Since its origin in 2008, the Petey Greene Program has allowed Princeton students to tutor in a rather unique setting — prison.

The organization’s mission is rooted in criminal justice reform and focuses on “preparing volunteers, primarily college students, to provide free, quality tutoring and related programming to support the academic achievement of incarcerated people.” While the program consists of hundreds of volunteers from 32 universities, it began here at Princeton.

Executive director Jim Farrin ’58 recalled the day in 2007 when he got a call from an old classmate, Charlie Puttkammer ’58. “He [Puttkammer] said he wanted to start a program with Princeton students entering prisons to help incarcerated individuals.” Though Farrin, who was a businessman at the time, thought it was a great idea, he told Puttkammer that he was unfortunately too busy with his own business to be involved.

24 hours after this conversation, however, Farrin’s wife was attending the first reunion of the Princeton Theological Seminary where she happened to meet the chaplain supervisor at the Albert C. Wagner Youth Correctional Facility, the very place Puttkammer told Farrin he wanted to send Princeton students to volunteer. Seeing this as a “sign from above,” Farrin reassessed his initial response and circled back to Wagner to pursue the opportunity.

After going to the prison, Farrin decided to take the job, but one small detail still remained — what would the program be called?

“Jim, we’re gonna call it Petey Greene,” said Puttkammer, to which Farrin responded, “Charlie, I’m a marketing guy and if you call the program by a name like that, I’ll spend half my life explaining to people who Petey Greene is.”

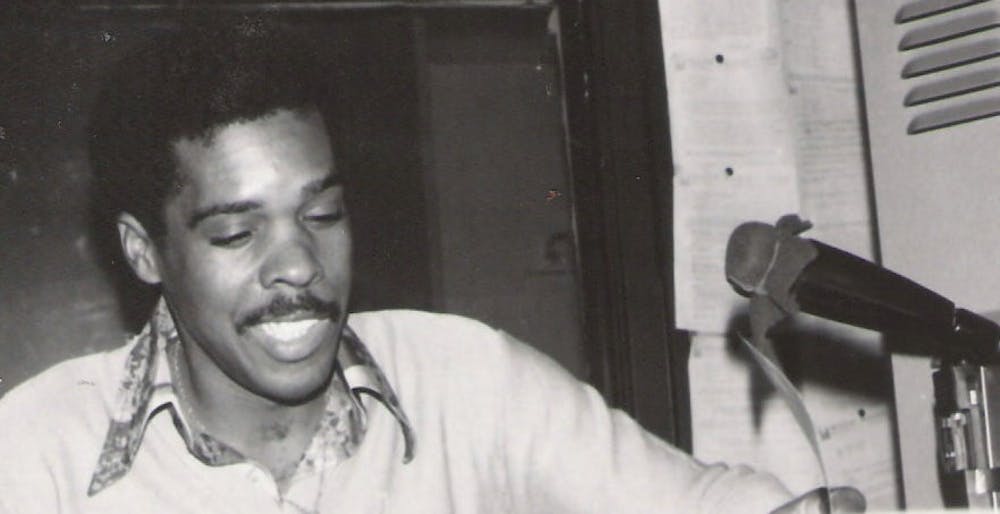

Ralph Waldo “Petey” Greene, Jr. was a formerly incarcerated individual who eventually became one of Washington D.C.’s most famous talk show hosts and media personalities. Puttkammer was a close friend of Greene and wanted to start the program in his honor.

Farrin finally conceded after Puttkammer promised the naming would be “the only direct order I’ll ever give you.” Eventually, Farrin found his way to the head of the Pace Center for Civic Engagement. However, when he proposed bringing the Petey Greene Program to campus, he was initially met with hesitation and told that Princeton students might be too busy to participate in this type of program. He walked away with just a couple of inserts in the newspaper. But, even with only a few inserts, Farrin received ten responses in one week.

After the first meeting in Frist, 25 students completed background checks so that they could start volunteering. The program took off and found incredible success. Farrin noted, “We surveyed our volunteers after the first semester and very surprisingly, they gave it a 4.75 out of 5.”

“The most common reactions were ‘I didn’t know this population existed,’ ‘This was my first time to help people’ and 'I want to go for all my time here.’”

Een Jabriel, a division manager of the program who was formerly incarcerated, noted the impact tutors have on their students: “You never know what kind of conversation you could have that could just spark something.”

Jabriel believes participation in programs like Petey Greene should be mandated for all college students so that they can gain a better understanding of the shortfalls of the criminal justice system. “I noticed that it broadens a lot of peoples’ perspectives, because we’re mostly limited to whatever the media shows us. And for the guys inside, I think the biggest thing they should be able to get out of it is realizing that there are people on the outside that don’t look at you the way the media wants them to. Then you don’t limit the way you behave. You don’t limit your possibilities.”

Today, due to both strong pushes by the program and intense volunteer enthusiasm, Petey Greene operates in 37 facilities and includes 715 volunteers from 32 universities across eightf states along the East Coast.

According to Program Director Jessica Weis, the process for expansion is initiated in two ways: either the program contacts a university if it seems like a good fit, or an eager student reaches out to Petey Greene, wanting to create a community on campus dedicated to criminal justice reform.

The same procedure is followed for bringing new correctional facilities to Petey Greene. However, Weis noted that recently, there has been an increased number of prisons seeking out the program themselves, as opposed to Petey Greene contacting them first. “When a prison comes to us, they want our services,” said Weis, when discussing how the organization is in increasing demand.

Looking to the future, Weis noted the importance of seeing results produced by the program: “We’re really trying to understand our outcomes and how our students are progressing as a result of our tutoring.” Farrin also expressed his desire to make Petey Greene a nation-wide organization.

Regardless of where Petey Greene goes, Princeton students have the privilege of saying that it all started right here. Farrin concluded by saying, “If you were to walk into my office on 9 Mercer Street, you would see a wall filled with testimonials from volunteers from Princeton and other schools who are thanking us for the opportunity. It’s the best job I’ve ever had because we’re helping people.”