Japanese internment camps existed because of prejudice, hysteria, and failures in leadership, former World War II detainee Sam Mihara argued at a lecture on Monday.

A San Francisco native, Mihara was first taken to a temporary camp in Pomona, Calif. He then was moved to the Heart Mountain camp, which spanned Cody and Powell in Wyoming. After the war ended three years later, he was released and then attended high school. He graduated with a bachelor's degree in engineering from UC Berkeley and a graduate engineering degree from UCLA. He built a career as a rocket scientist at the Boeing Company before retiring.

He traced the cause of the removal of Japanese people to the late 1800s, when many Japanese and Chinese workers came across the Pacific Ocean to build railroads in the U.S. as the Great Expansion occurred.

Mihara noted that in the 1940s, President Franklin Roosevelt signed an executive order giving local military commanders the authority to move people. On the East Coast, General Hugh Drum chose not to relocate German and Italian families. On the West Coast, General John DeWitt pledged to remove anyone with one-sixteenth Japanese blood.

Mihara jabbed at the promise within the Pledge of Allegiance of “liberty and justice for all.”

“We were denied liberty, because we were removed from our homes,” Mihara said. “We were denied justice, because there was none; not even a hearing.”

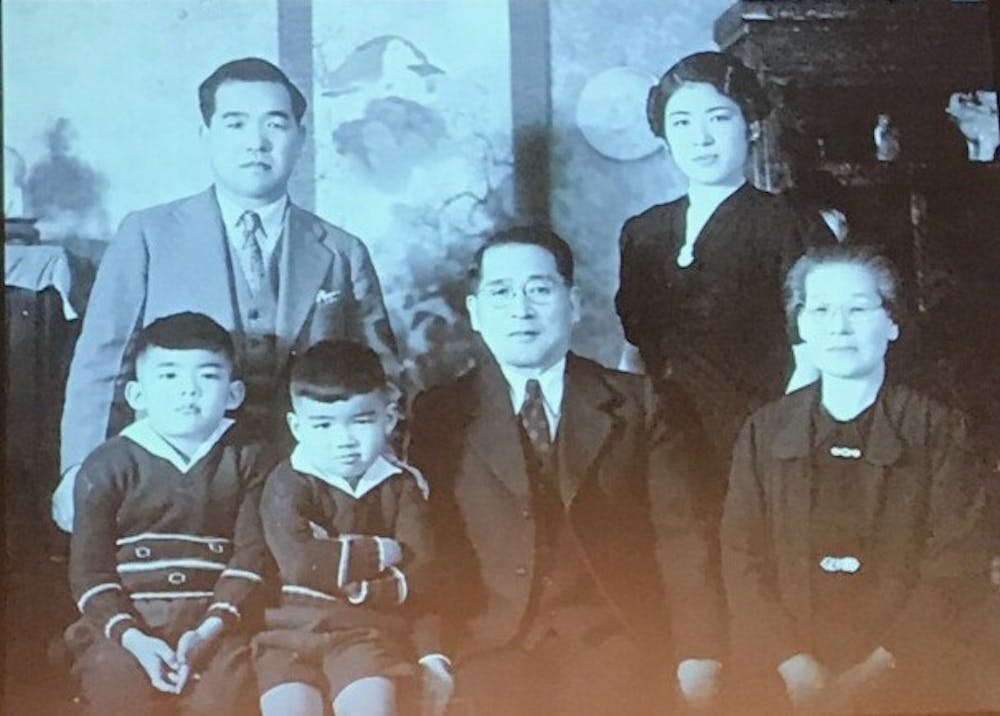

After gathering the addresses of Japanese Americans from community registries, the government sent Mihara and his family to Heart Mountain, which was initially a set of horserace tracks modified with fences. Detainees lived first in horse stalls, then in hastily constructed shacks.

The government began to build a high school within the camp. However, when local townspeople protested that since they were not receiving new schools, neither should prisoners, the internees had to finish the project themselves.

Mihara described unpleasant camp conditions, including bad food in the mess halls and toilets without partitions allotted to every 600 people. His father became blind. His grandfather developed fatal colon cancer. Ignorant guards had been treating his grandfather with a laxative, Mihara later learned from medical records.

Mihara noted that he still remembers his cell number, containing his block and barrack, as well as his prisoner number.

Heart Mountain qualified as a prison because of its guard tower, floodlights, and, most importantly, signs in English and Japanese that threatened harm to anyone who tried to exit the fenced area, according to Mihara.

“If anybody inside these camps feels they're going to get hurt by crossing the border, they are in a prison,” he said. “That condition made us prisoners of the U.S. government.”

Of 120,000 Japanese Americans, only three resisted internment. The welder Fred Korematsu, after being fired by the government because of his precarious position, decided with his white girlfriend that he would spend all his money on plastic surgery intended to make him appear white, so that he could avoid detainment. However, an employer caught him and reported his actual ethnicity, and he consequently was jailed. The Supreme Court ruled against Korematsu, citing the danger from espionage. It also upheld the convictions of Gordon Hirabayashi, imprisoned for walking outside past curfew, and Minoru Yasui, a lawyer who asked a police officer to arrest him so that he could prove internment was unjust.

When Mihara and his family returned home, local people shunned them through signs and other means. Some former internees committed suicide. In one case, a man unable to find employment killed himself so his wife and children could then survive on his life insurance payment.

“The idea of mass imprisonment without justice continues to live,” Mihara said, listing hostile reactions to certain groups after the Cuban missile crisis, 9/11, and other incidents. But he reminded all those who see mass imprisonment as the solution to imagine their own families as victims: “I simply say, 'Never again to anybody, not to anybody at all.’ ”

Titled “Memories of Heart Mountain,” the lecture was sponsored by the Asian American Student Association. It took place on Feb. 20 at 4:30 p.m. in McCormick 101.