When thinking of “historical Princeton,” it is often images of Nassau Hall and Blair Arch that come to mind — it is, certainly, not the brick-tiled, rectangular building lodged between the Engineering Quadrangle and the Friend Center that represents campus for most people. Yet within this unassuming exterior stands the Mudd Library, responsible for housing just about all of the University’s illustrious history.

The Mudd Library was established in 1976 as the first building designed under Princeton’s energy conservation program. As part of Firestone Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections department, Mudd contains two lines of collections: the University archives and public policy papers from the 20th century. According to Sara Logue, assistant University archivist for public services, the library now has over 400 archives collections, including Princeton memorabilia, Board of Trustees minutes, Office of the President papers, historical photographs, all senior theses and all graduate dissertations.

“A lot of times people like to do research on famous alum — [the thesis of] Ted Cruz [’92] is very popular right now,” Logue said.

In addition, Mudd also houses student files for all alumni. While these files are unavailable for 75 years after the student’s graduation, due to the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, they are open for request and viewing afterward. This makes the library a popular source for researchers both within and without the University looking into an individual’s history, as well as those researching their personal family history.

“A lot of genealogical research is done using the student files,” Logue said. “It’s really like a treasure trove for people. If you think about it, your application is in there, and they’re great for just getting a sense of what [people] were like as a teenager, coming into college.” She added that the library has about 2,000 patrons a year and over 3,000 email requests for files and photograph duplications.

In recent years, one of Mudd Library’s most frequently received requests has been calls by recent graduates to see their own student files, including their applications and the Office of Admission’s comments. According to Yankia Ned ’17, a student employee at the library who worked as an assistant archivist there this past summer, there were approximately 20 requests per week over the vacation.

Another sect of Mudd’s frequent visitors are seniors, who often make the trek there to view the theses of their predecessors for reference. “A lot of seniors come in in order to get an idea of what their advisers have advised on before and to see what the expectations are of a thesis,” Logue explained.

“We’re doing more work to expand our libguides offerings — they’re basically guides that librarians make online that can lead you to more niche topics for research, so we made one for the senior theses,” Logue added. All libguides are available at libguides.princeton.edu. In addition, Mudd recently also hosted its first senior thesis open house to teach seniors how to access the theses in the collections.

Being renowned for its collection of senior theses also has its pitfalls, according to Special Collections assistant April Armstrong ’14. “People who do come here and know what we are, they know us as the senior thesis library, and while we do have all the theses, there’s a lot more here.”

And there is, indeed, much, much more. Ned, when she first began working at the library, was shocked by its sheer size. “It’s a very unassuming building, but it’s actually four floors,” she said. “There are three floors full of closed stacks, and it’s expansive. It’s anything you could ever want to learn about Princeton.”

For instance, over the summer, Ned was asked to scan some correspondence between President Woodrow Wilson, Class of 1879, and his wife, which she discovered to be love letters, complete with pet names. Meanwhile, one of her fellow student employees worked on digitizing the John Foster Dulles papers.

“Closed stacks” means that the library’s materials are available to be viewed in-house, in Mudd’s reading room. Since this is the case, many researchers physically come to Princeton just to use the library’s resources. Logue recalled projects such as a researcher writing on dining in universities who looked into primary sources of the eating clubs’ histories, as well as a novelist who spent time in the archives to research Princeton as the backdrop for her book. For students, requests to see materials can be made online after registering once on the Princeton University Libraries website.

“It seems limiting, but it’s for the protection of materials,” Logue said. “We have things from 1746 and earlier, and we want the things from today to still be available hundreds of years into the future, so that’s why we take such care.”

In the meantime, the library has been working toward digitizing its materials to be made available online. Currently, all Board of Trustees minutes are available online; they serve as useful overviews of the University’s activities and concerns at any given point in its history.

“While we are making great strides in trying to get things digitized, there are a lot of materials here — we have over 40,000 linear feet of materials,” Logue explained.

