts. Lighting ranges from bright day to stormy candle-lit blackouts. We see Emily Brent, arguably the most put-together woman with disheveled hair as she devolves into madness at the hopelessness of her predicament. Dr. Armstrong is drenched in rain after the storm, sporting wet locks after a shower, or tugging at a damp collar nervously as he contemplates his own dark past, sweat from between his shoulder blades soaking through his sweater.

There is also an array of little Indian figurines on a stand stage left. Each time someone dies, one of these dolls crashes to the ground, ostensibly pushed over by a ghost. Later, Zhao told me that a member of the cast had designed a remote-controlled lever that knocked the doll off its stand. When Emily Brent dies, she remains upright in her seat, facing away from the audience, a stiff doll. She has been injected with potassium cyanide, but no one realizes it until a figurine crashes to the ground. Then, we are searching, searching, searching for the death.

Six become five, then four. The play slows down when only Dr. Armstrong, Judge Wargrave, Lombard, and Vera are left. Each has a moment in which he or she accuses another, forming a complicated ‘accusatory rectangle’ that mirrors the rectangle space of the room. Then, four become three. Two.

We arrive at the confrontation between lovers Lombard and Vera, who, realizing that they are the only ones left, accuse each other of being U.N. Owen. Lombard pulls a gun on Vera. She screams. They advance upstage, closer to the audience. Suddenly, they are in the audience. During the lovers’ fight, the boundaries between audience and actor dissipate. Vera, struck by her urge to survive, grabs the gun from Lombard,and shoots him. He falls, presumably dead, and Judge Wargrave runs in from the opposite aisle and reveals himself to be the true U.N. Owen. Wargrave is about to shoot Vera after a long monologue accusing the entire audience of being guilty — again blurring the boundary of stage and audience in true Tom Stoppard style — when Lombard, still alive because Vera is a terrible shot —raises his gun and shoots Wargrave in the head.

The denouement of the play is marked by the two lovers embracing and limping, Vera supporting the wounded Lombard, to the back of the stage, farthest from the audience, when they gaze out onto the ocean, depicted by a parting of the backstage curtain. The balcony created by the parted curtain enlarges the space of a theater I once thought tiny. In having the couple move from the back of the theatre, move through the audience, collapsing their plane of existence — and our plane of experience — into two meager dots, we are swept up, swallowed by the play.

I could tell the play had bled into my sphere of reality when at the climax, I could not stop laughing. Wargrave rages on madly and accuses the audience of unspoken sins, Vera whimpers loudly in the background, crying in terror, and I could not stop thinking, “The cape, that cartoonish cape that Wargrave wears … it is just too absurd.” My laughter was hysterical. The distress of the play had been creeping up to my throat, and I found myself looking for any way to escape.

In this play, laughter makes us terrified. Every time the audience laughs, we release some anxiety and free up space for the play to continue building suspense. Moments like Lombard snacking on Oreos or Dr. Armstrong rushing out in a bathrobe because someone stole the shower curtain, or even Wargrave shooting an audience member that fakes his death nobly — everyone laughs in these moments, but just like the characters in the play, we are trapped. Just as each character cannot leave the island, we are unable to tear our eyes away. And when Wargrave accuses us all of being guilty, we feel we are the ones who have lost the chance for redemption.

After the show, I interviewed Zhao. According to her bio in the program, Zhao drifted for four years in the Middle East and suffers from car/sea/air sickness but loves the feeling of disorientation. She occasionally dreams of being a mixologist, excavating ancient tombs in South America, or opening up a photography studio with her boyfriend in France.

This was your first time directing a play. Can you tell us the process of directing for the first time and challenges that you faced?

The biggest challenge I faced was resolving the discrepancy between artistic vision and the practicalities of carrying out that vision. Because I study literature, I’m used to reading a text, interpreting it, and forming a vision of it in my head. I was also a choreographer in high school, but directing a theater show is more complicated than choreography because the latter is more focused on bodily movement while with acting, there’s voice, movement, props, and an overall storyline.

This time around, I would say that the props were the most tricky part. Props are things you don’t think consciously about while you’re watching a show. You just kind of take them for granted. But when you’re actually designing the set, you have to think about, for example, how to place a table so that the audience will be able to see the actors’ faces. At first, we placed it horizontally, then we realized it was separating the audience from the couch. In the middle, it obstructed the view of the couch. But completely vertically some people would only see the actors’ seated backsides. So we put it diagonally, which is not a very realistic layout in the living room of a mansion, but you have to adapt certain things to the stage.

For this show, we know you were translating from a work of fiction to a theater production. Can you tell us about the process of adapting the original work of fiction? Were you translating from English to Chinese?

