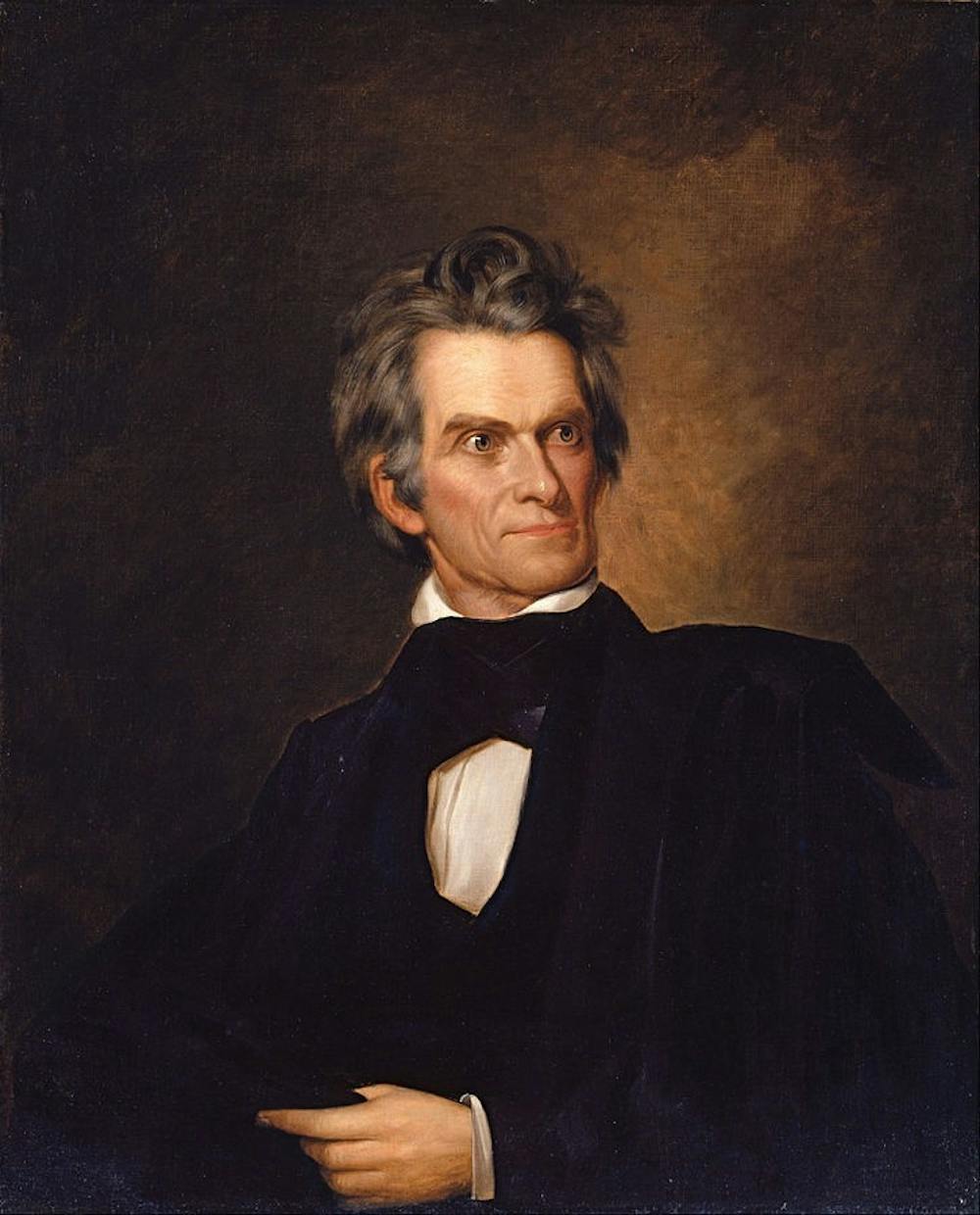

Last week, I defended the legacy of John C. Calhoun after Yale renamed its Calhoun College. But the two-term vice president from South Carolina is only the latest target in a larger war waged on college campuses. From Columbia University to Georgetown University, from Clemson University to Winthrop University, and even right here at Princeton, students are protesting men on the “wrong” side of history — thereby threatening our historical empathy and, in turn, our education.

