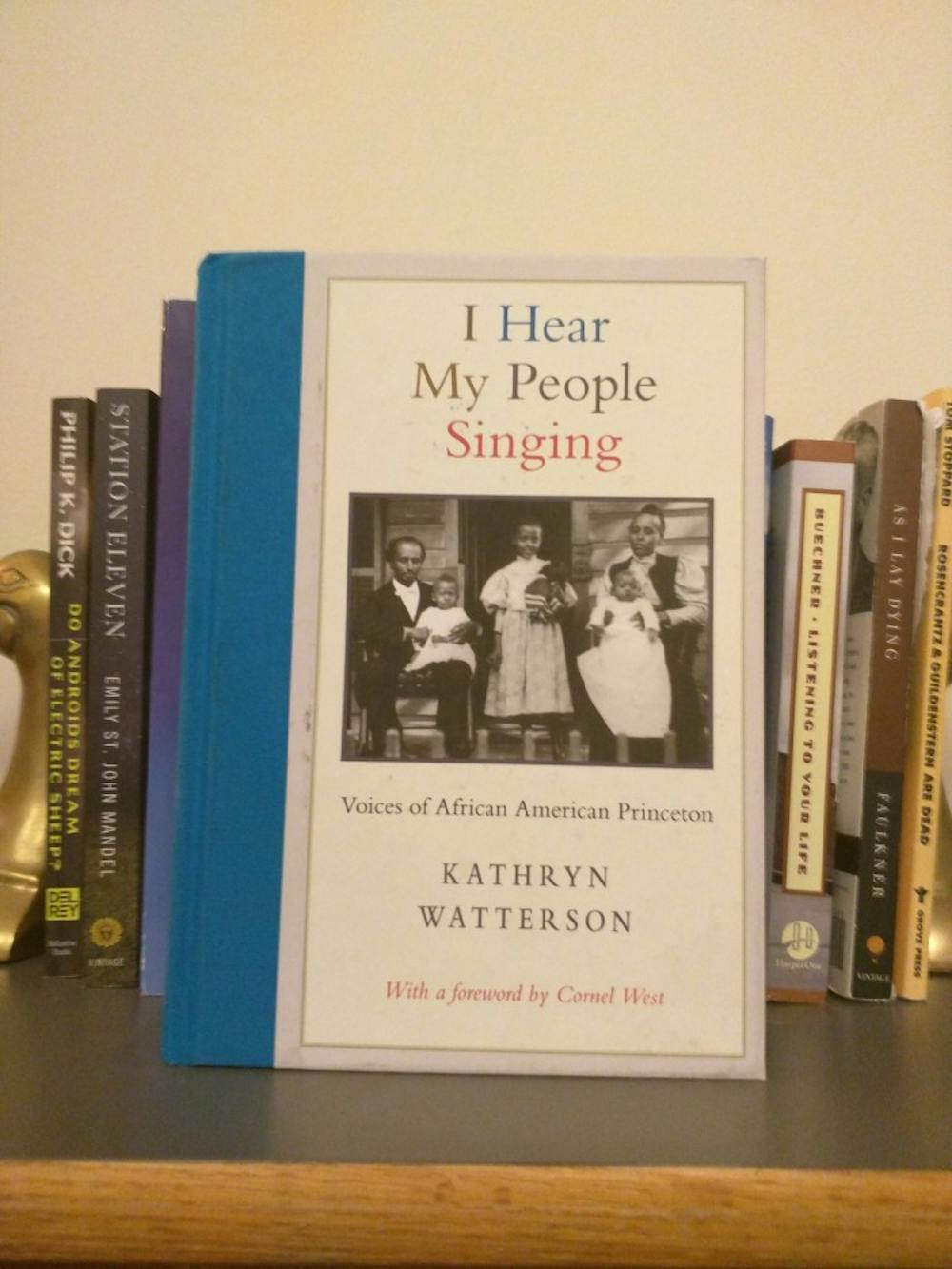

During the course of the Princeton Slavery Project, several important works about African Americans were examined and discussed. In one of these works, I Hear My People Singing, former University Professor Kathryn Watterson writes about the lives and experiences of the African American community just outside FitzRandolph Gate.

Watterson, a writer and professor of Creative Writing at the University of Pennsylvania, collaborated with residents of the Witherspoon-Jackson neighborhood, as well as several former University undergraduates, to create the book outlining the oral history of the community.

“Our intention for this book was to bring the historic Witherspoon neighborhood into view and to share the sweep of its rich history,” Watterson writes in her introduction. “An unplanned result of the process is that the wealth of individuals’ life stories has provided a fresh lens for illuminating the persistence of racism’s harsh realities.”

The majority of the book consists of excerpts from the interviews done in the early 2000s, with Witherspoon residents telling their stories and the stories of their families. Although Watterson herself conducted many interviews, most were conducted by University undergraduate students and members of the Classes of 2001, 2002, 2003, and 2004, allowing them a better view of the world directly outside of the “Orange Bubble.”

“I felt exhilarated as I watched my students discover for themselves the humanity I’d been experiencing from my black friends and mentors since the 1960s and 70s,” Watterson added in her introduction. “I loved seeing the students tearing off the blinders, and moment by moment being given unexpected insight into the false notions of race and racial superiority.”

Watterson focuses on specific issues, challenges, and aspects of residents’ lives from chapter to chapter, ranging from integration of schools to how the University itself affected them. In writing the book, she seeks not only to tell the community’s history, but also to celebrate their humanity.

“Kathryn Watterson…has performed a monumental service in laying bare the rich humanity of black Princetonians in this magnificent and marvelous book,” University professor emeritus Cornel West GS '80 writes in his foreword to the book. “We all owe her an enormous debt for her courage, vision, and love.”

Within their respective interviews, the older residents of the Witherspoon community tell the stories of their fathers and grandfathers moving from the South and slavery, as well as their own stories living in what Watterson consistently calls, “The North’s Most Southern Town.” For a long time in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, African American community members could only sit in the back of the movie theater, could not go to certain restaurants, and could not shop at the stores on Nassau Street.

“It was the same story all over New Jersey, in bars, bowling alleys, diners, places to live” novelist James Baldwin wrote in his essay collection Notes of a Native Son, which Watterson cites in her book. “I was always being forced to leave, silently, or with mutual imprecations.” Baldwin worked at a defense plant near Princeton in the 1940s.

Despite the prolific racism and segregation of the time, the stories of the Witherspoon community are also stories of hope. Residents remember their childhoods with fondness, constantly talking about how “everybody knew everybody”, and sharing the love of the place they called, and many still call, home.

“The children all played together, white and black” Floyd Campbell, Princeton resident and World War II veteran, described in the book. “We had our fights and problems, but we had them as children would be [when] confronted with problems. They were not about race. Those problems were between our parents.”

Ultimately, I Hear My People Singing presents the deep-rooted racism that did and still does exist in America. The focus, however, is always on the people. Watterson presents the Witherspoon community and its residents as vital to Princeton’s past history and present story today.

“I told you, you got to read our history. They had to make the jobs. We had to work – any kind of work you could find. We built this country! We built it!” Johnnie Dennis said in the book. Dennis moved to Princeton on his own when he was thirteen and became a permanent Witherspoon resident. “It just wasn’t built by white men. It was built up by everybody.”