Street sat down with Shirley Tilghman, who from 2001 to 2013 served as the 19th President of Princeton University. The first female to hold the position, Tilghman discussed her accomplishments as president, gender dynamics at Princeton and the national gender equality movement.

Daily Princetonian:What would you say was your greatest accomplishment as President of Princeton University?

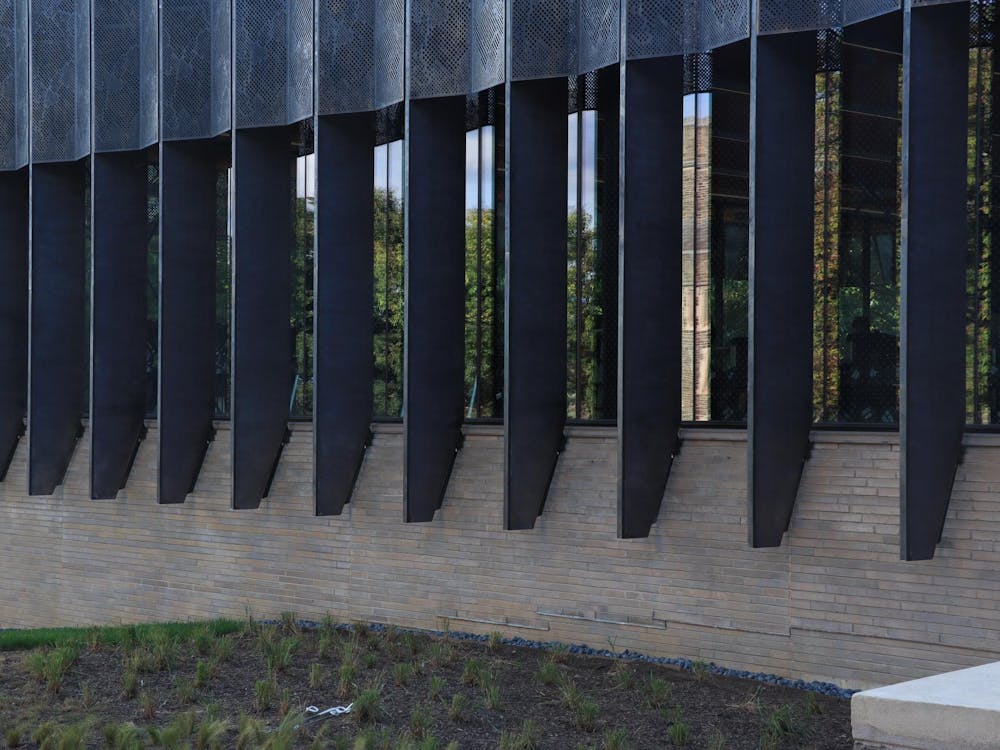

Shirley Tilghman: That is a difficult question, as I don’t think there was one single thing that stood out above others. I could point to the increase in the number of students who receive financial aid, thereby making Princeton more accessible for students from all income levels; the [Lewis] Center for the Arts that increased so many opportunities for students to pursue the arts; the [Princeton] Neuroscience Institute; [the Center for] African American Studies.

DP: Was there a moment during your tenure when you felt undermined because you were a woman?

ST: No — I never felt undermined. I think it took some time for some alumni to get used to a woman president, but I never felt as though that temporary unease undermined my ability to serve.

DP: In your experiences, how has Princeton changed in its views on women’s rights and gender equality?

ST: Two major initiatives during my time have improved conditions for women on campus: the Task Force on the Status of Women Faculty in the Natural Sciences and Engineering was instrumental in improving the recruitment, retention and experience of women scientists and engineers, and the Steering Committee on Undergraduate Women’s Leadership has brought a greater focus on the ways in which we are preparing young women for the world after Princeton. I also think it has helped to have so many women serving in senior roles in the University and going on to lead other institutions.

DP: How has Princeton changed in its representation of females in the student body and faculty?

ST: The percentage of women in the undergraduate student body has increased only modestly because women were already well-represented. The percentage now is routinely just below 50% because of greater interest in engineering on the part of male applicants. I don’t know the current number of women on the faculty, but that has been increasing as well, but very slowly.

DP: Specifically, how would you describe the current state of female representation in scientific fields? What improvements would you recommend, if any?

ST: The picture is mixed. In fields like molecular biology and psychology, women are very well-represented in graduate school, but their numbers fall off at the faculty level. At the other extreme are fields such as physics and mathematics where women are under-represented at all stages. Some of the problem is related to [the] way we teach science, beginning in primary school, and some of it is related to deeply ingrained cultural practices within the disciplines that are not welcoming to women in general. There is good evidence to suggest that women need more effective mentoring in order to persist within such cultures.

DP: Nationally speaking, would you say that the goals of the gender equality movement are being met? Why or why not?

ST: I have been worried for some time that the improvements in the status of women in our society have slowed in recent decades, after remarkable gains in the wake of the feminist movement. It is very clear that until we find better solutions for working parents — including paid maternity leave and proper child care options — the progress is going to be slow.

DP: What advice would you give to the other women of Princeton?

ST: [Find] what truly interests you and [what you] are reasonably good at; then pursue that career with determination and focus. Choose your mentors well, and don’t let anyone discourage you because you are a woman or turn you into a victim.