Seven nationally recognized playwrights will create plays about the history of slavery at the University, which will premiere with the launch of the Princeton and Slavery Project on Nov. 18, 2017.

The Princeton and Slavery Project consists of research conducted by Princeton and Slavery Project Director and History professor Martha Sandweiss, University Archivist Daniel Linke, undergraduates, and graduate students. The project grew out of Sandweiss's seminar HIS 402 / AAS 402 / AMS 412: Princeton and Slavery, which has been offered multiple times since debuting in spring 2013.

“We've found richer stories than I anticipated or knew that we would be able to find,” Sandweiss said. “The really exciting part of the project now is that, unlike some other schools, we're not just conceiving of this as a narrow academic project, but as a collaboration working with local organizations to reach broader and more diverse groups with the history that we're uncovering,”

A partnership with the McCarter Theatre Center will bring the material to the stage in the form of multiple ten-minute plays by Nathan Alan Davis, Jackie Sibblies Drury, Dipika Guha, Regina Taylor, Kwame Kwei-Armah, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins '06, and McCarter Artistic Director and Resident Playwright Emily Mann.

Linke described the partnership as unprecedented in the 15 years that he has held his position. He added that it is the first partnership to integrate so many components. The University Art Museum will commission a display, the Princeton public schools will feature a related curriculum, the Princeton Public Library will organize programming, and the Lewis Center for the Arts will incorporate materials in classes, according to Linke and Sandweiss.

Though other schools have researched their relationships to slavery, notably Brown University in the early 2000s and Columbia University early this year, the Princeton and Slavery Project is distinctive in building community ties so as to explore the topic through more creative venues, Sandweiss said.

Theater represents a natural vehicle for the project, she added.

“Good history and good drama both try to make a reader or a viewer empathize with other people and situations that transpired that they couldn't experience for themselves, things that happened in the past,” she said. “But we're dealing with events that happened a long time ago, and there are so many silences in the archives. Playwrights have the freedom to explore those silences in ways that historians can't.”

Sandweiss said she first pitched the idea about a year ago to Mann. Instantly interested, Mann and the rest of the artistic staff at McCarter commissioned a variety of artists they admired, according to McCarter Literary Director Emilia LaPenta, who is overseeing McCarter's side of the partnership.

They sought original contributors who explore political themes and engage with current or historical events, LaPenta said. To guarantee the representation of different perspectives, they wanted multiple playwrights, with the number seven arising from budget considerations.

Every playwright that McCarter invited said yes immediately, a fact that speaks to the importance and timeliness of the project, LaPenta said.

Telling the University's history in full requires discussing how it related to and benefited from slavery, noted Linke, who facilitated HIS 402 from the start by bringing relevant materials from the University's archives to the classroom.

“If you really want to understand the whole story of Princeton, you need to understand this piece of who founded, supported, and taught at the institution, and how those attitudes played out, and also to understand that within the greater context that what's happening at Princeton is part of a national narrative,” Linke said.

He added that the University's official history, written in 1946, does not mention slavery. Expecting the project to yield few findings given the scarcity of surviving documents from the 18th and 19th centuries, he was surprised that new questions about old materials readily revealed answers.

Unlike Georgetown University or the University of Virginia, the University as an institution never owned slaves. But administrators, faculty, and students benefited from owning slaves. Those individuals then used their wealth or position to benefit the University, Linke explained.

Examples of slaveowners include donor Nathaniel FitzRandolph and the father of the University's tenth president, John Maclean Jr. Class of 1816. FitzRandolph Gate and the Maclean House bear their names.

“The first nine presidents of Princeton all, at some point in their life, owned people,” Linke said. “How does that affect the institution and how it views and teaches and inculcates its students?”

Furthermore, the University served as the ideological home of the American Colonization Society, founded in the 1810s to gradually emancipate slaves, but resettle all freed men in Liberia. University men, unlike those at Harvard and Yale, proliferated the ranks of the society nationally and in Southern chapters. “This movement served as an intellectual cover for people who didn't want to see change come to the institution of slavery,” Linke noted.

He added that the material on any particular slave related to the University varies from robust to sparse. The project unearthed many details about Betsey Stockton, whose owner, a University president, released her early. She used her literacy to serve as a missionary in Hawaii, and then returned to settle in Princeton. On the other end of the spectrum, slaves who were unable to write left only their names in the historical record.

“Princeton has always been seen as an august institution. What was it like to be a person on the fringes of that?” Linke said, expressing hope that the playwrights will exercise their imaginations to humanize the experience of slaves.

