Princeton’s exclusivity is old news, and it seems as if it’s embedded in the University culture. For at least two decades, Princeton has not accepted undergraduate transfer students. Today, Princeton is the only Ivy League school that does not. It keeps us exclusive, once again.

But, according to the University’s Strategic Framework for 2016, “the board [of Trustees] authorized the reinstatement of a small transfer admissions program.” This is radical. Accepting transfers would mean that Princeton would allow students to apply to enter the University as undergraduate second- or third-year students, rather than first-years.

The framework is taciturn on the details of the transfer program other than to say that, “Experience at other universities shows that transfer programs can provide a vehicle to attract students with diverse backgrounds and experiences, such as qualified military veterans and students from low-income backgrounds, including some who might begin their careers at community colleges.”

Transfer students have not been admitted to Princeton since 1990. The plan cites student body diversity and expansion as the motivation for the restoration of the program. This decision is part of a broader initiative in the Strategic Framework to increase the undergraduate student body by 125 students per class, or 500 total. There is no specific timeline for reinstitution, as the plan just says, “for 2018.”

Last year, the Editorial Board made recommendations for a small transfer program, including admitting transfer students to boost diversity, improve athletic teams, and be as competitive a pool as regular admission.

Princeton needs to take this reinstatement step gingerly. The Board’s recommendations for reinstatement offer a lot of opportunity to reinforce exclusivity at Princeton.

University administration needs to look beyond these recommendations and look to its neighbor institutions for guidance. Other elite schools with transfer programs should serve as learning material for Princeton. The way the program is implemented will decide where the apple will fall: will Princeton further its culture of exclusivity? Or will it follow through with its promise of diversity?

The way that Princeton defines “diversity” here does not match the word’s typical connotation. From the context in the strategic plan, diversity describes students who could not choose a private university as a high school senior, typically due to financial reasons. This would allow those who chose a military institution — which are typically “free” with five years of service — or an affordable community college the opportunity to re-apply to private institutions from a more financially stable position, or, alternatively, to receive more attention and consideration than they may have received in regular application.

The other Ivy League schools have admirable programs for transfer students. Each has a unique policy from which Princeton can learn from.

Yale has Transfer Student Counselors, or “TroCos,” who are students who transferred to Yale previously and are “designed to help incoming transfer students adjust to life at Yale and explore the full realm of their interests.”

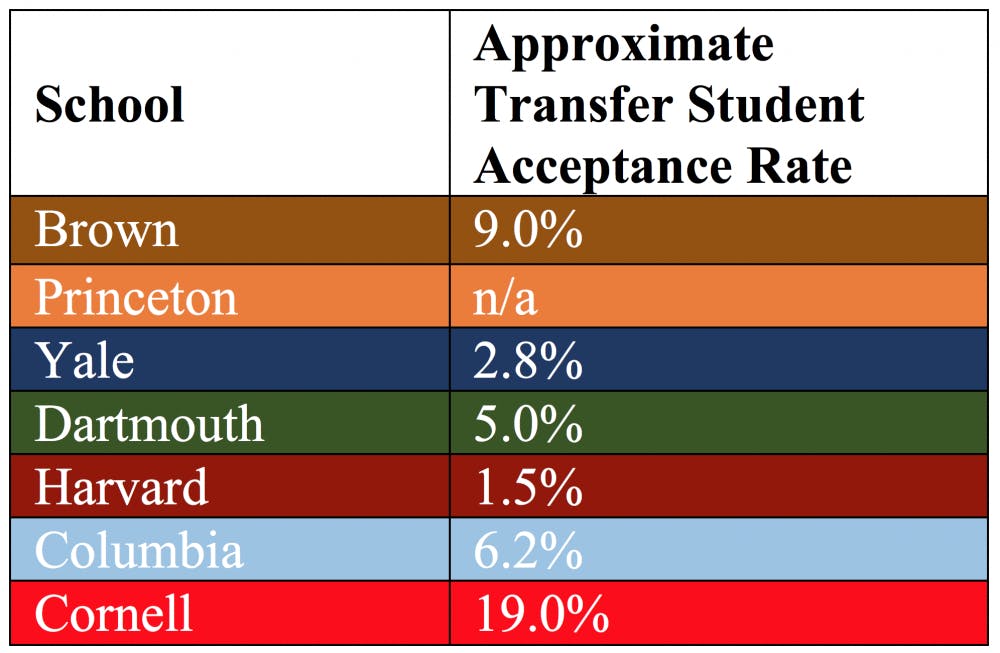

In a typical year, Yale accepts 20 to 30 transfer students out of approximately 1,000 applicants, making for a 2–3 percent acceptance rate. But acceptance rate isn’t a good yardstick for inclusivity, because each school has a different undergraduate population, a different amount of student housing, and a different capacity of students that it is able to enroll. These varying factors are quantified by the range of transfer student acceptance rates among Ivy League schools.

