On Jan. 27, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that limited the entry of any refugee awaiting resettlement in the U.S for 120 days. According to the Department of Homeland Security, “For the next 90 days, nearly all travelers, except U.S. citizens, traveling on passports from Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Iran, Somalia, Libya, and Yemen will be temporarily suspended from entry to the United States.”

In line with the theme of ‘Hometowns,’ The Street interviewed students Maryam Bahrani ’19 and Neamah Hussein ’17 about their hometowns of Shiraz, Iran and Hodeidah, Yemen, and what being from those countries means to them.

Maryam Bahrani ’19

Daily Prince: Paint a portrait of Shiraz, Iran. What is it like? What is it known for?

Maryam Bahrani: I’m from Shiraz, which is a city near the south of Iran. The population is slightly under two million. It’s this city that was home to of a lot of poets and gardens. One of my friends from Tehran says that Shiraz is the Paris of Iran — the romantic area. Walking around the city in the spring, you can smell orange blossoms, there are these paths covered with trees.

DP: What does being from Iran mean to you?

MB: I never lived in areas where there weren’t a lot of Iranians. People warned me, “You might not be treated well.” I knew stories of people who would hide where they were from, but I never felt like that. I was always so proud, and I would always seek opportunities to talk about it, to speak Persian. I’m so in love with the language, Persian poetry. What does Iran mean to me? Its home, and it will always be home no matter where I will be.

DP: What do you miss the most about your hometown?

MB: One thing I miss most about home is four seasons. It’s never two weeks of spring, a humid summer, and it’s all gone. You feel every season. You smell spring, you see the fall, and I haven’t seen such stark contrasts since being here. I miss how warm and accepting everyone is, you feel the hospitality just by walking around the city. If you visit as a tourist, people will come to you, talk to you, invite you to their houses, to meals out. If you sit on a bus, everyone will talk to you — as opposed to here when you look down and stick to your own place. This concept of personal space is very different. I also spend a lot of time in Tehran as well. I stay with friends, we hang out, go on road trips. I love Tehran so much; it’s so lively at all hours, all the time.

DP: You mentioned being in Tehran, the capital of Iran. Do you have any favorite stories about Tehran that you could share?

MB: When I arrived this past summer, my friends picked me up. It was late at night. We went on a car ride, driving around. There’s an area that looks over the whole city; it’s a really nice place to look down on. Sitting up there, it’s kind of relaxing — which is kind of ironic, because it’s a hectic city, but being up there it looks peaceful. Also, because of a lot of the sanctions against the country, the Apple store wasn’t selling any of their products, so there was a big void in the country. What happened was that people rushed in to fill in those gaps, since there was a lot of need. There were so many start-ups, there was Iranian Uber and Iranian everything. My friends have started working there. Everyone I talked to had ideas. This lobby in a university in Iran was full of these little cubicles, it was kind of like a silicon valley culture — it made me think, “I want to be part of this, I want to contribute.”

DP: What do you want people to know about Iran?

MB: For me coming in to the U.S, Iran was home, but I had to form the stereotype of Iran by compiling all the questions I got. I was as amazed by the questions I got, as people were to know the answers. There were people who asked, “Are you from a war torn area?,” “Did you feel oppressed?,” “Do you have elections?” I would tell them, “I’ve never seen a war, and I’ve never seen a gun in my life, we can vote at sixteen years old.”

It’s home. There are many things wrong with it, and my generation specifically doesn’t agree with most of the things that go on in the government and we want to change it, but at the same time, there is this huge aspect of people’s lives that are unaffected by the government. The government is there, but it’s not the people. I would want every Iranian to be viewed as another person, before anything else.

Neamah Hussein ’17

DP: What is your relationship to Yemen?

Neamah Hussein: I am Yemeni by nationality. It is the only citizenship that I hold. I was born there. I lived there with my mother and my grandparents until I was four years old. My family had a perfume business that my grandfather was running. My mother was a dentist there. My grandmother used to work in Yemen as well. My mother’s side of the family has a long history in Yemen. I grew up in the family home there, with my grandparents and my mom. It was right above the perfume factory that my grandfather had, so that was quite a unique experience. I grew up around packaging and perfume and smelling all these wonderful different Arabic oils and learning about the different musks.

My family is now settled in the United Arab Emirates. My grandfather and my uncle identified that there were more opportunities for education and business in the UAE, more so than Yemen. So we moved there when I was about four years old.