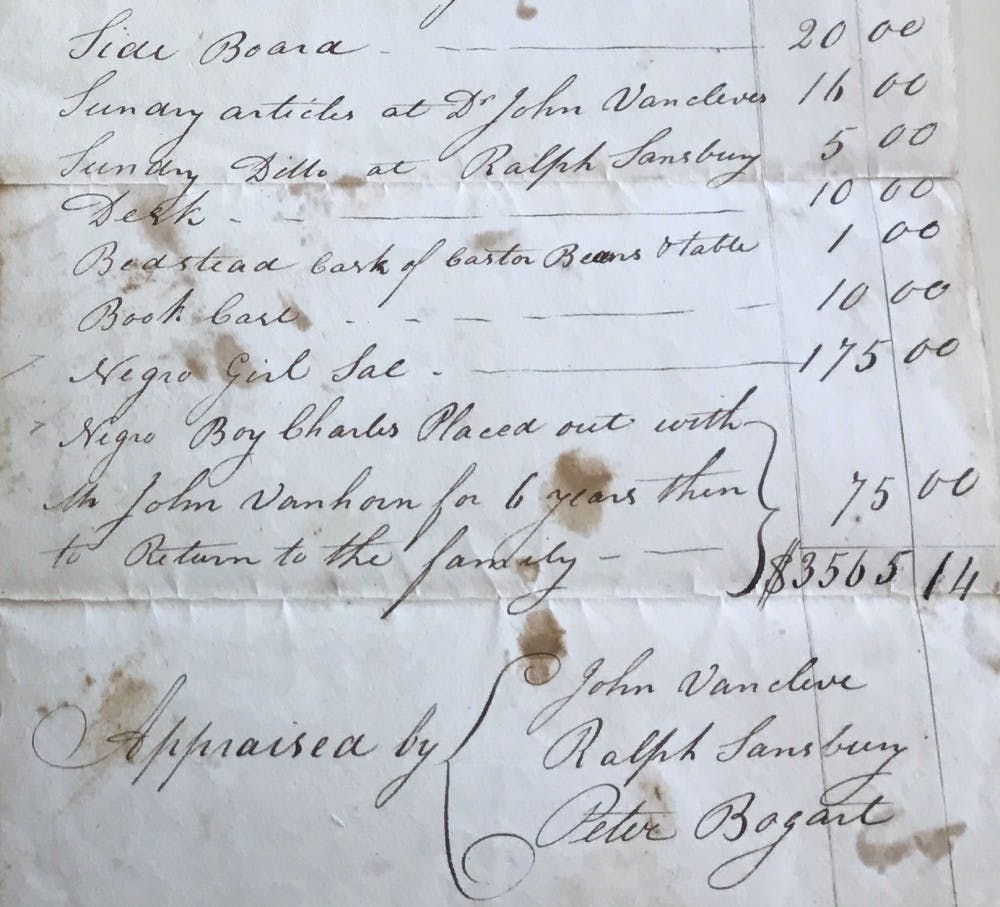

Sandweiss said she would like the playwrights to base their narratives on the documents, which include newspaper ads, sermons, census records, and wills. A graduate student research associate is helping each playwright by answering questions about, for example, whether a slave would likely have done a given action, Linke said.

The playwrights came to campus for an orientation day, held three times to accommodate all schedules, during which Sandweiss gave an overview of the project and Linke presented a range of documents. The playwrights toured campus and the town to physically inhabit the space that the research concerns, LaPenta said.

Sandweiss also provided them with a list of 30 possible topics, dealing with matters such as particular places in Princeton, legality and historical institutions, and certain documents like the 1830s journal of a University student who went on to serve as a missionary in Liberia.

The playwrights will submit drafts in March. Since McCarter reached out to them in August, it limited each piece to ten minutes to ensure they could meet the deadline, LaPenta said.

Following standard practice for short staged readings, rehearsals will begin only up to two days before the performance. The short window increases affordability as well as the odds of securing better actors, who can fit the work into their busy schedules. McCarter will probably choose professional actors, including from New York and Philadelphia, because the production date is fast approaching, LaPenta explained.

“Our goal for the two days will really be to focus on the text and how to best communicate that clearly, and hopefully also add in some elements that will make it feel like a performance and have an emotional impact on the audience,” LaPenta said.

Following an academic symposium about the project, the performances, directed by Patricia McGregor, will take place on both Saturday, Nov. 18 and Sunday, Nov. 19. After the last staging, McCarter will hopefully convene a panel of the playwrights, community members, and scholars to discuss the themes of the pieces. Beyond that weekend, the plays might continue living on in some form, according to LaPenta.

LaPenta estimated that McCarter will spend roughly $50,000 across two fiscal years for the endeavor. It received grants from the New Jersey Council for the Humanities, Mathematica Policy Research, and the Princeton University Histories Fund administered by the Office of the Provost.

She added that the material encountered through this partnership is already influencing the way that McCarter staff as Princeton residents and employees view their community, so she looks forward to sharing the project with more individuals.

“When we walk this campus, we are part of a long line of people who came before us, who did things, who made choices, who had assumptions,” Linke said. “We have to know our past and know it fully to be in this moment, to really understand what we've benefited from, why we're here at this point in time and not somewhere else.”