Judge Amy Coney Barrett, a judge in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit and Professor at the Notre Dame Law School, opened her Oct. 17 talk on campus by arguing, “The story of the United States can’t be told without the Constitution.”

Barrett, who delivered the annual Walter F. Murphy Lecture in American Constitutionalism, went on to allege the U.S. Constitution’s superiority derives from its concision and continuity, as opposed to the constitutions of the United Kingdom and France.

“The average constitution is replaced every 19 years. Ours [has been] the same for 250 years,” she said.

Barrett explained that the significance of the Constitution lies in the very geography of the United States. She recalled that the creation of West Virginia revolved around a disputed interpretation of Article IV of the Constitution, which stipulates that a new state cannot be established without the consent of the surrounding states.

Virginia did not express explicit consent for the formation of West Virginia, which split from its parent state during the Civil War. Barrett said that Abraham Lincoln grappled with this constitutional dilemma, but justified the lack of consent since secession would be considered unconstitutional to begin with.

Barrett further related the Constitution to congressional power, citing the example of Alexander Hamilton’s establishment of the First Bank of the United States. Hamilton served as the first Secretary of the Treasury.

According to Barrett, Congress was concerned that such a national institution would infringe on the powers of individual states. Hamilton, however, justified the institution by using the Constitution, since having such a bank would allow the country to hold up the ideals of citizens’ success and happiness, values that the Constitution enshrines.

Barrett observed that this rationalization has since been validated, given that the Bank of the United States eventually allowed for the creation of a minimum wage and the establishment of Social Security.

This relationship between the Constitution and Congress is, according to Barrett, mirrored in the relationship of the document to individual people, as illuminated by the issue of slavery. Barrett argued that the debate over abolition had both constitutional and moral sides, since the Constitution had to be amended for slavery to become unconstitutional.

She then extended this view of a debate between morality and constitutionality to contemporary issues, alluding to her view that abortion and same-sex marriage present similar contested understandings of what is constitutionally and morally correct. She did not specify where the conflict lay within these two particular cases.

Barrett has previously faced criticism from politically liberal organizations over her views on abortion and gay marriage. In 2017, 27 LGBT advocacy groups and 17 women’s rights groups wrote to the Senate Judiciary Committee, calling on its members to oppose Barrett’s nomination for the Seventh Circuit. In 2003, she published an article calling Roe v. Wade “an erroneous decision.”

In 2017, Barrett, then an appeals court nominee, drew national attention during her Senate confirmation hearing, when some senators questioned whether her religious convictions would unduly inform Barrett’s judicial philosophy, particularly in light of her previous writings on the matter. During the hearing, Senator Dianne Feinstein (D, Calif.) controversially claimed, “the dogma lives loudly within you.”

Despite those concerns, the Committee voted to confirm Barrett.

In the talk, Barrett then shifted her focus to the active role the Constitution serves today.

“We need more than political agreement to get things done,” she said, adding that the Constitution speaks to this effect, given that it supersedes politics with well-defined guiding principles, which must be followed.

She deemed the Constitution a “supermajority checker,” serving to keep even the President accountable.

Still, Barrett pondered whether “it would be better if Congress were free to pursue the best policy” without this constitutional restraint. She argued that doing so would most likely have allowed slavery to be abolished sooner.

Barrett praised the diverse population of the United States, saying that “we are all under one roof” and in that way unified. She argued, however, that the Constitution divides us through federalism. She claimed that the United States is, “after all, one country and not fifty states,” and that the Constitution distinguishes between state and national law.

Barrett also discussed her role as a judge and reflected on the act of deciding on cases and laws.

She compared these processes to a scene from Homer’s Odyssey, in which Odysseus confronts the Sirens. Barrett noted that “democracy is dangerous” insofar that it might be attractive for a democratic majority to, for instance, “trample civil rights in [a] time of a national crisis.” As agents of the Constitution, the courts, as however, bar that from happening.

She added that this fact provides consolation in what she described as a “polarizing time.” She finished her lecture by quoting Benjamin Franklin, saying that the constitution is dynamic and not static, because “in this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes.”

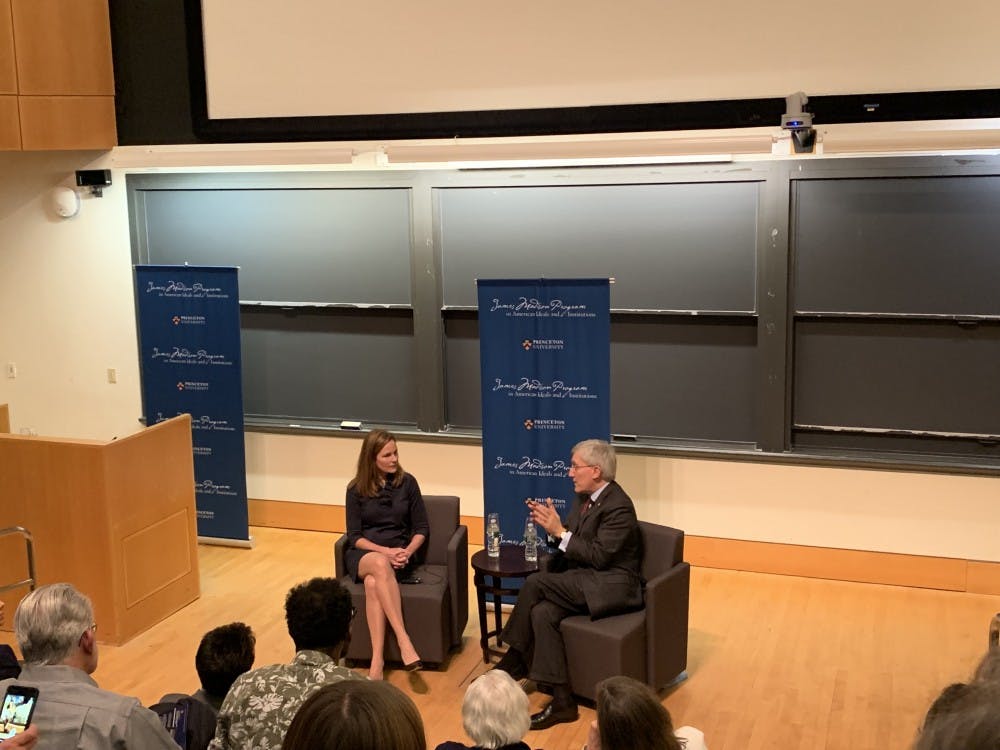

Robert P. George, McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence, moderated the event. George currently occupies the professorship that Walter Murphy, for whom the annual lecture is named, once held.

After Barrett’s remarks, George joined Barret in an open conversation. He spoke about what he views as “American exceptionalism.”

George postulated that unlike the constitutions of other countries, that of the United States is unique in that it “constitutes the American people” — namely, that the people are defined in and by the Constitution.

He said, “the French will continue to be the French if they throw out their constitution,” but claimed this assertion does not hold true for Americans, for whom the Constitution begins with the assertive phrase, “We the People.”

Barrett agreed, arguing that Americans frequent museums to observe and learn more about the Constitution, and that this is not the case in other countries, tempering her assertion by adding that “she hasn’t seen surveys” proving this fact.

George added that Germany has a “good constitution that we [the United States], in effect, imposed,” a remark followed by laughter.

The floor was then opened for questions, among which included a student asking the Judge for her thoughts on how the likely appeal in the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard case will conclude. Barrett refused to answer on the grounds of judicial impartiality.

The lecture took place at 4:30 p.m. in the Friend Center, room 101, on Thursday, Oct. 17.