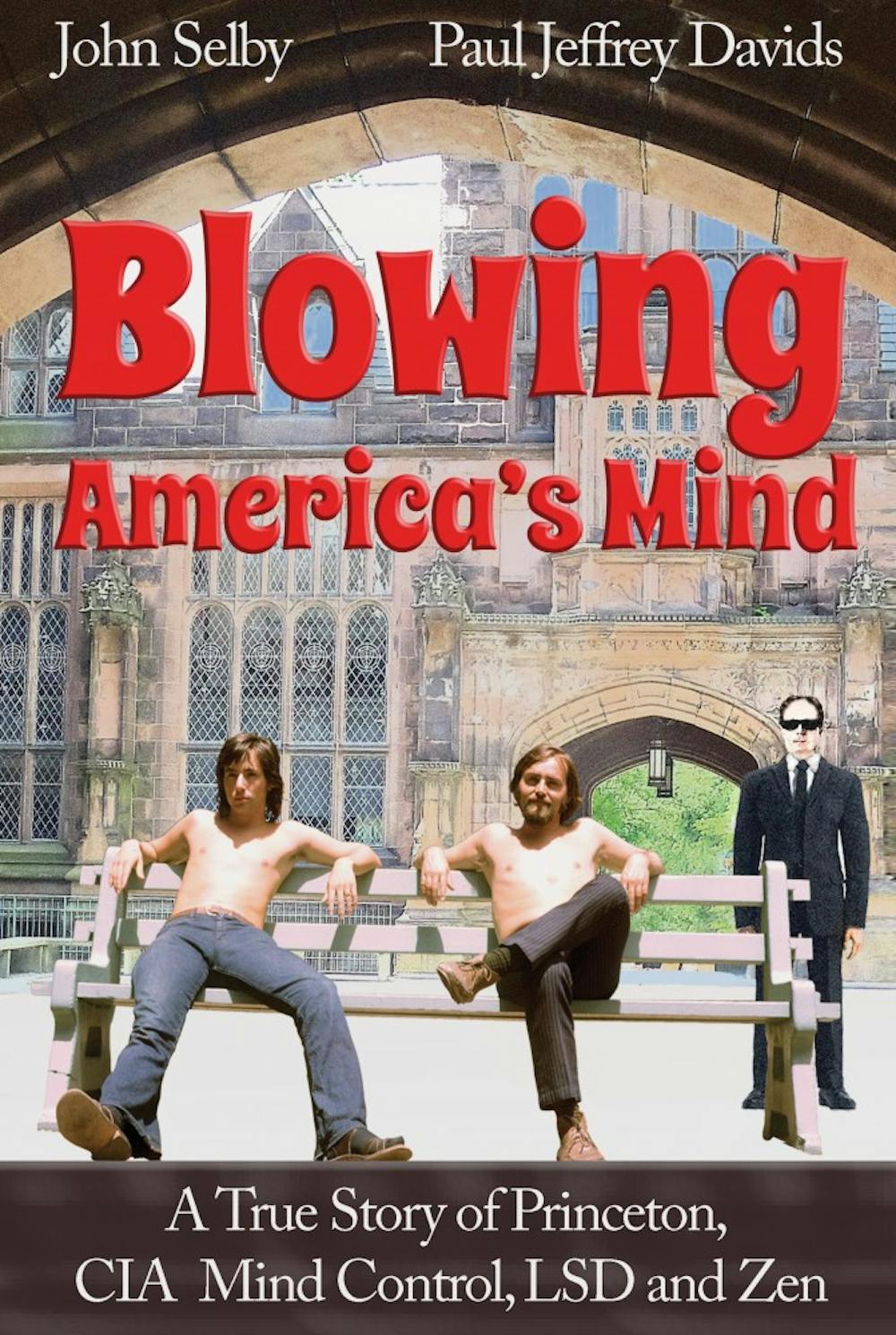

A new book, “Blowing America’s Mind: A True Story of Princeton, CIA Mind Control, LSD and Zen,” documents the experiences of two University alumni who were subjects in LSD and hypnosis experiments at the now-defunct New Jersey Neuro-Psychiatric Institute’s Bureau of Research.