I wasn’t translating from English to Chinese because there are so many translations already out there from past adaptations of the original novel, but I read the English novel and spent much time cutting down the 10 original characters to six.

Agatha Christie writes in a very digressive style which works well for the novel — tangential conversations, false leads — but in the theatre you have to condense. A conversation that doesn’t actively contribute to the plot or character development easily distracts the audience and makes them lose interest. Adapting the play involved a lot of reorganizing of plot and dialogues, where the final product still had to flow smoothly and make sense.

And Whitman Theater is a small space. I can’t imagine 10 people all interacting on stage at once.

Yes, every interaction has to have purpose. The more characters there are, the more tangential moments there are. Cutting 10 characters to six limits digressions and gives each character more time to develop dynamically.

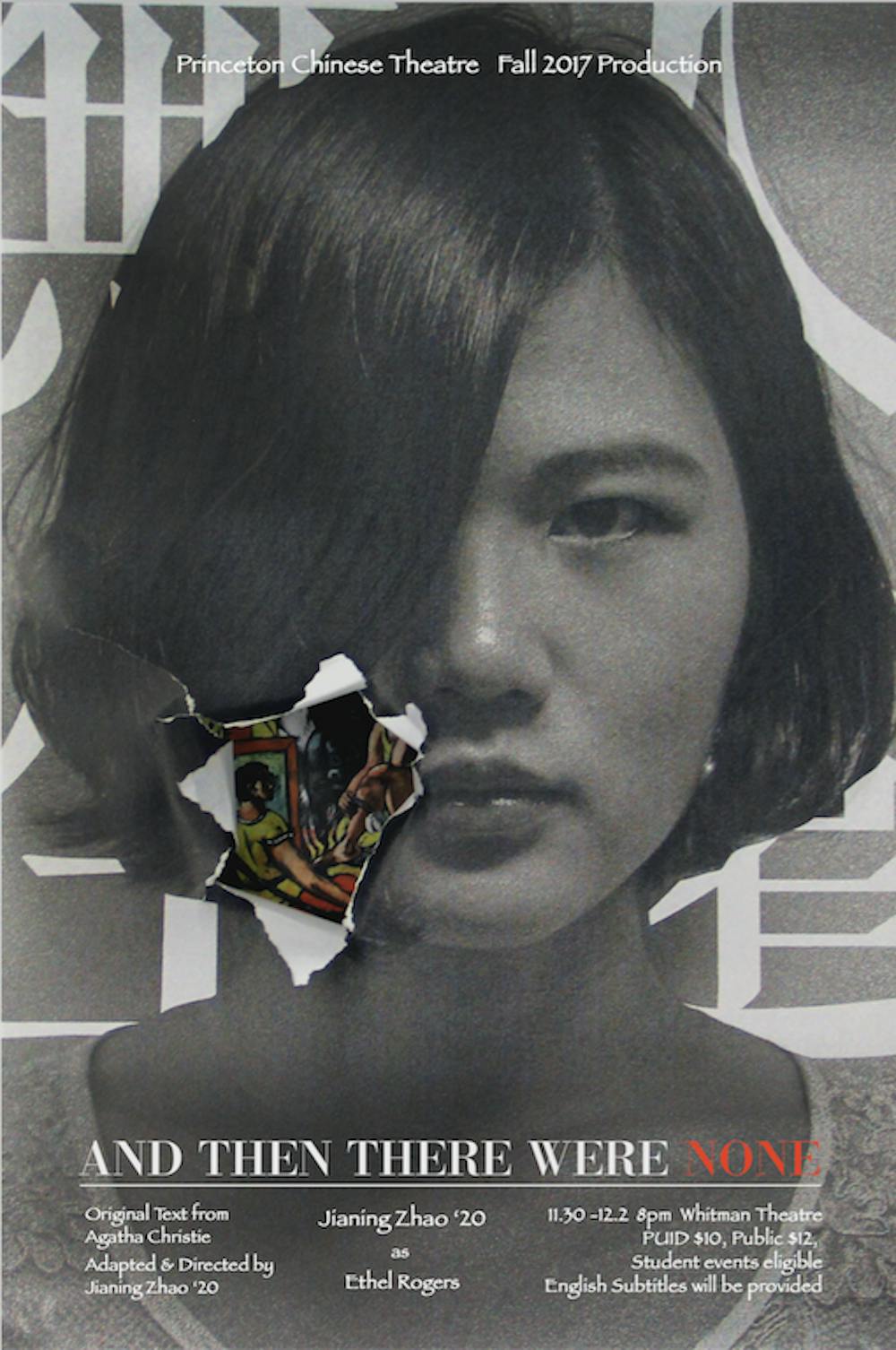

Additionally, there is a consistent theme of two-sidedness in each character that ends up showing through whether you have six or 10 characters. Each character has concealed a dark, murderous past and found ways to suppress his or her experiences. These dark sides are revealed through the course of the play. If you look at our posters, you see black and white photographs that are partially torn, revealing chaotic images underneath. I wanted to show that underneath an utterly civilized facade, there is always a darker side.

