“Fundamentally, our empathy or our compassion should not be based on the color of somebody’s skin, or the color of their passport,” Nicholas Kristof said on Tuesday to a packed room of eager town residents and students.

A New York Times columnist since 2001, Kristof joined the Times in 1984 to write about economics and presidential politics. He was awarded two Pulitzer Prizes for his reporting on the Tiananmen Square protests and the genocide in Darfur, respectively. Kristof has reported on six continents and traveled to more than 150 countries, including every country on the African continent, every Chinese province, and all of the main Japanese islands. Kristof, who grew up on a sheep and cherry farm in Oregon, has also lived through mobs, wars, malaria, and a plane crash. Since joining the Times, he has covered economics and presidential politics, then international relations topics as a foreign correspondent. AS of 2001 he has served as an op-ed columnist for the paper.

A proponent of web journalism, Kristof is also notable for being the first blogger for the Times. He is also active on multiple social media outlets, including Twitter (with over two million followers, more than any print journalist worldwide) and YouTube.

Much of Kristof's talk centered not on his journalism, however, but on the value of compassion and investment into the lives of others.

“Every now and then, in unpredictable ways, you take a risk on somebody, who maybe seems like they don’t deserve it, and yet it just multiplies and bears fruit and resonates through that person onto the lives of others in ways that one couldn’t have imagined,” Kristof said.

Helping abroad is often cost-effective, Kristof noted, but there are also important things to be done in our own communities. He added that there is sometimes a reluctance to engage in global aid efforts because it feels hopeless.

“One of the impediments to us is the idea that these problems are so vast that anything we do is just going to be a drop in the bucket,” Kristof said. He said that although it’s frustrating that we cannot solve problems in their entirety, drops in the bucket are important for those individuals whom we can help with education, healthcare, and other transformative interventions.

In terms of the role that the U.S. should play in humanitarian issues, Kristof noted that “the rest of the world has largely dropped off the U.S. radar.” He expressed his fear that because important issues are not being covered by journalists, these problems may not be addressed. Kristof noted in particular that he worries about attention on Syria, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

He encouraged audience members to use their own spotlights to keep these issues illuminated.

There has been a lot of innovation and creativity both at home and abroad, he said, describing a Father’s Day gift he received a few years ago from his children: a HeroRAT from the organization Apopo. The three-foot long rat is dispatched abroad and is trained to detect land mines and tuberculosis by smell.

However, he expressed frustration that even as we gain knowledge about what works and what can make a difference, we don’t tend to see investments corresponding to these things.

“The real challenge we face isn’t so much knowledge, it’s more political will,” he said. “In particular, it’s what might be called an empathy gap.” This empathy gap becomes particularly stark when it is compounded by divides of race, immigration status, or religion, he said, explaining that we have a human inclination to “otherize” people who are different from ourselves.

He said that if we confront these issues by engaging in difficult conversations, perhaps we can overcome our brains and the bias that is embedded in us, someday bridging these empathy gaps and building opportunity.

In America, the top 20 percent most affluent Americans donate less to charity as a percentage of income than do the poorest 20 percent of Americans, Kristof said, explaining that this may be due to insulation from need. He added that affluent people who live in more economically diverse communities are more generous than those who live in more economically homogeneous areas.

“Sometimes I think that liberals like myself talk too much about inequality, which tends to be a liberal word,” he said. “Maybe we should frame it more as opportunity.”

Speaking to issues of global and domestic poverty, Kristof gave the poignant example of the impact of investing in girls’ education, which he saw firsthand when he was in China in the 1990s. For him, it was a window into the way that educating girls could create a virtuous cycle of development that lifted up the whole community, benefiting men just as much as women.

“We talk about education, but in dealing with conflict and terrorism, we’ve overwhelmingly relied on the military toolbox, which has its place, but we have not relied much at all on the education toolbox and the women’s empowerment toolbox,” he said.

The power of education is something that extremists understand completely, he said. “They understand that the greatest threat to extremism is not necessarily a drone overhead, but it’s girls with schoolbooks,” Kristof noted. Terror attacks are probably more likely in tribal areas, where females are illiterate, than in Bangladesh, where girls are being educated, he added later.

“Educating girls isn’t just about creating economic opportunity or equality or social justice, but it’s also a security issue,” he said.

Meanwhile, Kristof pointed out that fewer than 10 percent of the world's population lives in poverty today. Hundreds of lives have also been saved since 1990, due to basic interventions such as vaccinations, anti-diarrheal treatments, and promotion of breastfeeding, all of which save lives cheaply.