DP: What are your favorite childhood memories of growing up in Yemen?

NH: Fairly regularly in my childhood, I would go with my grandmother to the perfume shop; I would go behind the counter. I felt very privileged to be a person who could go behind a counter in a shop. I would talk to all the workers there, a lot of them would go out and buy me chocolate every once in awhile and give me a piece of candy whenever I was there — it’s sweet little memories like that, where I grew up the adults around me. I didn’t have any siblings at the time, so for me, all my friends were adults who worked with my grandparents and my mother.

DP: Since moving to the UAE how did you stay connected to your Yemeni culture?

NH: When we moved to the UAE, Yemeni culture was always alive at home in the little things. For example, there’s this frankincense that we burn at home for good aroma. That is something that is always present in our house. That particular scent — as soon as I catch a whiff of that, it sends me back to the middle of the bustling streets of Yemen in my grandfather’s shop.

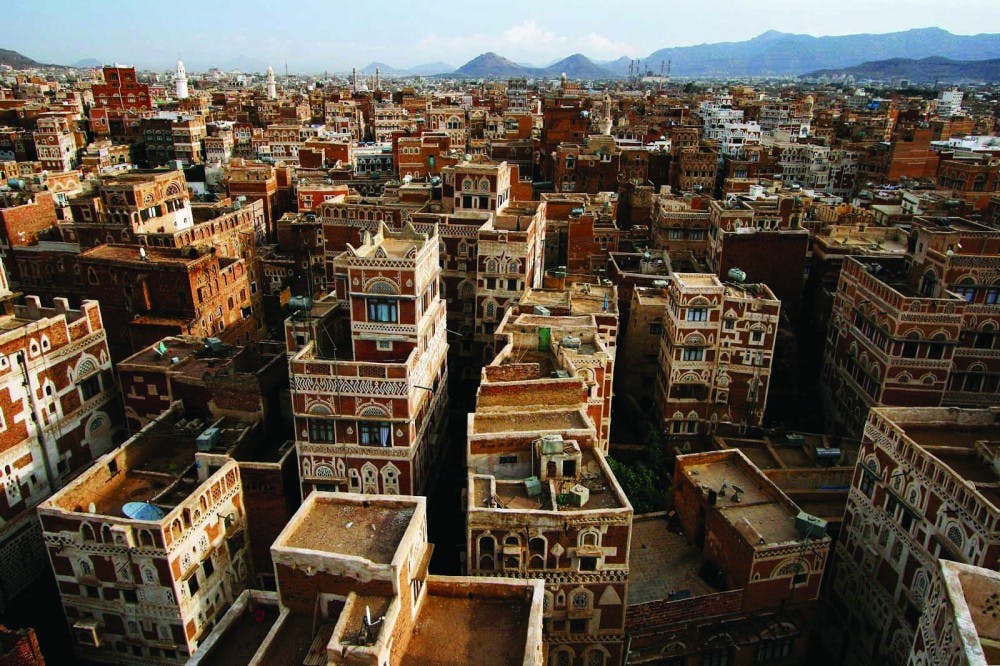

DP: In light of current events, how do you view Yemen now?

NH: Right now, I think of it and it hurts my heart to realize that I won’t be going back to the same Yemen that I left behind. It hurts to talk to people about their childhood countries, their childhood hometowns, and all the wonderful memories they have there and to know that a lot of people can go back to where they come from knowing that it is exactly the way they left it. It’s very sad that I don’t think I’ll be able to do that, with the state that the country is in right now. I have a cousin who still lives there, and she had to move cities because of the civil war that is going on right now. It’s unfortunate that everyone from generations who saw Yemen in its heyday, when it was so beautiful and wonderful to live there — it’s just sad that it’s no longer there, that it’s just an echo of a Yemen that used to exist in the past.

DP: What do you miss the most about Yemen?

NH: There are things that I miss even more, now that I’m not in the UAE anymore either, being even more removed from the Arab culture. I miss the sense of having this huge family around — whether or not you’re blood related doesn’t really matter. It’s just people around you who are constantly checking in and being very neighborly, and people who know you when walking down the street — I miss that.

DP: What do you want people to know about Yemen?

NH: It’s a beautiful country that’s unfortunately going through a very, very rough time. I just hope that people get to see what it was like in the past, sometime in the future.