One afternoon this past December, Naomi Hess ’22 received a text from her friend, Emily Weiss ’22, asking if Hess wanted to play Cards Against Humanity in Weiss’ six-person suite later that night.

Although it only takes Hess two minutes to reach Weiss’ suite in Gauss Hall from her own dorm in 1976 Hall, Hess couldn’t go — the building does not have an elevator and is not accessible for wheelchair users like Hess, who has muscular dystrophy.

Hess is a staff writer for The Daily Princetonian.

The entrance to Gauss Hall, which is one of many wheelchair-inaccessible buildings on campus.

Photo Credit: Jon Ort / The Daily Princetonian

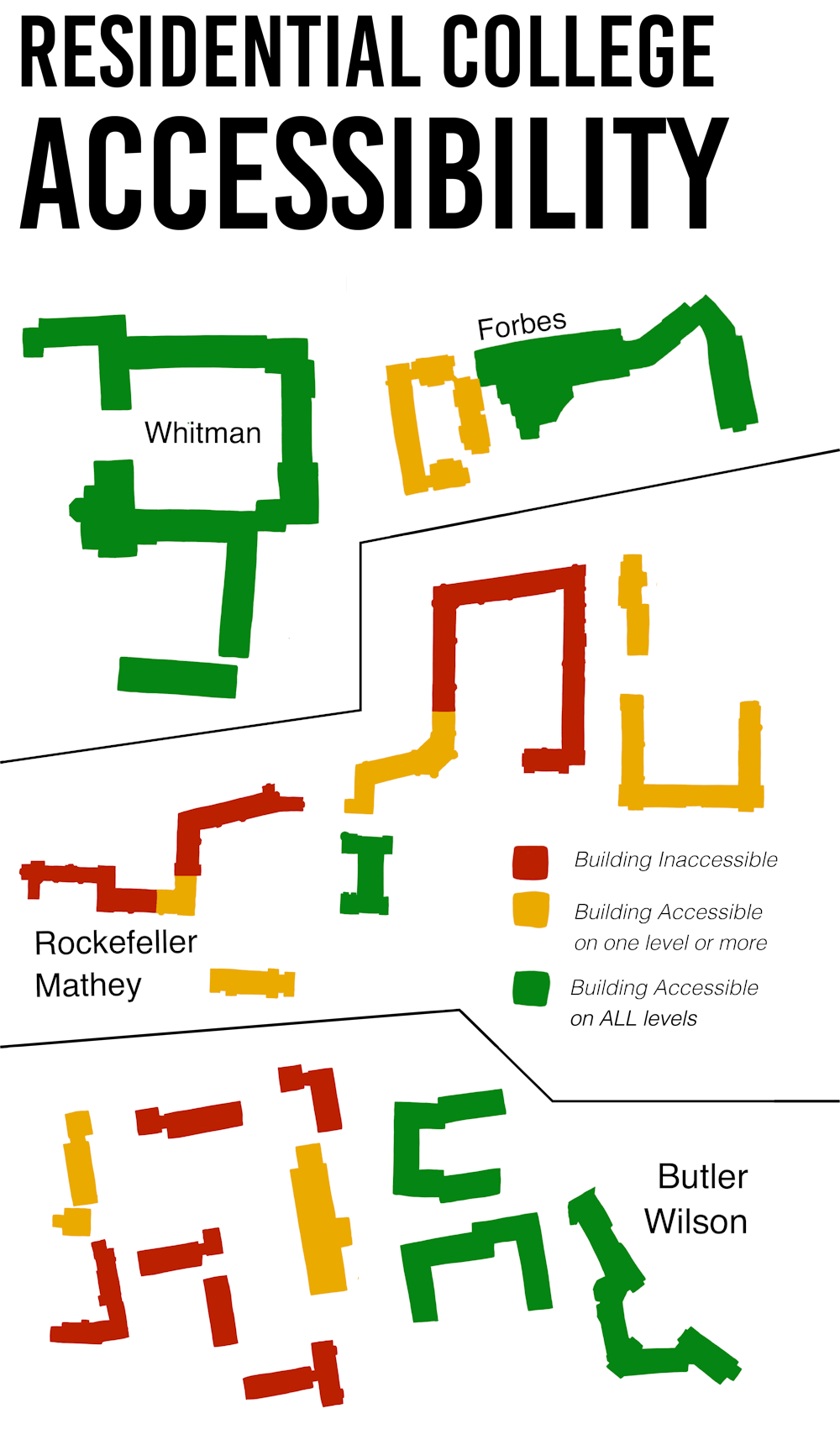

Approximately 60 percent of the University’s 200-plus campus buildings, excluding eating clubs, are not fully wheelchair-accessible, according to the 2017 accessibility campus map offered by the Office of Disability Services (ODS). The map marks wheelchair entrances and the accessibility of campus buildings.

Furthermore, eight out of eleven eating clubs lack full wheelchair accessibility, according to former Interclub Council (ICC) Chair Hannah Paynter ’19.

According to Hess, she is currently in talks with the ICC to post an accessibility guide online to inform students clearly and accurately about club accessibility.

The lack of accessibility to campus buildings and eating clubs makes it more difficult for students with physical disabilities to integrate into some academic and social communities on campus. Even when compared to other historic institutions like Harvard and Yale, Princeton trails behind in its accessibility efforts.

A 2011 report by the Institute on Disability by the University of New Hampshire concluded that if people with disabilities were a formally recognized minority group, they would be the largest minority group in the United States, composed of 19 percent of the population. Despite this prominence, students with physical disabilities at the University do not have a formal campus organization to foster a community among students with physical disabilities. Although the University’s ODS has made visible attempts to accommodate students with physical disabilities, more remains to be done.

ODS attempts to increase accessibility

According to Director of ODS Elizabeth Erickson, the office tackles the academic needs of physically disabled students by working with the Registrar’s Office to assign accessible classroom locations or to make adjustments to inaccessible locations.

