Once upon a time, Congress passed a law aimed at ensuring that university community members, particularly current and prospective students and their families, could access accurate information about campus crime. Such information would allow them to judge safety levels and determine if a particular college is indeed the place they wanted a young adult to attend for four years.

The year was 1990, and the law is the Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act, commonly known as the Clery Act. It was passed after the law’s namesake was raped and murdered by another student in her own dorm room at Lehigh University. This was one of 38 violent crimes recorded at Lehigh in the three years between 1987 and 1990. Her parents claimed that, had they known that crime rate, they would not have sent their daughter there.

However, 26 years have passed and the law doesn’t seem to be fulfilling its original purpose of providing a full and clear picture of crime to the campus community. Among its problems: phrasing that allows campuses leeway when reporting crimes that occur on private property that is technically off-campus, despite these locations being incredibly popular with students. At Princeton, this means that the interiors of the eating clubs do not have to be included in the Clery reporting.

A primary requirement of the Clery Act is to issue a mandatory annual report of crime statistics. The report is made public to the community annually, so that everyone can have an accurate conception of the crime situation on campus. However, an investigation by The Center for Public Integrity has “found that limitations and loopholes in the federal mandatory campus crime reporting law, known as the Clery Act, are causing systematic problems in accurately documenting the total numbers of campus-related sexual assaults.”

One particular area in which this problem manifests is the boundaries of what crime scene setting is considered reportable. In addition to campus property, which must be included, incidents occurring on certain nearby “public property” and “non-campus buildings or property” must also be reported according to the law.

Of course, this ruling begs the question about what to do with locations like Princeton’s eating clubs, which maintain a vaguely defined relationship with the University. They technically comprise independent private properties adjacent to campus, but of course they’re also openly and inseparably tied to Princeton, and serve as the hub of student night life. In 1990, the court in the Sally Frank case, where Frank sued to require the eating clubs to admit women, determined that the clubs were not “distinctly private” because of their “association with Princeton University.”

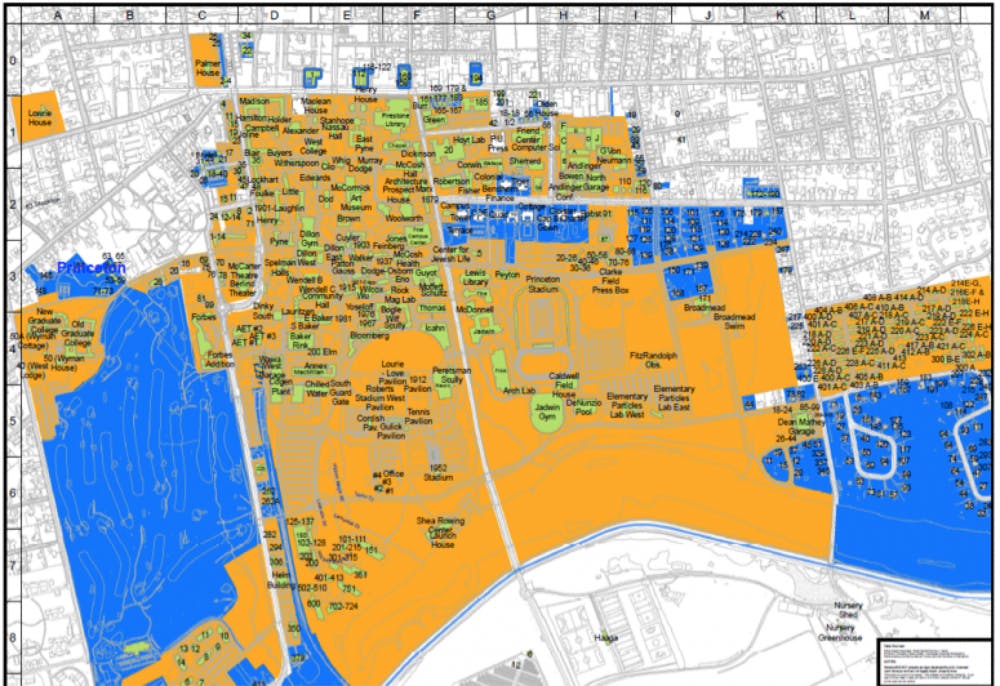

On the one hand, as reported in October, University spokesperson John Cramer explained, “all of the University’s eating clubs are on public property within or immediately adjacent to the campus, and hence fall under the University’s crime log coverage.” However, according to a map obtained by ‘the Prince’ in May, “the eating clubs themselves do not fall under the University’s Clery Act map.”

As the map shows, the lawns around the clubs are designated as area that is included as public property for the Clery Act. But, the club buildings themselves are white on the map, meaning they don’t seem to be included. This would suggest that if some sexual misconduct occurred inside a club, it doesn’t need to be included in the annual report. And given the connection between nightlife and sexual misconduct on college campuses, it doesn’t take much to realize that such a map likely would exclude quite a few crimes, even were they to be reported to Public Safety because of where they occurred, meaning the report might not provide as clear a picture of crime on campus as the law intends or as naïve readers might assume.

What Princeton is doing isn’t illegal. The Clery map meets all of the requirements in the Act. The problem is in the text of the law itself, which permits these loopholes and prevents the law from fulfilling its original, and important, purpose. Princeton and many other campuses just violate the spirit of the law by exploiting its poorly crafted language.

While the eating clubs illustrate a problem in the law’s language, this of course isn’t a loophole that just Princeton can abuse. I’m sure many colleges have nightlife hubs technically off campus and privately owned but, of course, closely associated with the college and pretty much considered campus by the student body, just like the eating clubs. In fact, in 2013 the LA Times revealed that the areas that were defined as off-campus at Occidental College largely explained how Occidental could get away with underreporting statistics while remaining in technical compliance with the Clery Act. Because the Clery Act leaves schools with wiggle room to define what areas off campus are and are not included, without making the distinction clear in the public report, these cases do not necessarily need to be reported to federal officials or the public.

The Act does not accomplish what it set out to do, much to the detriment of the campus community, and particularly students. Ultimately, the federal government needs to update the details within the law, and in the meantime, perhaps Princeton and other schools could choose to hold themselves to a higher standard and report additional data, similar to how they provide statistics from SHARE, but with a categorical breakdown; this will provide a more holistic and comprehensive picture of “campus safety” beyond the simple geographic finagling that occurs under the Clery Act. And until then, the community should analyze the Clery data from Princeton and all schools with a critical eye.