“We cover planes that crash, not planes that take off,” he said, explaining that there tends to be negative bias in what we cover, leading us to miss the backdrop of progress that should be an inspiration to push harder.

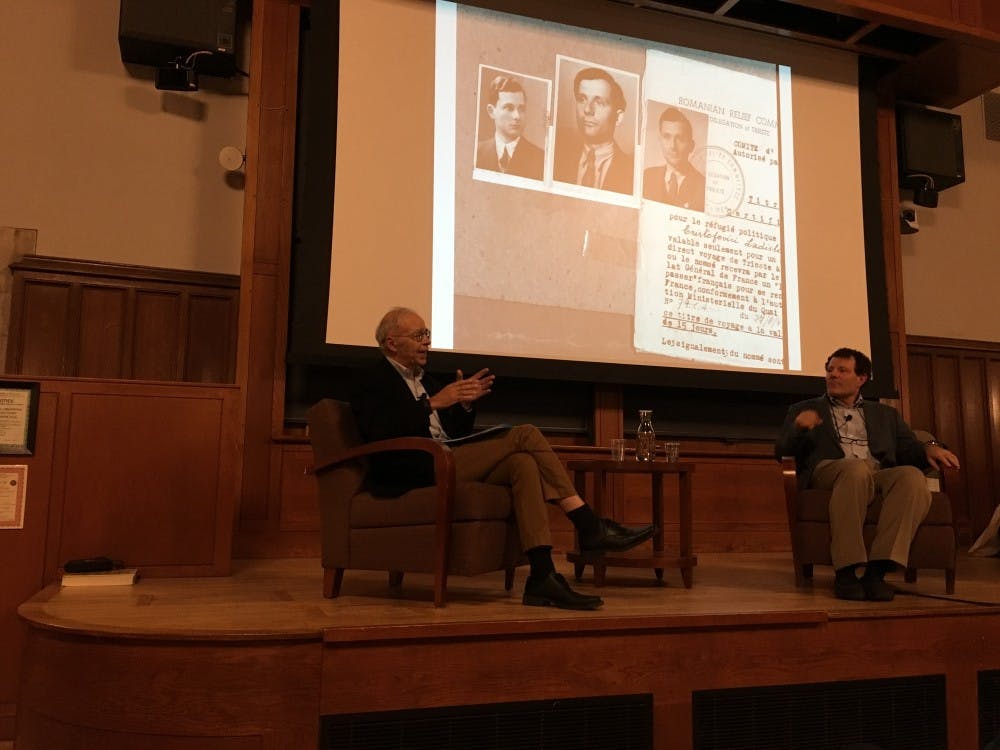

Peter Singer, professor of bioethics in the University’s Center for Human Values, moderated the Q&A session that followed Kristof's lecture.

Kristof began the Q&A by explaining that there is no perfect answer to what or where one should try to make a difference, because it ultimately reflects one’s own background and skillset. He stressed the importance of getting out of your comfort zone and encouraged young people to travel and interact with the larger world, whether through gap years or study abroad programs, to give people a sense of how the U.S. is perceived and how different people live.

Eric Gregory, professor of religion and chair of the Humanities Council at the University, posed a question about the balance and potential tension between charity and justice. In response, Kristof noted that it is striking that conservatives donate more to charity and volunteer more than liberals, but are reluctant to fund social support, while liberals are more likely to advocate for government programs than conservatives, but fail to appreciate what charity can do.

Students attending the talk were deeply impressed by Kristof’s work and impact on the world.

“The stories that he covers, very few people do these days.” Rohan Sinha ’19 said. “The importance of each of these stories is truly unquestionable. I mean, you name it: from North Korea to South Sudan, nobody else is covering that, nobody’s covering the Rohingyan Muslims in Myanmar,” he continued.

“He’s the one who’s actually going there,” Sinha added. “He’s down in the frontlines, trying to shake the world back into its conscience.”

Sarah Gordon ’20 attended the talk because of the connection she felt with Kristof as a fellow Oregonian and the inspiration she gained after reading his book “Half The Sky: From Oppression to Opportunity for Women Worldwide” in high school, which spurred her to engage in women’s rights and to be involved in organizations that Kristof has supported.

“He’s my celebrity crush,” she said.

Kristof and his wife Sheryl WuDunn, MPA ’88, have co-authored several best-selling books, such as "Half the Sky" and “A Path Appears: Transforming Lives, Creating Opportunity.”

The event, titled “Reporting in a World of Crisis,” was co-sponsored by the University Center for Human Values, the Humanities Council's Ferris Seminars in Journalism, and Princeton University Public Lectures. The talk took place at 6 p.m. in McCosh 50.