I

“Enslaved African Americans built the modern United States, and indeed the entire modern world, in ways both obvious and hidden.”

― Edward E. Baptist, “The Half Has Never Been Told”

When we accept that prestigious offer of admission from Princeton University, some small part of us becomes part of the great history of Princeton ― and so some part of us becomes shackled, forever, to the stains of slavery, Jim Crow, and continued racism. Just as the United States and white Americans themselves are bound, morally, to offer reparations to African-Americans, so too is the institution of Princeton University. Because of the University’s complicity in slavery and structural racism, it has an ethical commitment to provide justice in the form of reparations to African-American students.

It is still somewhat controversial to remind ourselves that the United States was founded as a slaveholding nation, with slaveholding founders, with slavery in our Constitution. We are still haunted by this past.

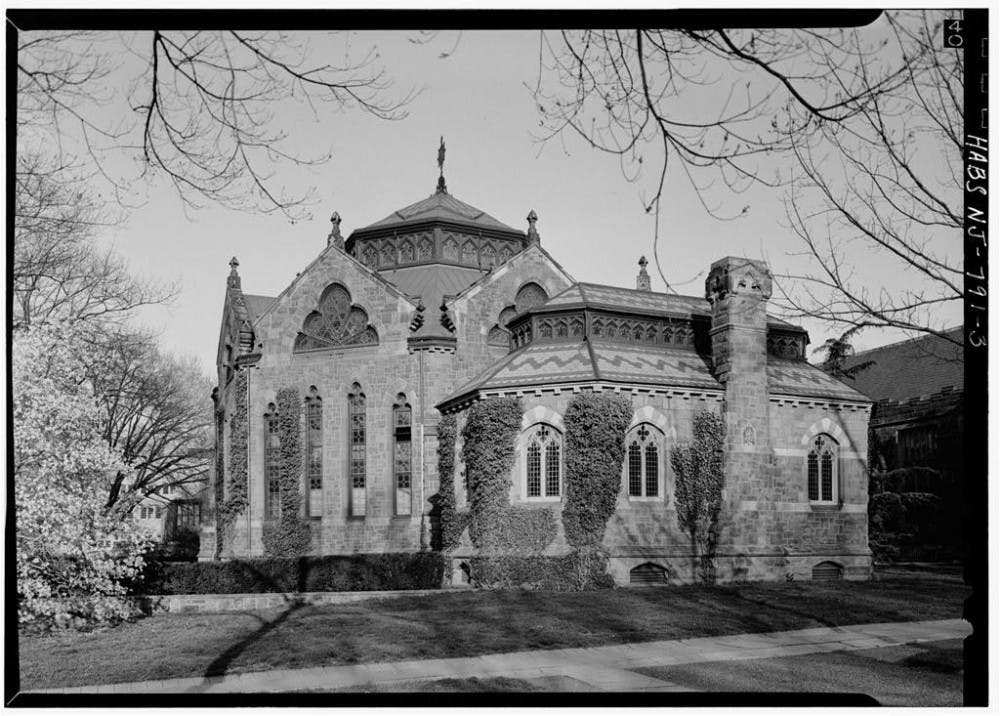

But to focus on the “nation as a whole” is to miss our own history, right here on campus. Princeton, of course, was not above holding slaves. Thanks to the publication last summer of the “Princeton & Slavery” project, Princeton has put together a tally list of its own particular crimes. The first nine Princeton presidents held slaves, as did a majority of our founding trustees. More Princetonians fought for the Confederacy than the Union. Princeton held slave auctions on its own grounds. Professors owned slaves ― some endowed professorships still honor men who came into their fortunes through slavery (Ewing, Dod, McCormick, Madison) ― and donations were financed from slave sales. Why would any of our professors, experts in their fields, want to be associated with these names? Then there are the sales themselves. How much of our mighty endowment, then, is soiled with that blood capital ― as interest and prestige accumulate year over year over year?

Princeton has always been the most conservative and “southern” Ivy League school. By the way, that is not my own perception ― in a letter to W.E.B Du Bois, a Princeton University administrator argued that “we have never had any colored students here, though there is nothing in the University statutes to prevent their admission. It is possible, however, in our proximity to the South and the large number of Southern students here, that Negro students would find Princeton less comfortable than some other institutions.”

Institutional prejudice did not end with our vaunted Woodrow. Yes, southern enrollment, which had been low after the Civil War, bounced back under his tenure, but Princeton remained white. The first African American to graduate from the University in peacetime was in 1951. Some might argue that Princeton has changed ― we no longer have slaves, nor do we prevent African Americans from entering the FitzRandolph Gate. By excluding African Americans over many generations, it left African Americans unable to access the capital, prestige, and resources that white students were able to have. While Princeton opened doors for white students, the FitzRandolph Gate stayed barred for blacks. And as we understand more deeply the cost of “dream hoarding” ― the upper-middle class’s stranglehold on chance ― does Princeton not foot some of this cost too?