We must remember that the winners write history and cast themselves as the “good guys.” As a result, we blindly loathe the losers without reexamining the actions and characters of the victors.

Take a look at the debate surrounding Calhoun. We abhor him for his defense of slavery while celebrating Henry Clay and Daniel Webster — his rival senators in the “Great Triumvirate” — for their abolitionism. But while Clay and Webster are considered to be on the "right" side of history, they had imperfections too. Clay promoted the westward expansion that led to the genocide of the Native Americans; Webster was an elitist who cared little for the average citizen.

Woodrow Wilson, Class of 1879, is another example. For many years, he was considered to be on the “right” side of history because of his progressive agenda. But as the Black Justice League correctly highlighted, he held racist views as well. Their protests showed exactly how our comprehension of history is warped by the victors.

The views of these leaders are unacceptable by today's moral standards. But we need to understand why they did what they did. Those who fail to learn from history, after all, are doomed to repeat it. We could see the rise of white supremacists again in the future if we fail to learn from our history — and even be disgusted by it — on a daily basis.

We will not “correct” history by removing these leaders’ names from buildings. Instead, we should use these markers to teach the public everything about them: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Keeping their names does not have to mean that we are celebrating them, either, but merely shedding light on their complicated legacies. By frequently remembering the flawed people and periods of the past on both sides of history, we become ever more committed to preventing our society from relapsing.

Further, removing names from buildings has the potential to threaten a university's funding. Think of our Frist Campus Center, which is named for the philanthropic Frist family of Tennessee. One prominent member of the family is Senator William Frist, Sr. ’74, who served as the Senate majority leader from 2003 to 2007. During his tenure, he fought for legislation that would have prohibited same-sex marriage.

According to Gallup polls, 55 percent of Americans believed that same-sex marriage “should not be valid” when these laws were first proposed in 2004. Thirteen years ago, there was a vigorous national debate about marriage equality. The pro-same-sex marriage faction eventually won with the Supreme Court's decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, and public support for same-sex marriage spiked. It will likely continue to rise in the coming decades. One day, LGBTQIA students may protest the Frist Center's namesake for his views.

But demonizing Senator Frist and removing his family's name — for being on what we will consider the “wrong” side of history — would have serious consequences. Private universities like Princeton and Yale depend upon affluent donors. Wealthy conservative alumni will shy away from donating to their alma mater if their names are not guaranteed to remain on buildings due to protests from the more liberal college students.

My critics may chastise universities for being at the mercy of the rich or construe my argument to claim that I value money over morals. But universities need donations to operate. Nearly everything at Princeton, from engineering research funds to the Center for African American Studies, relies on large contributions from alumni.

Princeton needs money to maintain its high quality of education for students of all backgrounds, and it cannot afford to cherry pick its donations based upon the giver’s political affiliation. Neither Wilson nor Calhoun donated to their universities, but expunging their names sets a precedent that endangers higher education's funding.

When evaluating our collective American history, we must realize that, as President Abraham Lincoln said, “There are few things wholly evil, or wholly good.” Both sides of history have their faults when we view them with our morals from the present. Even the “right” side of history — whether that be the abolitionists or anti-war protesters — is rarely perfect.

We can learn from our imperfect history, but only if we understand it. Renaming buildings with morally contemptible namesakes will create the illusion that the histories of our school and country were perfect. We might never have known about Calhoun and Wilson’s racism had their names not been on college campuses. Our posterity must know about our nation’s dark past. These names reveal it for all to see.

Liam O'Connor is a freshman from Wyoming, Del. He can be reached at lpo@princeton.edu.