Source: The College Matchmaker

With the second lowest acceptance rate, Yale is candid about the fact that they “must deny admission to most qualified applicants.” They also have a statement remarkably similar to the one in the Strategic Framework, saying, “diversity within the student body is important, and the Admissions Committee works to select a class of contributing individuals from as broad a range of backgrounds as possible.”

Of the 18 Yale TroCos for this year, there are only three who previously attended a two-year college or military academy before enrolling at Yale. The other 15 students are from well-established four-year institutions, either private or public, with most being of similar caliber to Yale.

Undoubtedly, from reading their bios, these TroCos are unique and come from a range of diverse backgrounds. Unlike Princeton, Yale makes no statement directly referencing community colleges and military background as transfer student assets. However, I think given its statement in the Strategic Framework, Princeton has the opportunity to have a higher ratio of students from two-year and military institutions. These applicants are currently outliers at the University, but could become common on campus if the transfer program made them a priority.

At Cornell, transfers are welcomed with open arms, no matter why they are transferring and no matter the place from where they are transferring. Cornell’s transfer student acceptance rate is higher than the regular applicant acceptance rate; approximately 650 transfer students join the Cornell campus each year.

The first female graduate of Cornell was a transfer student and transferring has been part of Cornell since its founding. According to Cornell’s admissions website, “whatever the reason, Cornell University welcomes transfer students to a degree unmatched in the Ivy League.” Unlike Brown or Yale, Cornell makes no commitment to background diversity in transfer admissions.

Princeton could learn from the high acceptance rate. Although the number of applications makes this difficult to control, to the maximum of the campus’ capacity, the admissions committee should admit as many qualified applicants as possible. Give as many students as possible the opportunity for an elite education, and deprioritize the notoriously low acceptance rate that already exists for regular applicants.

Brown has a column on its undergraduate student blog, entitled “Second Time Around,” where two female transfer students reflect and share their experiences as transfer students, with articles as simple — yet, significant — as “Brown abbv’ns + A.C.R.O.N.Y.M.S.” to more pragmatic comments on “Getting Involved on Campus.”

The blog references the higher transfer acceptance rate of 100–200 students per year. Although Brown has a higher acceptance rate than all the other Ivies besides Cornell, its transfer application program is “need-aware.” Unlike “need-blind,” this means that your financial situation is taken into account when they consider your admission. “Need-aware” is typically seen as discriminatory towards applicants from lower-income backgrounds, in that applying for financial aid may weaken their application.

This isn’t a judgment of Brown for being “need-aware” — that’s Brown’s decision, and I respect it. It’s not cheap to admit 200 students on full financial aid. However, I think that Princeton can find it within the 22 billion dollar endowment to be need-blind and accept students purely based on merit and diversity.

This is no critique of the systems at Yale, Cornell, and Brown. Rather, it’s information that Princeton can learn from. Princeton has the distinction of going last. We can observe, learn, emulate, and evaluate the programs around us as we re-mold our own transfer program. This is Princeton’s opportunity to break out of its stereotyped exclusivity — the Princeton transfer program has the potential to be revolutionarily inclusive.

Here’s hoping the apple falls far from the tree. Here’s hoping the inclusivity of our transfer bites at the exclusivity that exists on campus.

Although we may not be able to control the acceptance rate due to finite amounts of campus resources and possibly infinite numbers of applications, there are other aspects of transfer admission that we can, and should, control to meet the vague criteria that the plan outlines. Selecting diverse students from institutions unlike Princeton and making the admission process “need-blind” is certainly a start.

If this apple falls far from the tree, then maybe its seed will inspire a whole new tree entirely: a tree of inclusivity.

Emily Erdos is a sophomore studying Sociology from Harvard, Mass. and be contacted at eerdos@princeton.edu.