Editor’s note: The original article mistakenly referred to Q'nnections, a queer mentorship program, as an existing LGBTQ+ community space. In fact, Q'nnections is no longer an active group.

“Princeton might be gay, but it isn’t very queer,” said alumnus and social media star Griffin Maxwell Brooks ’23 in a 2022 Features article for The Daily Princetonian. This difference lies in the fact that being queer is an identity, but queerness encapsulates a culture. Like many colleges, Princeton has a far higher percentage of queer individuals than America as a whole — based on surveys done by the ‘Prince,’ 69.2 percent of the Class of 2024 identified as straight, and 75.3 percent of the Class of 2027 identified as straight. Nationally, that number is around 86.3 percent. And as far as trans students go, they comprised about 2.6 percent of the Class of 2024, while only 0.5 percent of adults identify as trans nationally. So why is queer visibility – the presence of queer spaces and queer culture – nonexistent on campus?

While a significant population of Princeton undergraduates fall under the LGBTQIA+ umbrella, many do not step into the rain, failing to gather these identities into a tangible community. And I get it — with all the preexisting pressures at Princeton, consciously cultivating a culture of queerness is the last thing on many students’ minds. But queer people and queer Princetonians have been putting this essential project off for decades, and it’s time for that to change.

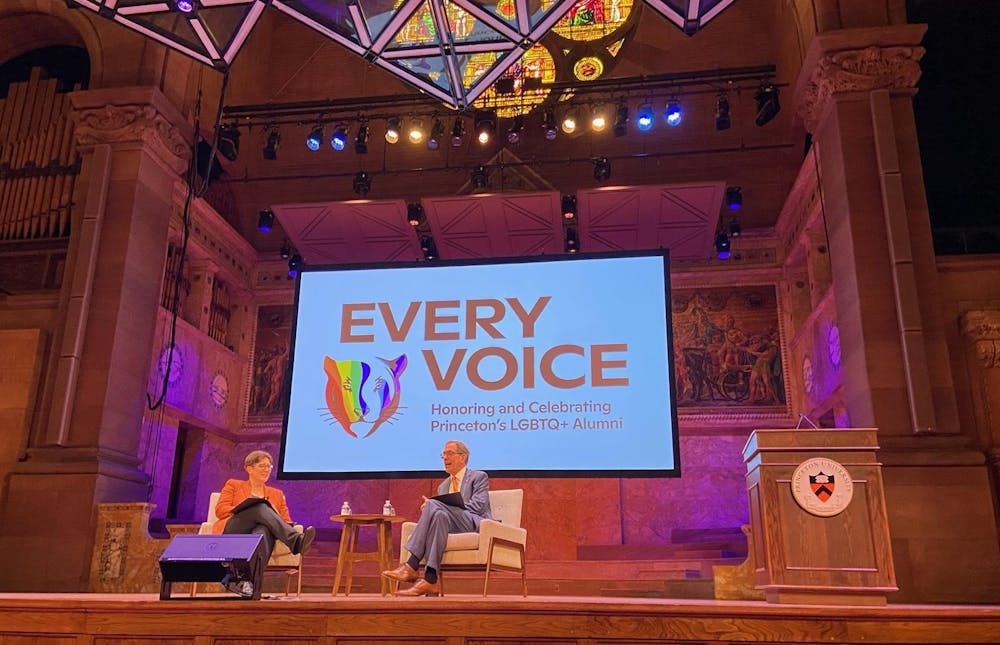

This past week, I attended the Queer & Asian Student + Alumni Mixer auxiliary to the Every Voice: Honoring and Celebrating Princeton’s LGBTQ+ Alumni conference. There, the alumni — among them Helen Zia ’73, a noted queer and Asian-American activist and a member of Princeton’s first graduating class of women — reflected on how reluctant they were to return to Princeton after graduation because of the ostracization they faced during their undergraduate studies and at Reunions. Collectively, the alumni speakers wished that they were able to see and belong to a community of queer Princetonians during their time. This small gathering of 20-odd queer people, this small display of solidarity, elated these queer alumni because of the sheer fact that we had come together in community.

If this small collection of queer people could be so heartening, then a truly visibly queer community could bring so much joy to students, faculty, and alumni. There are so many queer Princetonians and queer social circles, yet there is simply no large coalition of queerness that a queer person can point to and recognize as their community. In a 2023 column in the ‘Prince,’ Managing Editor Lucia Wetherill reflected on this: “That these beautiful and essential sapphic friendships do, in fact, exist, makes the absence of a community all the more noteworthy and painful.”

Without queer visibility and a strong queer community, many queer students report feeling alienated. As Maxwell Brooks put it in that same Features article, “as a queer, and gender nonconforming person, I often feel unvalued, unwelcome, and sometimes unsafe here at Princeton University.” And, in an article by AJ Lonski ’23, he wrote that even within tight-knit communities like the Wrestling team, homophobia runs rampant: “[an upperclassmen wrestler] stated, ‘The day that there is a gay person on this team is the day that the wrestling program has gone to s***.’ Hearing that intolerant sentiment was heartbreaking, but not surprising.” An increase in queer visibility will create more tolerant and open communities across campus, not just in queer spheres.

Queer visibility as a concept is not just an individual being visibly queer or having distinct self-expression, nor is it simply the existence of queer communities — it’s the presence of robust, extant, and inviting spaces on campus whose presences are impossible to ignore, composed of the combination of queer communities and visibly queer individuals. While the Gender + Sexuality Resource Center's (GSRC) resources are significant and much-appreciated spaces of LGBTQIA+ comfort and community, their presence is not pervasive. Therefore, ever-present communities of queer culture must come from unadulterated queer self-expression and culture which builds upon the efforts of the pre-existing queer spaces and affinity groups. While affinity groups do hold events in University-created spaces, these events are often under-attended. For true queer visibility to exist on campus, queer joy must fill eating club basements and queer community must crowd out lecture halls.

If we are to develop a truly robust queer culture, that requires all of us — the queer community and its allies — to step up and do our part. We need to commit to attending affinity group and guest speaker events like those included in the Every Voice programming. We need to ensure that queer people in all of our clubs feel safe and encouraged to express their identities. We even need to show up to queer-centric nights out. We need to show the full force of the queer-and-allied community on campus to dispel any notions that Princeton is not a space for queer people.

That queer culture is not an integral part of Princeton is a disservice to every Princetonian, queer or not. Building visible queer communities at Princeton allows for exposure to a dynamic and vivid culture which is not often easily accessible, even though it should be. Precisely because there is an absence of Queerness and queer communities in an institution with many LGBTQIA+ students, we as individuals must be more intentional in creating queer visibility. We, as the queer students of Princeton, must work toward a Princeton which genuinely feels welcoming for queer & questioning people, to create a culture of queer joy and queer love, to show our queer Princetonian forebearers that what they overcame was not for nothing, and that Princeton is a place for everyone.

From queer social circles and individual queer people, a queer collective must emerge. We must provide an empathetic space for queer & questioning Princetonians alike, to those queer people who may not feel comfortable expressing their queerness and those who may not be able to find support on their own. We must create a space where everyone can come into contact with queer joy and queer pride and, perhaps, revel in their own.

Callisto Lim (they/she) is a first-year from Houston, Texas, planning to major in Civil and Environmental Engineering on the architecture track. They have previously been published in the New York Times, Angles Literary Magazine, and more. To reach her, email callisto[at]princeton.edu.