For example, Hess’s freshman seminar, “Disability and the Making of the Modern Subject: From Wordsworth to X-Men,” was moved from McCormick to East Pyne, since the gravel pathway to McCormick was difficult for her to travel on with her wheelchair.

In some cases, inaccessible buildings have been refurnished. For instance, prior to the summer of 2017, Dickinson Hall, which houses the history department, was not wheelchair-accessible. However, after Valerie Piro, who uses a wheelchair due to a permanent spinal-cord injury, joined the department in 2017, the building was renovated to include a ramp and chair lift.

In addition to relocating classes, ODS also offers accommodating housing to students with physical disabilities: according to Assistant Dean of Undergraduate Students Bryant R. Blount ’08, when a student makes a request for a specific type of housing, he works with ODS, University Health Services (UHS), and McCosh Health Center to make a “very individualized” assessment based on the student’s medical need and the nature of the submitted request.

For example, Hess currently resides in a single with her own private bathroom in Butler College’s 1976 Hall.

“ODS is a helpful liaison in getting [me] things that I need,” added David Loughran ’20, who has muscular dystrophy and uses a wheelchair. “I know the people in the office ― if I needed something, it would be talked about.”

He and Hess also noted their appreciation for ODS’ snow-removal maps, which students with physical disabilities use to mark their routes to class that need to be cleared first.

Despite these efforts and successes, inadequacies still persist.

Gaps in ODS’ accessibility efforts

Many ODS solutions are reactive, rather than proactive: for instance, Dickinson Hall was renovated after Piro joined the graduate history department.

Even the creation of ODS was a delayed response to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), which “protects qualified persons with disabilities from discrimination in ... academics.”

According to Erickson, ODS was founded in 2006 — 16 years after the ADA was enacted. In the years before ODS was founded, students with physical disabilities turned to the Office of the Dean of the College for academic concerns and staff in the Office of the Dean of Undergraduate Students for housing and dietary concerns, explained Erickson.

