Beginning at 1:30 p.m. on Thursday, March 8, graduate students from multiple academic departments interrupted approximately eight classes on the third floor of East Pyne Hall to protest for International Women’s Day, which is March 8.

“It was seen as an interruption of the day-to-day comfortability that Princeton runs on,” said Verónica Carchedi, a graduate student in the Spanish and Portuguese department.

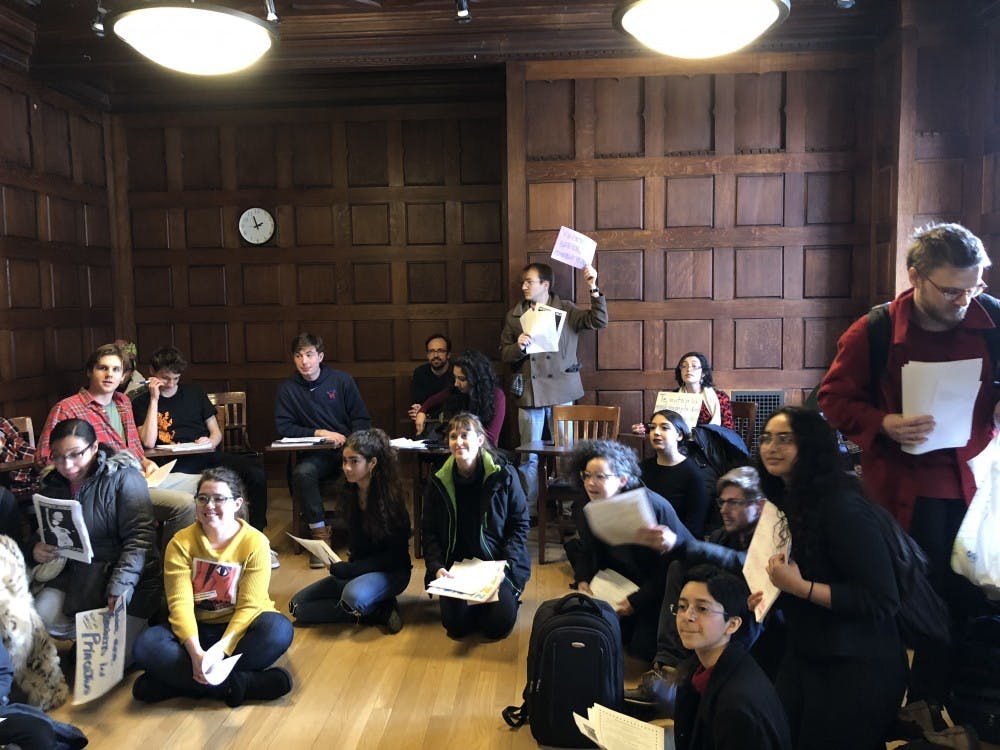

The plan was to occupy East Pyne. After the protesters entered the classroom, they read their reasons for striking from their “manifesto.” They also encouraged students to walk out and join them. Only one unnamed professor knew of their plans and walked out with the students.

“[We wanted] to interrupt the classrooms, not ask for permission just to get in,” explained Luisa Barraza Caballero, another graduate student in the Spanish and Portuguese department.

The protestors chose to begin their protest at East Pyne because for many of these students, it is the building where they study and attend seminars, according to Paulina Pineda Severiano, a graduate student in the comparative literature department. From East Pyne, the protest moved to and concluded at Frist Campus Center.

“We’re making an action here in Princeton where we live and work, so we could take part in the March 8 International Women’s Strike in this space without needing to go to New York or Philadelphia. We wanted something on campus and with the community we’re trying to build here,” said Sophia Nuñez, a third graduate student in the Spanish and Portuguese department.

The protesters said they wanted to raise a disruption in order to draw attention to issues that they believe are not being heard as loudly as they should be on campus.

“WE strike here because this is the space we work, study, live, feel . . . the place that wears us down,” a flyer that the protesters distributed said.

The same flyer gave specifics that caused the protesters to come together, noting that the students are tired of being “well-intentioned statistics in your white heterosexual and patriarchal University.” It said that the protesters are “[t]ired of theorizing the body while going three hours without a bathroom break” and even referenced Winter Storm Quinn.

“Who are those ‘essential laborers’ that had to come to work from other towns during the storm yesterday?” the flyer asked, referring to the essential personnel that had to work on campus the day of the storm.

In an interview with The Daily Princetonian, a number of protesters noted that students had different reactions to the interruption of their classes. Some laughed and gave looks. Some were reluctant on whether they should join the protest. But others stood up and walked in solidarity with the demonstrators.

“The point is that there are grounds for this to happen in Princeton,” said Carchedi, “and people are willing and excited about this kind of action.”

According to Carchedi, more people participated in the protest than expected. At least 30 people had protested, according to one estimate. The protest also lasted longer than they had thought. When the demonstration concluded at Frist, the protest had already gone on for roughly an hour.

The protesters had been concerned about these issues of feminism for a long time but only began planning the protest in the past week. They sent out an email this morning that called on students to protest with them.

A flyer obtained by the ‘Prince,’ which was sent via email, listed observations that participants made about the “patriarchal facts of our everyday university life” that spurred their decision to protest.

“The presence of female authors in the syllabi of the graduate courses at the Spanish and Portuguese department, except for those specifically «female-themed»,” wrote the flyer, “range from 0% to a maximum of 23%.”

Jannia Gómez, a fourth graduate student in the Spanish and Portuguese department, described the day’s protest as a “minga,” a word used by the indigenous people in Colombia to refer to “gathering” and “walking the word.”

“It’s more than enacting because it has to do with walking that path,” Gómez explained. “We were walking our thoughts, our spirits, our conversations, our crying.”