Bob Moses started his talk yesterday by asking the audience to say the words of the Preamble of the U.S. Constitution with him.

“I’m going to ask you to think about the Preamble, and whether you can own it,” Moses said.

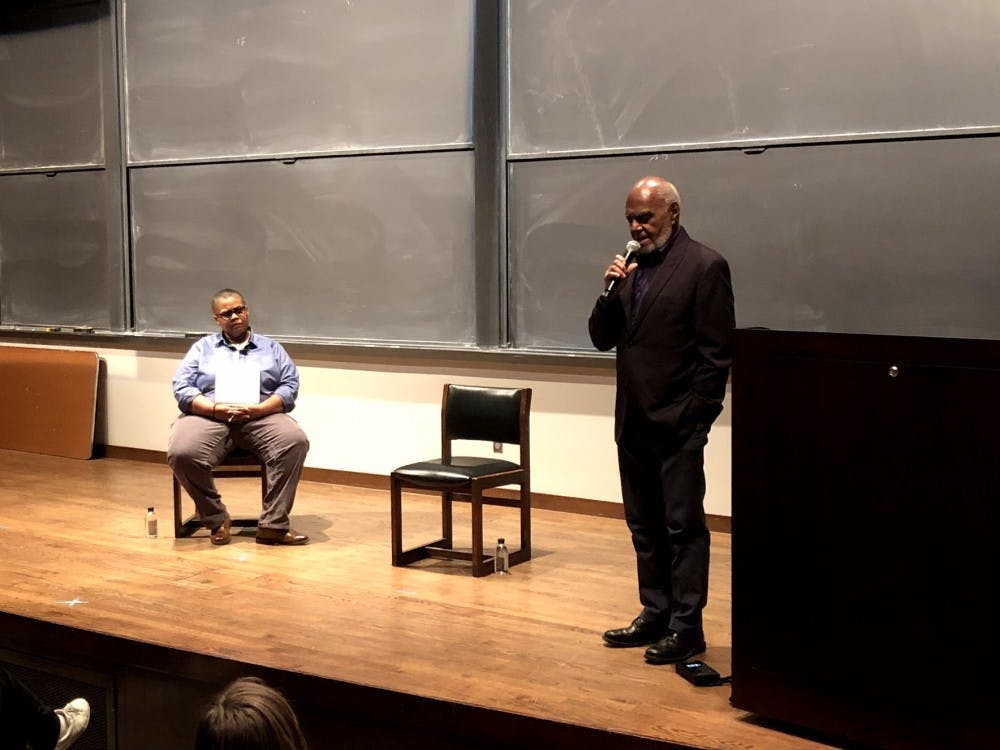

Moses is an educator and activist who was involved in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, voter registration in Mississippi during the Civil Rights Movement, and improving minority education. In 1982, he received a MacArthur Fellowship, which he used to create the Algebra Project, a mathematics literacy effort targeting low-income students and students of color. Yesterday, he joined Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, assistant professor in the Department of African American Studies, to discuss the evolution of U.S. racial justice political organizing.

Moses pointed out that the Preamble uses an active verb in the present tense: “Do ordain and establish.”

“It says in effect that there is a class of constitutional people who own the Constitution,” he said. “Nowhere in the text does it tell you who the ‘we’ is.”

To think the constitutional meaning is solely in the written text is ridiculous, according to Moses.

“What does it mean to be a constitutional person in this country?” he asked the audience. “What does it mean to be a constitutional person?”

Part of that answer can be found in Article Four, Section Two, Clause Three — the Fugitive Slave Clause, which required that slaves who fled to another state to be returned to the owner in the original state. That clause, explained Moses, identified another class: constitutional property, Africans.

The clause outlined the obligation of the federal government to return “any constitutional property that decides to leave the constitutional person,” he said.

“Right there in the Constitution, in the very beginning, is the basic conundrum of the country. Where are we now? What has happened in our constitutional era?” Moses asked.