According to an email from Deputy University spokesperson Mike Hotchkiss, under federal law, students have the choice of whether to self-identify as having a disability.

“The University has no other means to learn this information so it is probable that at any given time there are students with disabilities on campus who have not self-identified with ODS,“ Hotchkiss wrote in the email.

Both Hess and Loughran also revealed that they have rarely used the accessibility map because of how difficult the map is to read. Instead, both have found their way around campus by simply exploring the campus on their own. For instance, Hess spent half an hour to locate a wheelchair-accessible entrance to the Rockefeller/Mathey dining hall.

According to Hess, Whitman is the only residential college and dining hall to currently lack automatic door buttons. Hess has consulted with University Facilities about this problem, and Facilities is currently in the process of installing door buttons for the dining hall.

Furthermore, there is no formal campus organization that connects the community of students with physical disabilities. Hess, Loughran, and Piro all struggled to name other students who are also permanently in wheelchairs. Piro said that although she knew of two other graduate students with physical disabilities, she has never spoken to them and does not know their names.

“Given all the other groups that exist and demand being noticed and having a voice on campus,” said Loughran, referencing the different cultural and minority groups on campus, “in that sense, we are one group that obviously doesn’t exist.”

Piro explained that disability is not a priority when one considers the word “diversity.”

Loughran added that while he personally does not need a specific group for people with physical disabilities, he does think it is important that a community of that nature exists.

Furthermore, when compared to other universities with historic campuses, Princeton is especially lacking in its transit services for the physically disabled.

Both Yale and Harvard offer vans for physically-disabled community members, according to their websites, while Princeton does not have a designated transit service for physically-disabled community members.

For instance, Yale offers a Special Services Van, which transports physically disabled students and faculty. The service runs 24 hours a day, Monday through Friday, and on Saturday and Sunday from 6 p.m. to 7:30 a.m. Passengers are picked up upon request.

Similarly, Harvard offers a Daytime Van Service, which is designated for students and faculty with physical impairments, and runs from 8 a.m. until 7 p.m. Monday through Friday, and 12:30 p.m. to 7 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. Harvard’s Evening Van, which is not designated specifically for physically-disabled community members, runs every night from 7 p.m. to 3 a.m.

Piro, who graduated from Harvard in 2014 with a degree in history, often used Harvard’s Evening Van and said that Harvard’s shuttle service ran more frequently than does Princeton’s TigerTransit.

Although the University offers 12 different buses through the TigerTransit shuttle system — as well as late-night buses such as On-Demand Bus and the UMatter Bus — according to the Transportation & Parking Services homepage, there is not a bus that operates 24 hours.

Erickson wrote in an email that all TigerTransit vehicles are ADA compliant and fully accessible.

Hess described the one time she used TigerTransit to go to Target as a “positive experience,” although she remarked that the Coach bus driver who took her and other students to see “Frozen” through Butler College did not know how to operate the wheelchair lift.

Naomi Hess pictured in a courtyard at Butler College, where she lives.

Photo Credit: Jon Ort / The Daily Princetonian

Harvard’s vans would also wait for students, explained Piro. At Princeton, she recalls previously racing across the sidewalk in front of Robertson Hall to catch a TigerTransit shuttle that departed early and falling out of her wheelchair due to uneven asphalt. The uneven asphalt was fixed by ODS the following day, and the shuttles ran on time more often after the incident, according to Piro, but there was still no bus designated for people with disabilities or a 24-hour bus.

When Piro requested that Princeton adopt Harvard’s Daytime van service, ODS raised the issue of cost, and the discussion lulled.

In an article Piro published for Inside Higher Ed in 2017, she explained that although institutions of higher education are legally required by the ADA to accommodate students with disabilities, college administrations can often get away with their responsibilities because of the act’s vague wording, such as the provision of “reasonable” accommodations.