II

“White America was ready to demand that the Negro should be spared the lash of brutality and coarse degradation, but it had never been truly committed to helping him out of poverty, exploitation or all forms of discrimination.”

― Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., “Where Do We Go From Here?”

Princeton undergraduates, because of their voluntary enrollment at Princeton, are complicit. Hence, we are all obligated to the University to honor its own obligations. “But I’m not guilty,” you might say. And the response to that is simple enough ― I am not arguing for individual Princeton undergraduates to provide reparations (though many of us likely ought to), I am arguing for Princeton University, as an institution, to right its wrongs. We, as undergraduates who voluntarily accepted Princeton’s offer of admission, should be bound by its obligations much as we are bound by many other obligations imposed on us once we agree to matriculate ― to write a thesis, to take so many classes a semester, to go on Outdoor Action, to stay out of disciplinary or academic trouble. We all accept admission on the understanding that there are obligations.

And the University, in its own capacity, has done wrong — and not wrong once, but wrong for generations. Any one undergraduate’s guilt or lack thereof is inconsequential. The University must atone for its wrongs. Princeton University is wealthy ― almost incomparably so. And yes, a certain amount of that wealth should be set aside for financial reparations to African Americans. But what Princeton could do that no other institution could do is use the resource that is most valuable and most irreplaceable ― its students and faculty. Princeton should require all students to contribute to the wellbeing of communities that it has almost certainly harmed throughout the years ― in particular, communities of color.

Princetonians ― the collected assemblage of confident, competent individuals ― have an unparalleled pedigree and skill set that makes us and our intelligence far more valuable than even the billions in our stock market portfolio. Throwing money at problems is great, but throwing skilled human capital is even better. This is our opportunity to liaise with those organizations on the ground, to learn from them and assist them in some substantial capacity. Princeton produces a bevy of skilled students ― engineers, statisticians, writers, artists ― that would be useful to almost any organization. Why does Princeton not provide those students the means to do the good work enshrined in our motto ― In the Nation’s Service and the Service of Humanity? Instead, the University seems more interested in ensuring Wall Street’s continued access to the best and brightest. But Princeton owes Wall Street nothing ― it owes those that it has benefited from plundering.

I cannot think that what has been done so far is anywhere near enough. Naming an administrative building after Toni Morrison is not the same as renaming the Wilson School. Tour stickers around campus are insufficient. Increasing diversity is not the same as reparative admissions policies ― for the Class of 2022 , African Americans make up only 8 percent ― roughly the same amount as the Classes of 2021, 2020, and my own Class of 2019. Yet African Americans are 13.4 percent of the U.S population. If reparations means giving more now to make up for less previously, we are failing dramatically.

As for all concrete proposals, I can’t confess to knowing exactly how Princeton should go about reparations. And ultimately, it is not my place to. I have no interest in falling into the neoliberal “white savior” trap. Perhaps the best way, as professor Avery Kolers at the University of Louisville suggests, is for Princeton to make available money and resources (credit hours, paid faculty and staff time, etc.) available to African American students, alumni, and target New Jersey organizations, who then have the final say on how those resources could be be used to make reparations. By being judges on competitive project boards or in some other way that ensures Princeton’s reparations are not imposed from the top-down, we could actively take into account the voices and perspectives of those the reparations are meant to aid.

III

“Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy. Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole.”

― Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations”

Having done wrong, what compels us to reparations? First, an appeal to common decency. When we do wrong, we are often expected or encouraged, whether by others or our own conscience, to do right by those we have done wrong. Even in the simple case of insulting someone, we can see that as an example of wrongfully taking status or dignity from that other person. An apology is the reparation. The ravages of slavery and the inequities of racism are far worse ― should not the reparations, then, be proportional to the harms done? Second, as John Locke points out, when someone does something wrong to another human, they violate that human’s status and dignity as an equal and as an important individual worthy of certain fundamental, natural rights. This should be familiar to any American: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

Reparations are a great divider. More than any other article, I know this one may have the greatest potential for controversy. Some part of me wishes I could hold my tongue. But it is better to speak the honest truth ― that you know which is right ― than the truth most palatable. Princeton — despite having bravely acknowledged its past failings ― has not done enough to make up for them.

In terms of symbolic reparations (names on buildings), or in terms of financial reparations (donations and financial aid), or in terms of reparations of human capital (volunteerism and affirmative action), Princeton has something to give. If white America owes black America, then so too does Princeton University have its own debt to pay.

Ryan Born ’19 is a senior columnist at The Daily Princetonian and a philosophy concentrator from Washington Township, Mich. He can be reached at rcborn@princeton.edu.

This is part of a recurring weekly column on politics and pedagogy at Princeton and abroad. Professor Avery Kolers (University of Louisville) contributed editing.