Under the research objectives of Dr. Humphry Osmond, who coined the word “psychedelic” and guided Aldous Huxley on the mescaline trip featured in “The Doors of Perception,” John Selby ’68 and Paul Jeffrey Davids ’69 were hypnotized and given LSD to explore altered states of consciousness.

In 1977, news broke of Project MKUltra, a program of experiments on human subjects undertaken by the Central Intelligence Agency to develop drugs and procedures for interrogations and torture. The program, which started in the early 1950s and ended in 1973, used front organizations, such as colleges, hospitals, and prisons, to conduct the experiments while hiding their connection with the CIA.

“We knew we had volunteered for hypnosis and LSD research,” said Davids, “but the fact that it was being funded by the CIA and that the doctors we trusted … were working for the CIA — we didn’t know about [until] 10 years later, when MKUltra was exposed.”

On Aug. 3, 1977, former CIA Director Stansfield Turner confirmed that “86 institutions were involved” in “149 separate research projects.” Princeton and Columbia were two of these institutions, notified personally by the CIA in a set of letters admitting that Princeton students “had apparently been involved in a phase of CIA testing between 1953 and 1964.”

According to a 1977 article in the Los Angeles Times, CIA experimentation with LSD began “out of concern in the 1950s that the Russians and the Chinese had developed effective techniques in mind control,” resulting in fear that “American prisoners of war or American diplomats” would fall victim to these tactics.

A news release from the University Office of Communications on Sept. 1, 1977, provided further details about the experimentation, including that “CIA funds totaling $4,075 were paid in 1953 and 1958 for research by two individuals who were then affiliated with the University.” The release also refutes any claims that the “University as an institution was involved in this research.”

In email correspondences to former University President William Bowen on Aug. 31, 1977, former University Research Board chair Robert May confirmed that a chemistry department faculty member was paid $753 for “characterizing the alkaloids present in seeds of [Ipomoea] Sidaefolia Choisy” which are known to have “‘disorienting effects when ingested.’” May could not confirm “whether the chemistry was done in a Princeton laboratory or not.”

“I saw a notice up on the bulletin board in the [psychology] department when I was a junior,” said Selby. After completing a questionnaire and an interview with Dr. Bernard S. Aaronson, a hypnotist, Selby was signed off by the department to count his work at the Institute as course credit.

According to The New York Times, before the Institute existed, the first of three mental health facilities on the now-abandoned plot of land in Skillman, N.J., was open — the New Jersey State Village for Epileptics. This village was built in 1898 and was originally intended to be a “self-sustaining agrarian community” for epileptics to “live together in a wholesome environment” and “receive medical treatment” away from asylums and prisons.

In 1953, the village was turned into the New Jersey Neuro-Psychiatric Institute, a research and treatment center catered towards “alcoholics, drug addicts, emotionally disturbed children[,] and people with cerebral palsy.”

The Institute was remodeled a final time in 1983 and renamed the North Princeton Developmental Center, focusing primarily on “developmental disabilities, cerebral palsy[,] and other neurological disorders.” The center closed permanently in 1998 and was completely demolished by 2012.

“I learned about the Neuro-Psychiatric Institute’s hypnosis research from a poster on a kiosk on Nassau Street,” explained Davids. “It made it out that it would be research that could help you lose your inhibitions. The implication was that it might even improve your sex life.”

According to Davids, the all-male campus culture placed “enormous pressure on how [the students] would meet women,” and students would “have to go to lengths to meet girls and maintain relationships.”

The Institute presented its research as a study of meditative states and altered awareness. In reality, research subjects experienced “some of that,” according to Davids, but the research took an unexpected turn.

“It put us through some harrowing experiences, very deliberately because [the researchers] wanted to study our behavior and reactions under psychedelic drugs and/or deep hypnosis conditions in which our sense of reality was changed, sometimes in ways that would provoke temporary psychotic episodes … other times, a positive and more mind-expanding experience,” he said.

“Before 1966, you had people disseminating LSD everywhere,” explained Davids. Sandoz, a pharmaceutical company, produced the drug. In 1966, public funding was cut and LSD became harder to procure, an effect that “certainly has thwarted serious and vital scientific work,” as a Daily Princetonian reporter wrote in 1966.

