Until recently, I thought that limes were just unripe lemons. I had always been perplexed about why limes are sweeter than lemons, but then again, I am rather easily perplexed by a great many things.

Until recently, I thought that limes were just unripe lemons. I had always been perplexed about why limes are sweeter than lemons, but then again, I am rather easily perplexed by a great many things.

There are a lot of clever sayings about what to do when life gives you lemons but not a whole lot of folksy wisdom about where those lemons came from in the first place. Certain epistemologists could make the argument that without actually sitting yourself down in front of a lime when you've got a lot of time to kill, you can't really be certain that it won't eventually turn into a lemon.

After all, plenty of things start out green and then wind up yellow —bananas, for instance. Green bananas, the kind that the dining hall never seems to run out of, are nasty-tasting and tough to eat, but they become yellow and soft and delicious after you sneak a few out in your coat pocket and leave them lying around in your room for a while. Leaves, too, start green and finish yellow. The leaves of the gingko tree between the University Chapel and East Pyne are green in the spring but explode in a brilliant overnight shower of gold in the fall. If those leaves belonged not to a gingko but to a lime or lemon tree, my friends might never have discovered my gap in knowledge, and I might have been saved a good bit of ridicule.

But they did discover it, and for a while it was as though I had revealed that I still believed in Santa Claus or kept a jar of loose teeth set aside to cash in on a rainy day. “How could you have not known that? Didn't anyone ever tell you? Is that even something that has to be told to you?”

How could this crucial piece of knowledge have managed to slip past me? When are you supposed to learn that, although juvenile lemons are indeed green and bumpy and look quite a bit like limes, the two are not actually the same thing? After the study of algebra? Before?

I thought back to my boyhood in search of an explanation. I realized that my mother had never really used lemons or limes in her cooking, eschewing them for ingredients like soy sauce and sorghum vinegar. So I texted my brother —“Did you know limes and lemons are different fruit?” —thinking that someone who shared a common dietary history with me would surely share a common level of dietary ignorance.

“Uh / Yes / How did you not,” came his response. Maybe he'd learned it in poetry class.

Desperate to identify a kindred soul, I began to slip this topic into conversation with friends. I succeeded only in further confirming my suspicions that I am the only person in the world who missed the memo explaining that limes are not to lemons as piglets are to pigs.

It is very much in the spirit of Princeton to be competitive —about grades, about social standing, about career prospects. A few of my friends recently made me aware of a course offered here in which a significant portion of students' grades is determined by their ability to sell more virtual orange juice than their classmates can. My private embarrassment concerning citrus fruits aside, I find it oddly comforting to know that, although we find ourselves in an environment in which we often have the opportunity to compare ourselves harshly to our peers, most everyone seems to understand that limes are not just unfulfilled lemons.

“Everybody is a genius,” Einstein once said, apparently with a straight face. “But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” Likewise, if you judge a lime by its ability to squeeze out a glass of lemonade —or a glass of orange juice, for that matter —you will find yourself sorely disappointed in that lime. But limes can take you many places that lemons cannot: Only by starting out with a lime can you wind up with limeade, or key lime pie, or that beach-ready Bud Light variant that Anheuser-Busch hawks in the summertime. Every fruit has something unique to bring to the dining room table. Every person, too.

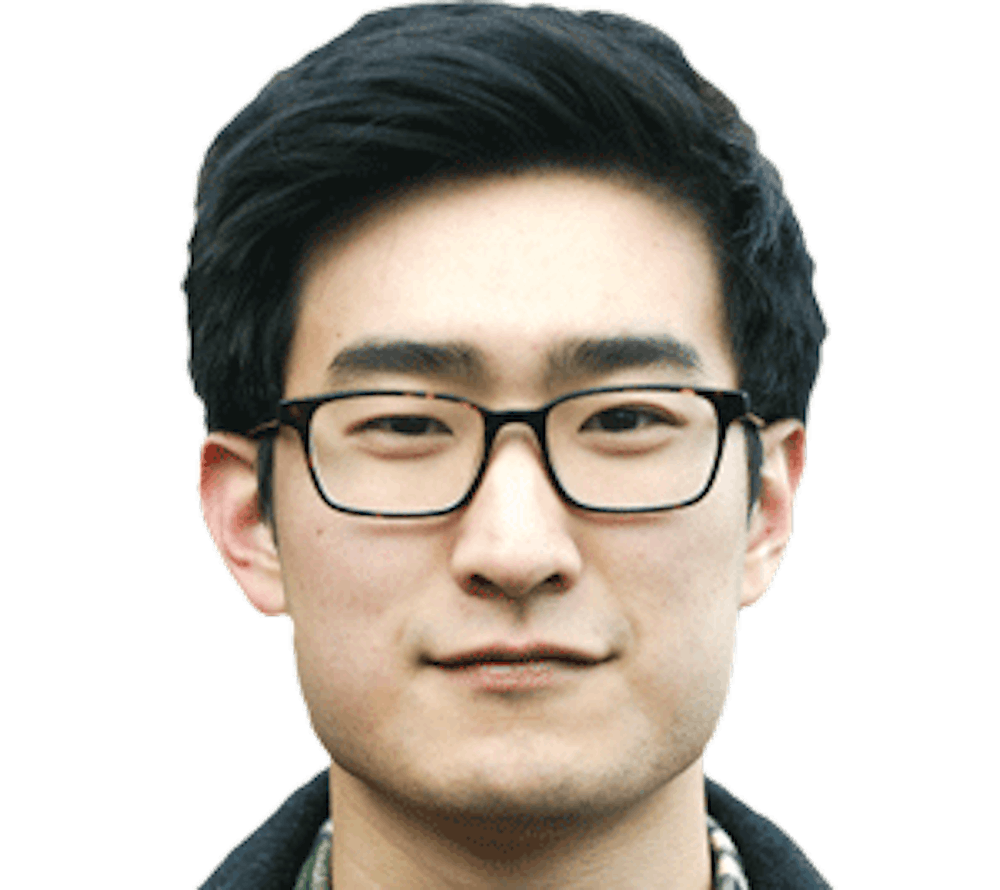

Daniel Xu is a molecular biology major from Knoxville, Tenn. He can be reached at dcxu@princeton.edu.