A couple weeks ago, Operation Varsity Blues led to the indictment of 50 people, including parents, college coaches, and standardized test administrators, in a wide-ranging college admissions cheating and bribery scheme. The indicted included two famous actresses, the partner of a private equity firm, a partner at a top law firm, and many more.

This was the largest college admissions case ever prosecuted by the Department of Justice. As he announced the indictment, the U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts affirmed that “there can be no separate college admissions system for the wealthy.” But the truth is, one already exists. The bribery scandal is an extreme manifestation of an underlying reality: America’s education system is rife with inequality, where opportunity is largely defined by money and social capital.

The aspect of this case that is so infuriating to people is the fact that rich parents were able to literally buy their children spots at elite colleges, spots for which many other students work tirelessly over years, both inside and outside the classroom. But even if these families cut the line to get into schools, there are plenty of other ways to get ahead in the process, ways that are completely legal and widely accepted as part of the game of admissions.

As he proposed his scheme to potential parents, William Singer, the scam’s orchestrator, described a front door, a back door, and a side door for getting into elite schools. The front door was getting in on your own. The side door was his way of guaranteeing admission through cheating or bribery. But the back door, the legal ways of getting ahead, are what we really need to reconsider.

Take legacy admissions, for example. By favoring the children of alumni over other comparable students, colleges effectively create a system that perpetuates privilege, giving additional advantage to students already ahead. According to The Guardian, at Harvard over the past five years, the admission rate for legacy students was over 33 percent — five times higher than the rate for non-legacies; and at Princeton, it’s about four times higher. Historically, many students in the legacy pool have been wealthy and white, meaning that the weight given to this status has reinforced the very racial and socioeconomic structures that education purports to transcend.

Even for non-legacy students who come from wealthy families, there are numerous ways to get a leg up. College counseling, test preparation, and the money and time to participate in a myriad of extracurriculars enable students with privilege to put forth the most polished college application they can, while other students are locked out of such opportunities.

In my high school, it was the norm to pay thousands of dollars for test-prep classes, one-on-one tutoring, and practice tests. Many paid to take standardized tests multiple times to get their target score and committed hours to practice. Additionally, many students met with counselors who helped form a balanced list of schools to apply to, brainstormed and assisted with essays, and answered questions along the way, taking much of the mystery and mythology out of the application process. But not everyone can do that. The problem, then, is that when colleges reward the results of this investment over other measures of merit, students without access to these resources remain a step behind their peers, and consequently their opportunities are restricted.

And it’s not just the application process that is unfair. Long before the college admissions process even begins, children’s educational opportunities are determined by wealth. Because public schools are funded largely by local sources, geography defines opportunity. The majority of students in the United States attend schools that are racially homogenous, where students are either predominantly white or predominantly nonwhite; and, predominately, majority-nonwhite schools are under-resourced compared to majority-white ones.

A new study by the nonprofit EdBuild revealed vast disparities in educational opportunity. Due to a long history of residential segregation, one in five students lives in a school district that is at once poor and nonwhite. This affects the quality of education students get, as the study found that white school districts get $23 billion more in funding than nonwhite school districts. That means nonwhite students, from an early age, have less access to opportunities that would set them up to go on to elite universities. Public schools, which are supposed to be the great equalizer, a chance for every child to climb the ranks into prosperity, merely reproduce existing inequalities.

The chance to break out of this cycle proves difficult as well. There are elite private schools, if you have tens of thousands of dollars to spare, but even well-resourced public schools disadvantage underserved students.

Stuyvesant, one of the most prestigious public schools in New York City and the country, admitted just seven black students and 33 Hispanic students out of 895 available spots, though black and Hispanic students comprise 66 percent of the city’s public school system. The numbers were similarly disproportionate for New York City’s other elite public schools.

In Massachusetts, black and Hispanic students are similarly underrepresented in prestigious public schools compared to the broader public school system. Boston Latin’s student body is 8 percent black, while the Boston Public Schools system is 33 percent black. Acceptance to these prestigious public schools is determined based on entrance exams, creating the same issues of inequality we see in the college process. This means that, once again, access to opportunity depends on a student’s resources, not on their merit.

We like to think that education can level the playing field, that it can allow a student to overcome their current status and work their way up the socioeconomic ladder. When the college bribery scandal hits, we delight in the schadenfreude of watching rich people get their due, and we criticize the illegal shortcuts they took. But we should look harder at the system they skirted and evaluate whether it really lives up to the values we espouse.

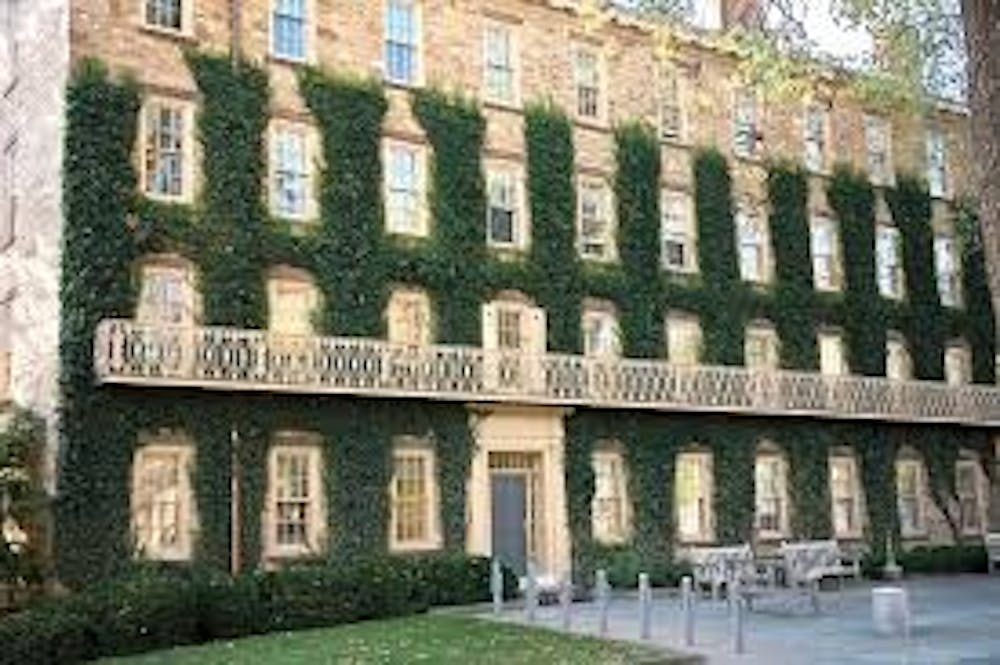

What we have now is far from a meritocracy. It’s no accident that more Princeton students come from the top 1 percent than the bottom 60 percent. This statistic is the logical result of the compounding inequities embedded in the education system. To cultivate a more diverse campus community, we must work to reverse these underlying problems.

Julia Chaffers is a first-year from Wellesley Hills, Mass. She can be reached at chaffers@princeton.edu.