As Princeton students, we are surrounded by noise. Whether it be unintelligible drunken shouts outside your window late at night or the patter of your roommate typing away, our lives are rarely quiet. Campus is abuzz with the cacophony of life: it is nearly impossible to sit beyond the range of some conversation or cars or distant organ music. As social creatures, we feel awkward sitting with someone and not maintaining a conversation. Silence somehow implies a lack of appreciation for the company of others and is perceived as rude. We are forced into prolonging a never-ending chatter which, for some reason, is apparently preferable to no conversation at all.

This never-ending soundtrack does not just resound in my interactions with others but also in my time alone. Reflecting on my own daily routine, I have realized the sheer ubiquity of noise and sound in my life. As soon as I set out for class, my headphones are in, blasting my morning soundtrack. Work is accompanied by music as well — seldom do I read a book or type an essay without Spotify setting the mood.

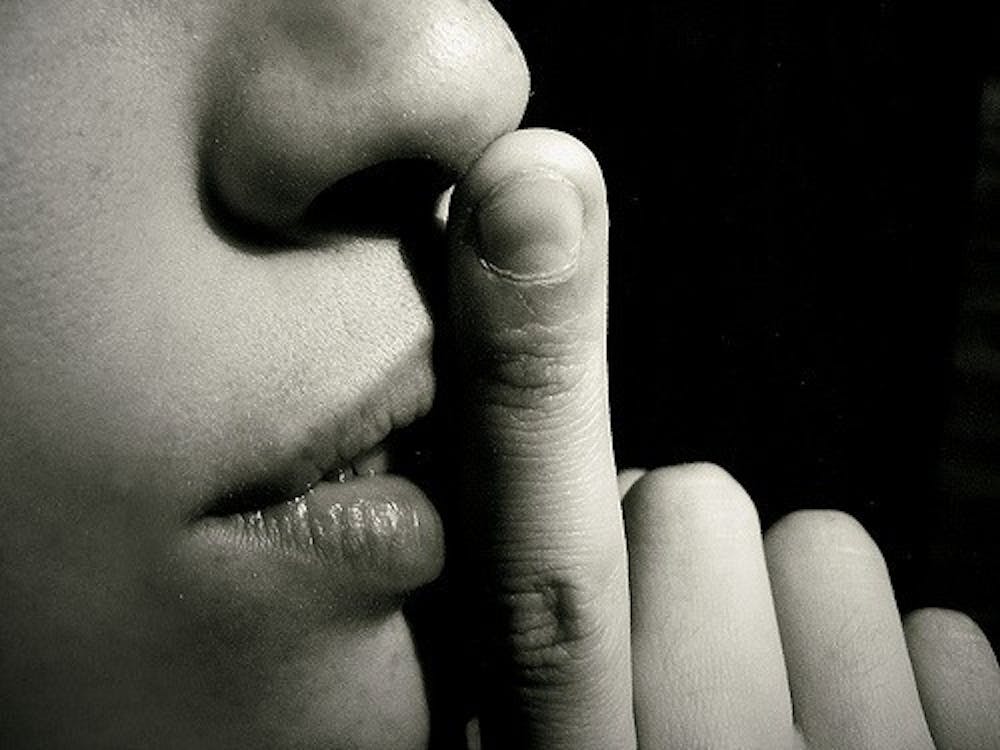

And even when I am sitting in silence, it feels taboo to do so idly. In other words, even if I am silent, my mind refuses to mirror that state. I feel almost exposed if I am seen doing nothing, so I, just as my peers, whip out my phone or a book or some other activity to escape the awkwardness of idle silence. Thus, refraining from conversation just pushes us towards a different activity, giving us the appearance of being “busy.”

Silence makes us twitch — why? Perhaps it’s because silence portrays us as unsociable or snobbish. This is why we turn to our phones or other personal distractions: if we appear “busy,” we have a more acceptable reason not to engage in conversation, since pulling out a phone has become an implicit signal that we wish to be left alone. While using a device in the presence of another person may seem rude, it feels considerably less uncomfortable than sitting in silence.

Or perhaps silence is uneasy because the noise of our lives distracts us from contemplating our more deeply-rooted anxieties and fears. For example, the one time of day where I am truly alone with my thoughts is when I go to bed. And, as soon as my head hits the pillow, repressed emotion and genuine reflection begin to swirl in my head. It’s as if, with my phone, friends, and music no longer a distraction, my mind can finally focus on subconscious and more raw thoughts. This is not a bad thing. Letting my mind wander and mull over various elements in my life helps me reconnect with myself and become more in tune with how I am feeling and how I see the future. Rather than keeping those anxieties pent up, contemplating them can provide release.

We shouldn’t shun silence as we do. According to writer Carolyn Gregoire in her article “Why Silence Is So Good for Your Brain,” loud or persistent noise “raise[s] stress levels by activating the brain’s amygdala and causing the release of the stress hormone cortisol.” In contrast, silence transforms our minds. Not only does it rejuvenate the brain itself, it relieves the stress and other tension accumulating in our lives. Blocking time — if even a few minutes — to exist in absolute silence, letting our minds wander or rest devoid of thought, is crucial to maintaining mental health. These few minutes, according to Gregoire, are more effective in lowering blood pressure than soothing music or other relaxing activities.

Conversely, there is a time and place for silence; we cannot always sit in silence and refuse conversation or human interaction. In addition to silence, we also shirk from uncomfortable dialogues with new people, whether that be sitting in a lecture or riding on a bus. The quest for silence should be one of moderation, since isolation is not the goal. At times, uncomfortable conversation is important as well, and it sparks personal growth, according to Sujan Patel in his article “Why Feeling Uncomfortable is the Key to Success.” The safety we find in routine is detrimental to our progress. Therefore, it is crucial to put ourselves into new situations since the failure to do so actually “dull[s] our sensitivities.” Silence and the reflection it engenders, in combination with forcing ourselves to be outgoing, are the path to optimal personal growth.

Thus, in the tumult of Princeton, your study break should not always be spent chatting with friends or seeing that a cappella concert. Instead, it is more worthwhile to find a place, whether your room or a secluded spot on campus, to sit and do absolutely nothing. Encourage your friends as well, so that more people are inclined to break that taboo precluding us from embracing silence. It may just be key to thriving during your time at Princeton.

Emma Treadway is a first-year from Amelia, Ohio. She can be reached at emmalt@princeton.edu.