You were very deliberate in creating this “accusatory rectangle” toward the end of the show, where each character in turn was accused of being the murderer U.N. Owen.

Yes, the accusatory rectangle moment would have been difficult with the 10 characters because having too many accusations flying around chaotically would be hard to visualize and less powerful. I try to throw suspicion onto each character throughout the play.

In the first act, Ethel acts with animosity towards all the rich people that she has to serve, making her a murder suspect because of her vindictiveness, but then she dies.

In the second act, Emily is an ultra-religious woman that hates young people. She acts suspiciously when she refuses to deny her murderous past. Her conversations with Vera make … her seem like a cold-hearted killer. But, then she dies.

At the beginning of Act 3, where the accusatory rectangle happens, I’m trying to create this rectangle of suspicion within a rectangular space, between the four characters left. I wanted to play with the idea of space throughout this play. The space of enclosure — condensed into a rectangle on stage, a circle on the poster, a line invading the audience's dimension and eventually a dot — is not a backdrop for this murder mystery but a constant participant and a mirror of the characters’ psyche.

Indeed, each confrontation emerges naturally as a result of plot developments. Can you tell us about the ending? In the Agatha Christie version, Wargrave kills everyone in the guest house and later confesses it on a sheet of paper. Here, though, he is killed by Lombard. Lombard then reunites with Vera, but he ends up shooting Vera, and then shooting himself.

A lot of the audience came knowing the plot of the original text, so I wanted to do a version that was not a repetition of the book. The charm of a murder mystery lies in the uncertainty, in the fact that you don’t know what will happen next. The ending started with 10 seconds of seagulls as the couple looked out to the sea...

And then they realize there’s no boat and they’re not leaving the island.

Yes, there were 10 seconds of silence when the two gazed at the sea, with sounds of seagull circling in the background. I initially conceived it as a reference to Chekhov's play “The Seagull” which also ends with a tragic suicide, but probably no one would pick up on that [laughing]. We did no more than 10 seconds so that people wouldn’t start clapping. The seagulls also gave a false sense of peace — maybe, just maybe, this would end happily ever after — but the seagulls, with their freedom to fly and escape from the island, remind the audience that the young couple is trapped with no boat in sight and no way out.

And the final scene before blackout features Vera lying flat on the ground and Lombard standing straight above her, holding the gun to his head: a vertical line that is about to collapse upon the horizontal, a cross that denies any possibilities of salvation. Then blackout. One last gunshot. A sort of double erasure.

And there is this sense that Lombard is enacting a sort of justice. He and Vera couldn’t go on as if they were innocent. They had each killed someone.

It would be naive for the two to end up together. Their relationship started with flirtation and lust. As the plot progressed, they bonded out of the dire circumstances, but these bonds were precarious. It’s not like “The Hunger Games.” I was thinking about a happy-ever-after “Hunger Games” version, but the contestants in “Hunger Games,” at least Katniss, know what they’re going to face and even make the conscious choice to face it. Here, Vera and Lombard are thrown into this situation and forced to face their unspeakable pasts. After Lombard pointed his gun at Vera and Vera shot Lombard, there's no going back, and no way out.

Speaking of the couple, Vera’s character was really well done. The actress, Michelle, really fit the role. There was that one moment when Ms. Brent dies, but the audience doesn’t know it yet (because she remains upright sitting in the chair, facing away from the audience), but then Vera bursts out reciting the death of the 3rd Indian in the poem with hysterical laughter. How much did you write the characters according to the actors?

I wrote the adaptation before we cast roles, but we worked on that scene a lot. In order to get an accurate feel, the whole cast watched 10 Youtube videos featuring insane laughter and then practiced. It was fun.

We wanted to figure out exactly what kind of hysteria Vera was undergoing. Under extremely tense moments, people will break into laughter. But what kind of laughter is this?

Also, I was considering Vera’s physical relationship with Lombard at this moment. He reaches over to comfort her. She simultaneously rejects his physical comfort by pushing him away and accepts his comfort by clinging to him in a sort of bipolar way.

It represents the ambiguity of their relationship.

Yes, the very instinctive human desire for protection and connection and its futility.