Although LSD sources became scarce, the Institute continued to carry out the studies.

“From 1966 onward, they were ordered … to cease all LSD studies, and they therefore should have used hypnosis to induce similar states,” explained Selby. “But they didn’t. They kept using LSD.”

In 1967, Selby conducted a questionnaire survey of drug use among students. He found that 15 percent of undergraduates at the University experimented with marijuana, hashish, or LSD, and that two thirds of the users are on the Dean’s List, as The New York Times reported.

That same year, the Princeton University Student Committee on Mental Health, which Selby served on, released a pamphlet discussing the “social, medical, and legal aspects of psychedelic drug use, descriptions of a successful and unsuccessful trip, and clear definitions of drug-related terms.” Aimed towards dispelling “pretensions and moral judgments” about psychedelic drugs, the pamphlet was sold at the local town bookstore.

Robert Herbst ’69, an associate opinion editor for the ‘Prince,’ published a “critique of the drug report” and excoriated the lack of medical information in the pamphlet. Herbst claimed that “hardly any LSD is used and interest centers around marijuana and hashish” at the University, making the pamphlet’s legal and social sections obsolete for the majority of students.

Former University President Robert Goheen commended the efforts of those students who distributed the booklet, “Psychedelics and the College Student.” He said, however, that “what good it will do, I don’t have the vaguest idea in the world.”

Goheen asked to meet with Selby to better understand psychedelic use on campus.

“He was a very devout religious fellow,” said Selby, adding that the President was upset about the situation on campus. Selby met with President Goheen between eight to 10 more times, and Goheen became more involved, eventually sponsoring a forum on psychedelics, according to Selby.

Goheen even arranged for Selby to receive a diploma his senior year, when Selby and his pregnant wife fled for California one night after a bad encounter with the CIA. Selby met Alan Watts, a British philosopher who popularized Eastern philosophy in the West, at a seminary in San Francisco.

Davids and Selby recall the some troubling effects of the drug experimentation at the Institute.

When Davids began his time at the Institution as a research subject, Selby, then a research hypnotist, was assigned to him to train him to go into deep hypnotic states.

“At that time, [Selby] was undergoing a psychological crisis as a result of the deep hypnosis experiences he had been put through for over a year, in which there were hypnotic conditions that he was convinced were never erased. He felt he was still being manipulated by the doctors at the Institute,” explained Davids.

When Davids was in a trance, Selby had an out-of-body experience where he was hypnotically made to experience that he was a bird and flying away, according to Davids. Selby, convinced the doctors had never restored his memory of growing up on a cattle ranch in the West, went upstairs to confront Dr. Aaronson, who ended Selby’s panic by putting him into a trance.

Coming to the University, Selby had never even had a beer.

“I was an absolute straight, Republican, conservative, Presbyterian cowboy,” he said, adding that he was lonely and lost his freshman year.

His sophomore year, he was “pretty much an alcoholic.” Joining Tower Club, he had the opportunity to enter a stabilizing group, but felt he was still drinking too much.

“The main problem at Princeton, when I was there, was alcohol,” he added.

When he started at the Institute and was introduced to hashish, Selby stopped drinking. As he continued research at the Institute, he began using more psychedelics.

“I did get more and more weird … mostly from the LSD and research we were doing,” he said. “Dissociative disorder is what it would be called now.”

Selby looks back on his involvement with the CIA’s LSD experiments as rather traumatic, but emphasizes that he does not believe that the psychedelic drugs themselves were the cause of his distress.

“I wouldn’t blame the LSD for my freakout,” said Selby. “I would blame the Institute. But also just the fact that we were so frightened of getting caught, that made us paranoid. And when you take a psychedelic and you’re dealing with paranoia, it’s dangerous.”

“The process of writing the book was therapeutic,” said Davids, adding that it allow him to “break through some of the fog we’d been put in.”

Davids is an independent filmmaker and writer. He has written and directed several films and has written television episodes for the Transformers series as well as a spin-off of the Star Wars series.

Selby is a psychologist and author. He has written over two dozen self-help, spiritual-growth, business-success, and psychology books. Recently, he has written a book and accompanying mobile app, Mindfully High, to provide marijuana users with professional insight to guide their experience.