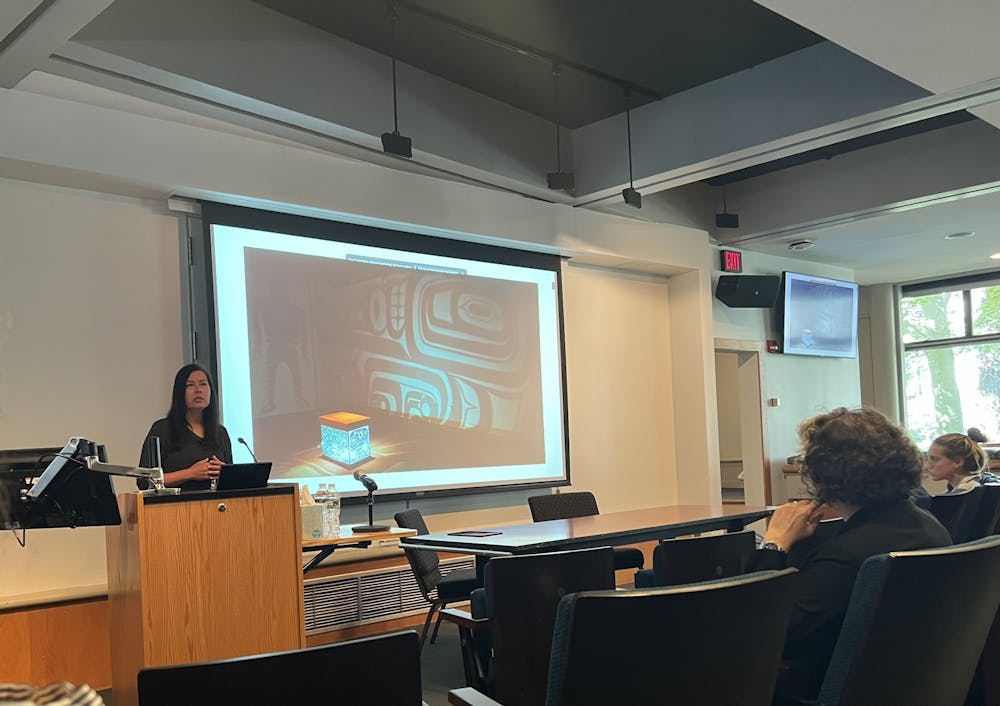

Artist Marianne Nicolson of Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nations spoke on Princeton’s campus on Friday, Oct. 7 about her community, life, and artwork in a conversation with art and archaeology professor Rachel DeLue.

Friday’s conversation, held in Betts Auditorium, was co-sponsored by the Princeton Art Museum, Institutional Equity and Diversity, and the Office of Religious Life.

Nicolson opened the event with a discussion of naming practices, explaining that Marianne Nicolson is her English name. Nicolson said that Indigenous cultures treat naming as a cumulative process, and community members acquire new names as they enter different stages in their lives. When discussing the significance of names, Nicolson stressed what would be a recurring theme throughout the talk: she prioritizes working with and for her community, rather than only forming her name as an individual artist.

“It’s an honor to have given your life to your family and community,” she said, referencing names given to people at the end of their lives.

Nicolson also presented several photographs, mostly highlighting her community’s land and her artwork. Her artistic practices are intrinsically linked to her interest in natural landscapes, and her art declares her people’s “presence on the land.” The Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nations consist of four tribes and are from Kingcome Inlet, Canada.

Nicolson’s art often acts as a statement of visibility, criticizing the capitalist corporations that are destroying her land. For example, her massive pictograph, “Cliff Painting,” has been installed to loom on the side of a rock structure hugging the river she lived next to as a child. The piece serves to remind logging companies that spray pesticides on the land about the damage they are causing. According to Nicolson, the piece has become “a part of the psychology of the community,” connecting her own work, her community, and her land to one another.

Nicolson progressed through more images of her multimedia artworks and described how she has encountered institutional spaces as an Indigenous artist. She once created a banner and light show to hang on the front of the Vancouver Art Gallery, a space that once symbolized the British Columbian Court. The banner was designed to question the use of institutional spaces in the context of colonialism and transform the gallery’s architecture to speak to Indigenous experiences.

In addition to discussing her focus on environmental and social injustice, Nicolson described her techniques as an artist. Nicolson prefers multimedia art and enjoys incorporating light into her work. She explained that a breadth of media allows her to explore her culture as an artist without appropriating original forms. Her interest in light also connects to her culture and spirituality.

Her piece “Feast of Light and Shadows” embodies her interest in the intangible and spiritual. This work is located in a mostly sparse room teeming with windows. As the light travels across the room, it fills a series of bowls placed on the floor, eventually creeping up the wall to illuminate an image of a building from her home. Some of her relatives can be seen in the photo of the building, underscoring her emphasis on community and family.

“It was all about these wonderful ways of being the world and the spirit,” she said.

Nicolson’s art questions the material emphasis of a capitalist society. She explained that Indigenous artists have been pushed to commodify sacred and culturally significant art to satisfy consumer markets. Nicolson has also struggled with notions of physicality and consumerism in her own work.

Another of her pieces, “Sea Captain,” is a large, suspended sculpture that faces downward. She explained that the sculpture reaches outward in a gesture of taking, representing the colonial impulse to take from Indigenous populations. While the sculpture is strikingly beautiful and detailed, it also carries critical symbolism of the piece. Nicolson described the struggle of balancing beauty with the message she was attempting to convey. “Part of me was enamored with the spectacularity that came to our shores,” she said. However, she reminded listeners of the devastating impacts that such “spectacularity” has had on Indigenous people and their land.

The conversation between Nicolson and DeLue, as well as Nicolson’s responses to audience questions, remained centered on the artist’s deep interest in community, natural land, and spirituality — abstract connections that transcend consumerism and capital.

“There is a different way to live. There is a different way to be,” she said, underscoring for audience members the importance of shaping their own lives.

Isabella Dail is a member of the Class of 2026 and a contributing writer for The Prospect at the 'Prince.' She can be reached at id7289@princeton.edu.