After Pope Francis’s speech to Congress last week, liberals and conservatives alike rushed to claim the mantle of the pontiff’s endorsement for their favorite causes. A columnist for The Hill wrote that “if Pope Francis could endorse a candidate, he’d choose Bernie Sanders.” Both Sanders’scampaign and his Senate office have explicitly touted the similarities between his campaign rhetoric and the Pope’s messages on economic inequality and climate change. And for their part, conservatives praised the pontiff’s (implicit and glossed-over) admonitions on same-sex marriage and abortion. In fact, just hours after the Pope left the Capitol, Republicans in the Senate held a vote to defund Planned Parenthoodwhich fell short of the 60 votes needed to advance.

While the Pope certainly sounds like Bernie Sanders when it comes to immigration, inequality and climate change, to call him a liberal Democrat would surely be a mistake, as several columnists have noted over the past few days. And while as a liberal Democrat I’m thrilled the Pope has succeeded in loosening the “Religious Right’s” self-declared monopolistic claim over religion in American politics, the fact that neither party can claim the pontiff’s views as completely its own should in and of itself be cause for praise.

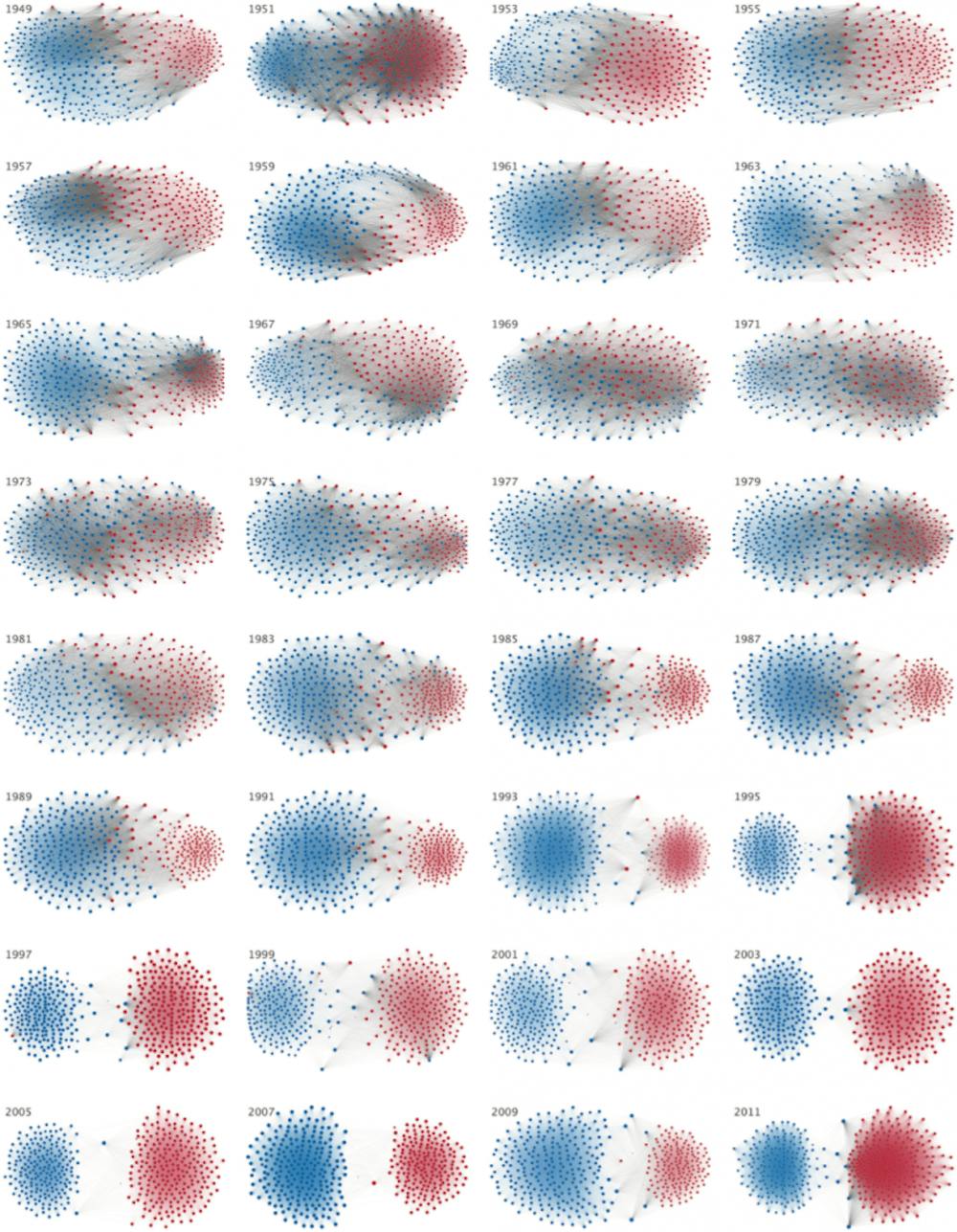

If there’s any single thing that’s destroying Congress’s ability to function, it’s ideological rigidity. As researchers have recently shown by analyzing congressional voting data from the last 60 years, Congress has gradually transformed from a place where members frequently crossed the aisle to vote for bills sponsored by the other party to a nearly-perfect us-versus-them fight between two voting blocks. This, of course, has led to the stunningly dysfunctional bipartisan system we have now; in previous decades, having a Congress of one party and a President of the other didn’t mean nearly as much as it does today.

Those of us who were born around or after the time of Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America” (which cemented the trend towards partisan voting in 1994) have been conditioned to see this system as normal, but historically, it is anything but. Today, it is rare to see more than five members vote against their party on a given motion or bill — in fact, in 2013, House Republicans and Senate Democrats broke records for voting along party lines (at 92% and 94%, respectively).

If anything, the legacy of the Pope’s speech to Congress should be that the pontiff can’t be easily placed into one column or the other. His liberal views on economics, the environment and immigration would clearly make him a Democrat, but his views on same-sex marriage and abortion obviously side with the Republican base. In a political system that’s gotten so used to putting people into neatly defined boxes, Pope Francis provided a refreshing reminder that it doesn’t have to be that way.

In fact, probably the least common political ideology among major American politicians today is “socially conservative, fiscally liberal.” While the opposite certainly exists (e.g. Governor Charlie Baker (R — Mass.) and Senator Susan Collins (R — Maine)), there simply aren’t any major politicians today who fit the label Pope Francis most closely aligns with. So regardless of the fight to claim the Pope’s endorsement on one issue or the other, it should be regarded as inherently valuable and even historic that a major figure holds such unorthodox views.

Especially coming after Speaker of the House John Boehner’s resignation, which has largely been attributed to the “ungovernable” nature of the Republican caucus (thanks to an intransigent and uncompromising far-right wing), it is refreshing to be reminded that ideological intra-party diversity isn’t something to be hated or shamed. Uncompromising rigidity, which the Pope himself chided during his address to Congress, however, should be. If there’s one thing we should hope for in the wake of the Pope’s speech, it’s that more legislators will cross party lines on the myriad no-brainer, should-be-bipartisan bills that reach the House and Senate floors but receive no news coverage. The Planned Parenthood vote, which obviously doesn’t qualify as such a bill, shows however that those hopes are largely unjustified and that unyielding partisanship is sadly here to stay.

Ryan Dukeman is a Wilson School Major from Westwood, Mass. He can be reached at rdukeman@princeton.edu.