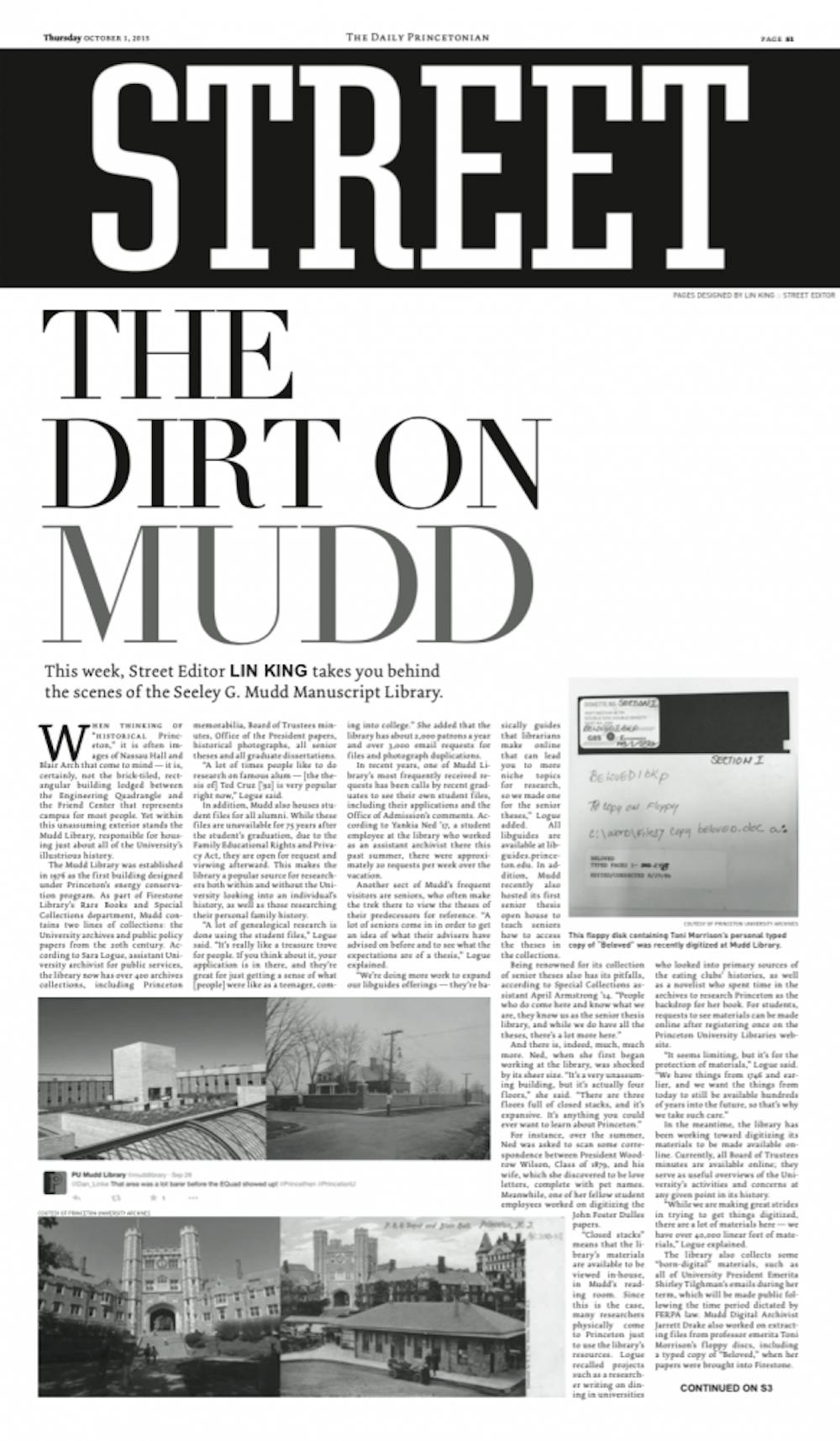

The library also collects some “born-digital” materials, such as all of former Dean of the College Valerie Smith’s emails during her term, which will be made public following the time period dictated by FERPA law. Mudd Digital Archivist Jarrett Drake, Elena Colon-Marrero and Allison Hughesalso worked on extracting files from professor emerita Toni Morrison’s floppy discs, including a typed copy of “Beloved,” when her papers were brought into Firestone.

To better share its many resources with the Princeton community, particularly the students, Mudd has made efforts to expand its online presence via social media. The library not only has two WordPress blogs but also Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr accounts.

Armstrong, who is responsible for pioneering and managing much of the social media content, explained that each platform has a slightly different audience. The library blog is more traditional, with more in-depth written pieces, while the Reel Mudd blog has audiovisual materials, including a video of American Hall of Fame basketball player and former New Jersey senator Bill Bradley ’65 playing basketball while at Princeton.

Meanwhile, Twitter is generally used for sharing with other libraries and special collections archives across the world, Facebook for connecting with alumni and Tumblr for current and prospective students. Armstrong runs various regular series on the different platforms: “This Week in Princeton,” with four things that occurred that week in the past; “Menu Mondays,” records of old menus from the University; “Tiger Tuesdays,” with pictures of tigers on campus throughout time; blog posts by staff and students on Wednesdays; and “Throwback Thursdays,” with a photograph or piece of memorabilia from the collections.

Most recently, Mudd hosted the “#Princethen” campaign on Twitter in September, asking students and locals to tweet pictures of the current campus, which Armstrong would then match with an old image of the same site for comparison. The campaign was inspired by a similar one done at the University of Missouri last year.

“I was hoping that by doing the campaign, we would get people to know more about the campus, but also get to know us,” Armstrong explained. “I just think that the history of a place is important to know. What was it like before? Who was here? Why did this get this way?”

“One of the frustrating things about working at a place with so much material is, we have people who come through the doors and say, ‘What is this place?’ Part of it is because we are nestled here in the sciences … although we were here first!” Armstrong said.

In spite of its low-key status and the relatively long trek from central campus, Mudd Library does offer answers for just about any question one can ask about Princeton’s past.

“I think it’s an underused resource for sure,” Ned said. “We go to such an old institution and … it’s good to actually go into the history and see everything behind it. So much research and knowledge can be gained from it — and not just the quote-unquote serious stuff; it can be fun things, like old P-rades and Pre-rades, a bunch of scrap books.”

“Anything you want to know about Princeton is there. Everything is so old, it’s amazing,” she added.

Correction: Due to inaccurate information provided to The Daily Princetonian, an earlier version of this article misstated whose emails Mudd Library currently holds. The Library has former Dean of the College Valerie Smith's emails. Additionally, Elena Colon-Marrero and Allison Hughes joined Jarrett Drake in extracting files from Toni Morrison's floppy disks. The 'Prince' regrets the errors.