The word “reasonable” is up for interpretation, said Piro.

“If it were up to me, every university would have van service and rooms with wheelchair access,” said Piro.

A problem on the Street: eating clubs’ lack of full accessibility

The issue of accessibility extends to the University’s eating clubs.

Although Loughran said that his experiences with ODS services are satisfactory, his biggest concern is exclusion from social life on campus; many eating clubs and dorms are not fully accessible.

According to former ICC Chair Paynter, only Cottage Club, Tiger Inn, and Ivy Club are fully wheelchair-accessible. Cannon Dial Elm Club, Tower Club, Cap & Gown Club, Colonial Club, Terrace Club, Cloister Inn, and Quadrangle Club are partially accessible, while Charter Club is only accessible when the club sets up a ramp for special events.

When asked what extra accommodations besides building accessibility that Cap has made for students with physical disabilities, former President of Cap, RJ Hernandez ’19, responded, “That’s not something that I … have thought about as much as I should [have].”

Eating clubs, although not officially affiliated with the University, play a crucial role in students’ social lives: more than 70 percent of University upperclass-students eat their meals and socialize at eating clubs, according to their official website.

Even though there are some wheelchair-accessible eating clubs, many students with physical disabilities do not bicker or are not even aware that eating clubs are accessible.

Loughran believes that only two of the eleven eating clubs are fully wheelchair-accessible, and Hess also believes that most of the eating clubs are not wheelchair-friendly.

“I might go to more eating clubs, if they were accessible,” Loughran said.

Ever since Hernandez joined Cap in his sophomore spring, he only recalls one physically-disabled student, Loughran, bickering Cap of the 400 prospective members he has witnessed bicker.

“Initially, I was shocked that [Cap] was one of the only accessible eating clubs,” Loughran said.

Loughran originally put down Cap as his first choice. However, because he missed one of the bicker sessions for Cap, he joined Cannon instead. He explained that he had always considered bickering, since members of his family who are University alumni had bickered.

“Bickering wasn’t that scary to me,” said Loughran. “Eating clubs try to make it as accessible to me as possible. Bickering was a pretty good [experience] for me.”

Paynter explained that while the eating clubs do not currently have a unified response to the issue of accessibility, their future goal is to increase accessibility.

However, she pointed out that elevators for every club may not be realistic, since eating clubs try to keep membership dues as low as possible. She explained that, to pay for the renovations to include elevators within eating clubs, money would be taken away from scholarships, and more fundraising campaigns would have to be held. She did not give an estimate as to how much renovations would cost.

“Disability rights are the only rights where there is a price tag involved,” Piro noted.

Hernandez said that he hopes to encourage more students with physical disabilities to bicker by coordinating with ODS and to have a Cap representative reach out to students with physical disabilities.

“We are willing to embrace anyone,” said Hernandez.

Current ICC Chair Meghan Slattery ’20 wrote in an email to The Daily Princetonian that the clubs were working towards accessibility as one of a number of ways to make the clubs more inclusive.

“A primary goal of the ICC is to continue making the Street as accessible as possible for all students who want to be part of one of these communities,” Slattery wrote. “We are working towards accessibility in many dimensions — financial accessibility, being diverse and inclusive spaces, and physical access to the building — and plan to use this year to keep improving in all areas.”

Piro wrote in her 2017 article that it is time to remove the burden from students with disabilities and ensure that all colleges and universities accommodate their needs.

In the next 10 years, ODS hopes to increase the University’s awareness of ability and difference through its 2017 AccessAbility Center, according to Erickson.

“In conjunction with the AccessAbility Center and our student fellows, we hope to introduce an ally program for those who have disabilities,” Erickson said.

Perhaps in the next 10 years, the prospect of playing Cards Against Humanity in friends’ dorms won’t be off the table for students in wheelchairs.

This article was updated to include information about federal law giving students the choice to self-identify as having a disability.