In the first constitutional era, Africans were struggling to become members of the Preamble, according to Moses.

After the Civil War, when the country entered Reconstruction, Moses said there was a lurch forward. The second lurch came a century later, with the Civil Rights movement.

In voting, housing, and public transportation, the question of the meaning of being a citizen of this country was being raised, said Moses.

“The only area is public accommodations,” he continued. “The country agrees that we all have constitutional status in the public sphere of this country. We can’t belittle that. The struggle goes on.”

Asked about the legacy of the Civil Rights movement, Moses responded that first it was portrayed in terms of Martin Luther King Jr.

Moses pointed out that using King as the face of the Civil Rights movement can be discouraging, because young people do not think they can be like King. Moses prefers a description of the movement that gives people an easier entry point.

“When you portray the movement in terms of King, there’s no context for the movement. The better metaphor there is that King is a huge tidal wave coming out of an ocean. What is that ocean, and how did it create that tidal wave?” Moses asked.

“You have to understand the constitutional eras of the country, when it has lurched forward and back,” Moses said.

“The last presidential election alerted everyone that the country’s lurching. The question was, which way?” Moses said.

Moses discussed his time as a civil rights leader in Mississippi, where he worked with the SNCC and helped organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which challenged the all-white Democratic Party delegates at a 1964 convention.

Before going down to Mississippi, Moses saw pictures of the young people there in The New York Times.

“They looked like I felt,” he said. “One thing led to another.”

He compared organizing to low-grade guerrilla warfare.

“You were exposed and possibly opened to some danger,” he said, adding that the danger came from different groups: the highway patrols, local sheriffs, and other citizens.

What is difficult, according to Moses, is understanding what an organizer’s work is: becoming part of the community to organize around a particular issue and getting the community to figure out that it has a voice and role to play.

He added that he needed to convince black citizens that voting is worth personal danger. Additionally, he needed to earn the respect of the Justice Department because they were the ones who held the keys to the vote.

“But they put in [the 1957 Civil Rights Act] that you couldn’t arrest people for trying to vote. For them to decide that, we had to discipline ourselves and just do voter registration. So whenever we got locked up, the presumption was it was voter registration,” he said.

Discussing his work with MFDP, Moses said he learned that the key to unlocking Mississippi’s political and social caste system was the Democratic Party’s structure.

“White people have switched from Democrats to Republicans,” he said, adding that the question of being a Democrat or Republican hinged on white supremacy.

“Along comes Trump. What’s been happening all along, but hasn’t been a part of the national politics is out in the open. So here we are, and where are we going?”

Moses was critical of the mass incarceration of black people and police shootings. In particular, he noted the topical issue of gun rights.

“The issue of the Second Amendment has to do with black people,” he said.

Asked about the Black Lives Matter movement, Moses said that one problem is that it is coming into being at a time when people leapt overnight into national consciousness.

Moses said that education should be an organizing tool for young people today, citing a 1971 Supreme Court case that set the precedent for states to be the judge of educational quality.

“You can’t come to courts for equity relief because there’s no constitutional right to education. Now the issue is fought state by state,” he said, adding that the states’ constitutions are failing to do the job.

Moses called the current educational system “sharecropper education.”

“The whole country is getting an education for the 20th century and factory work when what they need is education for 21st century and information technology work,” he said.

“Unless we figure it out, we’re going to lurch in the other direction.”

The talk, “SNCC to BLM: Robert Moses Discusses the Evolution of Racial Justice Organizing in the U.S.,” took place at 4 p.m. on April 8, 2018, in McCormick 101. The event was cosponsored by the Department of African American Studies and the Pace Center for Civic Engagement, as part of the Organizing Praxis Lab’s public speaker series. OPL, started after President Donald Trump was elected, seeks to educate activists on how to organize through a year-long training program, sponsored by the Pace Center and the University Center for Human Values.